Borderzine is now accepting applications from journalism instructors at Hispanic serving institutions and Historically Black Colleges and Universities for full scholarships to attend its annual Dow Jones News Fund Multimedia Training Academy on the UT El Paso campus in El Paso, Texas. Journalism college instructors, please fill out the form below to apply for a fellowship to the 2024 Dow Jones News Fund Multimedia Training Academy, which runs from June 1-6. The Dow Jones News Fund provides funding for full scholarships to 10 journalism instructors from across the country to attend this fast-paced, hands-on multimedia training academy. The fellowship covers airfare (up to $600) to and from El Paso, lodging at the Hilton Garden Inn near campus with breakfast every day, four lunches and two dinners during the workshop. The deadline to apply is midnight on Friday, May 10.

El Paso’s untold stories emerge in new murals

|

Christin Apodaca believes she and other local artists have much in common.

“We all make things for our community and create spaces where you have something really fun to look at and think about,” she says. “And, you know, a lot of history is on the wall.”

It’s this multilayered history that seems to boost El Paso’s growing reputation as a city of murals.

Reverberations of musicians’ influence carry beyond the border

|

Border musicians rebel obstinately against the policies, politics, and razor wire seeking to divide this community.

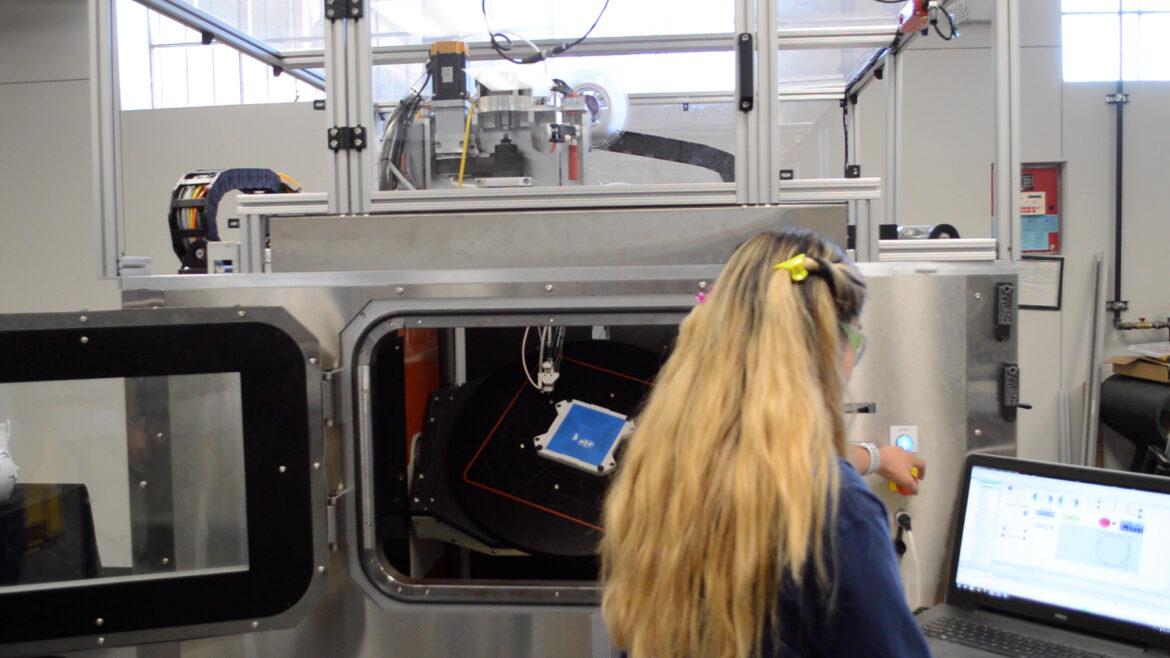

UTEP, El Paso Makes project power expansion in high-tech manufacturing on the border

|

With a fresh infusion of millions of federal, state and local dollars, El Paso’s growing aerospace and additive manufacturing industry is poised for explosive growth – and with it – thousands of high-paying jobs.

El Paso’s Mission Trail sees surge of growth and economic development

|

El Paso’s historic Mission Trail may be quiet on a Monday, but as the weekend approaches, traffic and visitors begin to stream into the small communities of San Elizario, Socorro and Ysleta. The trail is a 9-mile stretch of the Camino Real, the Spanish Royal Road built in 1598. Shops, museums and businesses once again teem with visitors along this section of the oldest European trade route in North America, which is once again seeing a resurgence in economic development.

Amid historic drought, El Paso’s river valley region welcomes arrival of seasonal water

|

In El Paso’s Lower Valley along the Rio Grande just north of the Mexico border, water is in short supply. While current drought levels are not as bad as they have been in previous years, area water officials, conservationists and residents remain nervous about water shortages that can affect crops and wildlife habitat.

Sacred Heart restoration reaffirms church’s role as safe haven for Segundo Barrio

|

Father Rafael Garcia, S.J., walks with measured steps to the altar to begin communion on Monday. The parishioners are a sparse but spirited group. Many committed congregants can’t make it these days because bus transportation has been limited since the pandemic.

Photojournalist has unique view of border life as a non-Spanish-speaking child of immigrants

|

Briana Sanchez frowns at the images on her computer screen.

“I need to add some happier photos in here,” she says. Sanchez, lead photojournalist at the El Paso Times, knows better than anyone the difficult times that the border has been through in the last two years. After spending eight years away, first in college in Georgia and Arizona and then working at newspapers in the Midwest, Sanchez returned home to El Paso in the spring of 2019.

“As soon as I moved back here, we had those patriots at the border, protecting the border on their own volition,” she says. “And then we had the ‘We Build the Wall’ people. And then we had the mass shooting.

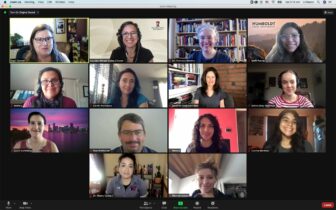

Dow Jones Multimedia Training Academy 2021 goes online with Navigating Multiple Worlds: Portraits of the children of immigrants

|

Two journalism students and nine journalism instructors from U.S. Hispanic Serving Institutions explored stories of children of immigrants for the 2021 Dow Jones News Fund Multimedia Training Academy June 5 – 10 hosted virtually by Borderzine through the University of Texas in El Paso.

Thanks to a grant provided by the Dow Jones News Fund, Borderzine organizes this annual training program geared to support multimedia journalism instructors who teach in institutions with a large minority population.

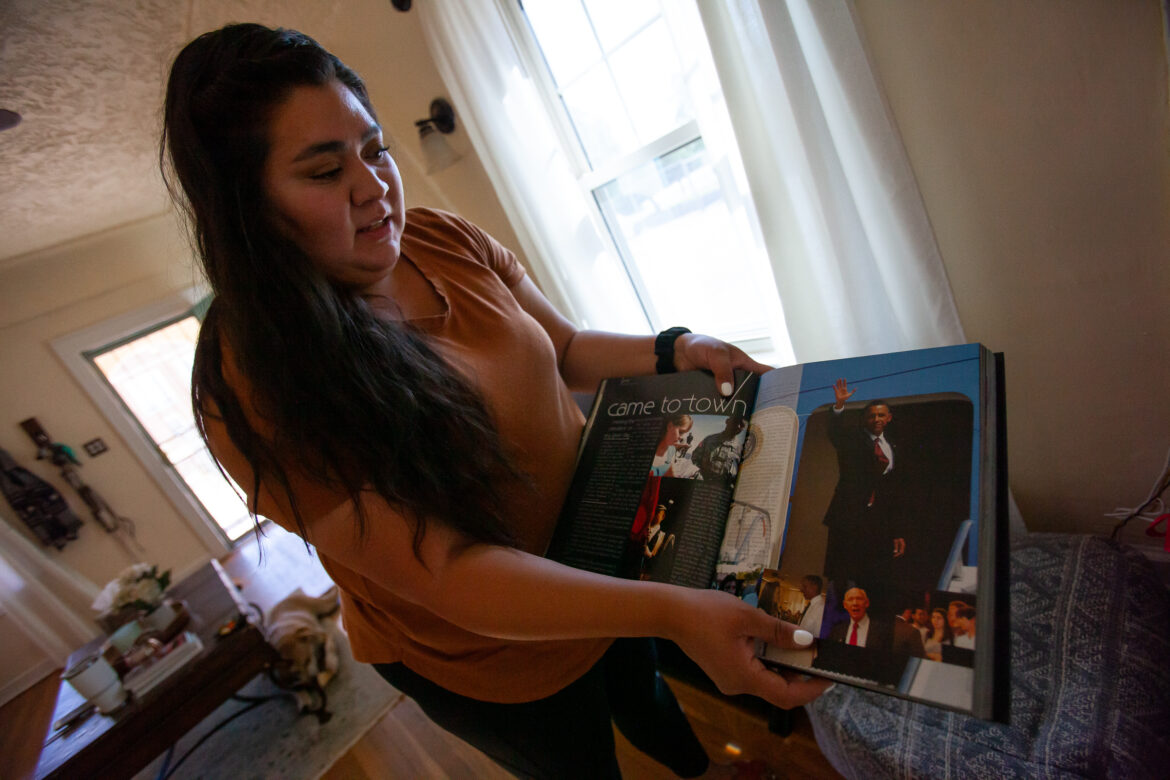

Changing times, support raise aspirations for youth in The Barrio in Amarillo

|

On the glass coffee table, with her favorite issues of the Golf Magazine, she finally finds the book.

“It focuses more on the now. Some people I recognize, some people I don’t”, said Maria Guerrero, whose dad immigrated from Mexico. “It gives you a start on the historical aspect of El Barrio.”

The Barrio, which in Spanish means neighborhood, was developed in Amarillo, Texas, to house railroad workers brought to the U.S. from Mexico. It is full of history, culture, and family stories.

“The focus was always the thought that we were going to grow up, finish school and get married and raise families,” Guerrero said. “So that kind of cut my education, higher education short”.

The pressure to marry came from her mother. The high school counselors didn’t help.

“I lacked that initial push,” she said.

Musician draws on diversity of influences as a teacher, performer and composer

|

Christian Cruz, 30, is a musician, composer, and second-generation American who lives in Los Angeles. When not teaching guitar lessons or playing gigs, Cruz, who holds two master’s degrees in the field (USC and Fresno State), finds his talents best satisfied with project-based music composition. He also looks forward to teaching this fall with Lead Guitar in Los Angeles, a non-profit that takes music education into schools with low access to the arts. He took some time to tell part of his story to Borderzine from the home base of his “Caucasian family” in Denair, a small town in California’s Central Valley. Cruz was visiting, along with his spouse and fellow musician, Erin Young, who he met in USC’s music program.

Gardening keeps family traditions alive across generations

|

Cindy Vasquez is a second-generation Mexican American who lives in Oakdale, California. She graduated from Enochs High School in 2019. Her grandparents migrated to the U.S. from Mexico, when her mother was a young child. Her grandfather, Paul Velasco, learned to garden from his father and continued after the family moved to California. Cindy Vasquez embraces her life of rooted tradition and culture.

Thanks to lessons learned in a family of nurses, 2nd generation Filipina builds a career in art

|

When Noelle Mongcopa was a young girl, she felt compelled to draw and create art, spending hours copying her favorite images of Dragon Ball Z and Pokemon characters. Today, she has channeled her creative force into her career as a toy designer and product manager. However, the choice to pursue an artistic career wasn’t an obvious one. Mongcopa grew up in a family of medical professionals, where becoming a nurse was not only a family tradition, but also considered a responsible financial decision. Both her mother and her father immigrated to the United States from the Philippines in search of more professional opportunities, and worked as nurses for many years.

Daughter of Salvadoran immigrants cultivates inclusive space in rural white community

|

As the oldest daughter of immigrants from El Salvador, Karina Ramos-Villalobos’ job as a child was to translate and guide her parents through the language barrier they faced in their adopted country.

Photojournalist has unique view of border life as a non-Spanish-speaking child of immigrants

|

Briana Sanchez frowns at the images on her computer screen.

“I need to add some happier photos in here,” she says. Sanchez, lead photojournalist at the El Paso Times, knows better than anyone the difficult times that the border has been through in the last two years. After spending eight years away, first in college in Georgia and Arizona and then working at newspapers in the Midwest, Sanchez returned home to El Paso in the spring of 2019.

“As soon as I moved back here, we had those patriots at the border, protecting the border on their own volition,” she says. “And then we had the ‘We Build the Wall’ people. And then we had the mass shooting.

How the immigrant founder of a preschool builds community in Northern California through dance, diversity and determination

|

Mi Escuelita Maya is in a working class neighborhood at the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in Chico, California. A mural on the building depicts children from diverse backgrounds flying kites in open spaces. One of the founders, Maria Trenda, helped build the preschool in 2007, just before the Great Recession, on a corner lot just blocks from her home. Her first estudiantes are now entering college.

Trenda’s school is an homage to her past. For 30 years, her mother ran a preschool in Mexico.

From borderlands of Brownsville and Tucson, Chicanx artist explores themes of barriers, belonging

|

Artist Alejandro Macias was born, raised and lived for more than three decades in Brownsville, Texas, communicating the borderlands experience through visual art as a second-generation Mexican American.

In 2019, he moved hundreds of miles west to the borderlands city, Tucson, in Arizona, to continue working on his art and to teach at The University of Arizona in the School of Art. His work, which in part is inspired by Chicanx activist work, draws on artists who transformed the human figure, artistically. His art reflects his and others’ lived experience, striving to find a sense of belonging in the borderlands region. His work also reflects social-political climates of the times.

Macias’ paintings focus on identity, the Mexican American experience within U.S. society, migration, his own family history and the many other families struggling and who have witnessed barriers in the borderlands. He uses images of himself in some work as representative of others with visuals often related to physical and metaphorical barriers in the Mexico-U.S. borderland region, which embodies two nations, two cultures with different identities that often merge together.

Danza cultural helps build important life skills in rural California community

|

Children wearing masks stomp their feet on concrete as they watch the new baile folklórico teacher nod her head and gesture the beats: right, left, right, left. The students are gathered on this Sunday evening in June at the local park in Humboldt County, California and show their excitement with this fun, social activity.

The person leading this effort is Lucy Salazar, the president of Cumbre Humboldt — a local nonprofit celebrating its 2-year anniversary. “Music. Dancing. It’s math.

Today’s border reality: River hazards, refugee child trauma; an end to migrating wildlife

|

There are many perils for humans and wildlife crossing the U.S.-Mexico border, from the hazards of navigating challenging terrain to the trauma of being detained by law enforcement. As tensions rise with each newly erected section of border wall, the impact of hardline policies can be seen taking a toll on the mental, physical, and environmental health of the borderland. Rising waters threaten migrants crossing Rio Grande

Risks to migrants crossing into the U.S. near El Paso have increased with the annual release of Rio Grande water from upriver in New Mexico. The release replenishes the borderlands and allows its farmers to irrigate, but the surge of water and migrants is a potentially deadly combination. Migrants who bypass barriers at U.S. ports of entry to seek asylum by crossing the Rio Grande risk drowning in the high water of the borderland canals.

Like two exhausted boxers, Border Patrol and Central Americans seek respite

|

By Walt Baranger

SUNLAND PARK, New Mexico – Just feet away from a large freeway-like sign declaring “Boundary of the United States of America,” children play in the Anapra neighborhood of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. But this is not exactly true; they gambol in a narrow strip of the United States that lies between the Mexican state of Chihuahua and the American border fence, perhaps a dozen feet of disused territory between the invisible international border and the steel slats that soar up to 26 feet high, forming a rust-colored dotted line across the continent. Happily for the youngsters, the designers of the United States’ border fence failed to take them into consideration. A shoeless pre-teen can easily scramble nearly to the top of the barrier here, and later ask $1 of American passersby who are amazed to see the fence so easily scaled. Bemused U.S. Border Patrol agents occasionally hand out granola bars or other treats to the little hands that reach north through the bars.

Tired but determined volunteers sustain El Paso’s migrant relief services

|

As U.S. border officials detain thousands of migrants along the U.S.-Mexico border every day, another group waits for the men, women and families who have often been walking for days: volunteers. In El Paso, where Border Patrol agents apprehended 136,922 migrants between October 2018 and May 2019, residents have responded to the influx of migrants with meals and shelter. But it’s been eight months since the latest surge of Central American migrants started. Volunteer coordinators have had to adapt their efforts to a timeline that has no end in sight. “The current volunteers are starting to get fatigued,” Christina Lamour, director of community impact for United Way of El Paso County, said.

U.S. border businesses feeling pain of fewer shoppers from Mexico and tariff threats

|

El Paso Street buzzes by 9 a.m. on a weekday. A shop owner with a front-row view of the Paso del Norte Bridge picks up a bedazzled pump and sets it on a box containing the mate. A jackhammer pulses two stores down, caution tape forcing walkers to the street. A steady stream of feet — some quick-paced, others leisurely — move past a Customs and Border Protection officer watching the scene unfold. Life moves, but not at the pace it once did.

12 professors heading to U.S, Mexico border for Dow Jones News Fund Multimedia Training Academy 2019

|

Twelve journalism instructors from U.S. Hispanic Serving Institutions will travel to the U.S., Mexico border region to participate in the 10th annual Dow Jones News Fund Multimedia Training Academy May 31 – June 6 at the University of Texas in El Paso. Thanks to a grant provided by the Dow Jones News Fund, Borderzine organizes this annual training program geared to support multimedia journalism instructors who teach in institutions with a large minority population. Here is a list of the 12 instructors who were chosen and their institutions:

Nancy Garcia, West Texas A&M University

Jacqueline Fellows, University of North Texas

Ana Lourdes Cardenas, San Francisco State University

Stephanie Bluestein, California State University Northridge

Joel Harris, California State University San Bernadino

Farideh Dada, San Jose City College

Fredrick Batiste, Houston Community College System

Adam Schrag, Fresno Pacific University

Tara Cuslidge-Staiano, San Joaquin Delta College

Jenna Duncan, Glendale Community College

Walter Baranger, California State Fullerton

Steve Collins, University of Central Florida

The week-long multimedia-journalism academy has a proven track record of helping journalism educators acquire a new skills in digital storytelling that they can use to help prepare prepare the next generation of Latino college journalists for a competitive media market. “The trainers at the academy understand what educators need to learn about new and emerging technologies to better prepare their students for the fast-changing future” said Linda Shockley, Deputy Director of Dow Jones News Fund. “This quality of instruction at absolutely no cost to participants and their universities is priceless.”

The goal of this experience is to learn and practice news reporting using a variety of digital equipment, software programs and platforms. Participating instructors are expected to translate this learning into training for their students, making them more competitive in the media industry.

The gradual rebirth of Downtown El Paso’s historic buildings

|

When people think of history in El Paso, Texas, they’re likely to dwell on the city’s unique relationship with Juarez, and rightly so. But it’s hard for folks to miss the real historical monuments sprinkled around this border town, even if they aren’t aware of them. They just have to look up. Henry Charles Trost died in 1933 but his legacy still proudly stands in the form of some of the 73 buildings he and his brothers designed in the borderland, dating back to 1903. Structures by Trost and Trost have housed the fabric of the community, including groceries, hotels, schools, houses of worship, department stores and more.

Borderland support builds for tech startups

|

El Paso – once known for its thriving garment industry which eventually crashed because of globalization – is on its way to becoming a smaller version of Silicon Valley, if some tech enthusiasts have their way. Tech accelerators and incubators – businesses that offer El Paso’s 20-plus start-ups a place to work, meet and sometimes funding – are being built to help new firms on their way to becoming the next high-tech success story. One area where the incubators – led by highly educated chief executives, some with doctoral degrees from prestigious universities and a wealth of experience garnered elsewhere – is helping entrepreneurs is in the medical field. Julio Rincon, principal owner of MipTek, based out of the facilities at the MCA Innovation Center, is a biomedical engineer and is working on finding remedies to medical maladies, taking science to the market place. “We find applications by making sure someone wants to buy this,” Rincon said.

Central El Paso’s Manhattan Heights and Five Points neighborhood revitalization fuels new vibe

|

Over the last five years, the Manhattan Heights neighborhood and Five Points business district have seen an influx of new businesses and young professionals, creating a new vibe in this historic Central El Paso area. Susie Byrd,a longtime Manhattan Heights resident and former District 2 City Council Representative, has lived in this historic area since she was in second grade. “These two city blocks were boarded up,” she reflected of the Five Points business district. “Maybe there was like a couple of salons. Not this kind of energy around the core of Five Points development.”

All that is changing as new businesses, such as bars, grills, a yoga studio and now an Ace Hardware Store, are opening in the area.

On the wake of Pancho Villa’s 140th birthday, three women wage a battle against gentrification in El Paso’s oldest neighborhood

|

In September of last year, Romelia Mendoza, one of the two remaining residents on Chihuahua Street, woke up to the sound of demolition crews tearing down the historic buildings next to her home in El Paso’s downtown. “For a second I thought it was an earthquake,” said Mendoza. Antonia “Toñita” Morales, 90, has lived in the neighborhood since 1965. She said she did not hear the bulldozers because she is hard of hearing, but finally awoke to the sound of Mendoza crying hysterically and banging on her door. The two panicked women rushed to try to stop the work, which had begun despite a court order prohibiting the teardown.

12 Journalism professors selected for Dow Jones Multimedia Training Academy 2018

|

Twelve journalism instructors from U.S. Hispanic Serving Institutions will travel to the U.S., Mexico border region to participate in the ninth annual Dow Jones News Fund Multimedia Training Academy in June at the University of Texas in El Paso. Thanks to a grant provided by the Dow Jones News Fund, Borderzine organizes this annual workshop training geared to multimedia journalism instructors who teach in institutions with a large minority population. Here is a list of the 12 instructors who were chosen and their institutions:

Daniel Evans, Florida International University

Mary Jo Shafer, Northern Essex Community College

Lillian Agosto-Maldonado, Universidad del Sagrado Corazon

Julie Patel Liss, Fullerton College

Nicole Perez Morris, Texas A&M-Kingsville

Kelly Kauffhold, Texas State University

Sara V. Platt, University of Puerto Rico

Geoffrey Campbell, UT Arlington

Jesus Ayala, Cal State Fullerton

Lorena Figueroa, El Paso Community College

Darren Phillips, New Mexico State University

Dino Chiecchi, UT El Paso

The week-long multimedia-journalism academy has a proven track record of eight successful years helping journalism educators acquire a new skills in digital storytelling that they can use to help prepare prepare the next generation of Latino college journalists. “The trainers at the academy understand what educators need to learn about new and emerging technologies to better prepare their students for the fast-changing future” said Linda Shockley, Deputy Director of Dow Jones News Fund. “This quality of instruction at absolutely no cost to participants and their universities is priceless.”

The goal of this experience is to learn and practice news reporting using a variety of digital equipment, software programs and platforms. Participating instructors are expected to translate this learning into training for their students, making them more competitive in the media industry.

Sanctuary is in the fabric of El Paso, not the label

|

By John M. Gonzales and Alex Hinojosa

There are 118 so-called “sanctuary cities in the United States, but applying the term to El Paso is like calling Texas a little bit country. With one in four city residents living a bi-national life to manage and work in Mexican factories across the border, traffic snakes bumper-to-bumper every day through checkpoints from neighboring Ciudad Juarez. Twenty-five percent of residents are immigrants — with an estimated 3 percent of the state’s unauthorized immigrants Texas-wide residing in El Paso County. Yet, like other jurisdictions that inherited the sanctuary city tag originally used by immigration control groups to create an image of blanket refuge, El Paso is being told to uphold a law that strikes to the core of its identity. “We’re allowing D.C., and sometimes Austin, to dictate what border policy should be,” said David Saucedo, a mayoral candidate who is pitted against the more politically experienced Dee Margo in a June 10 runoff.

Border Patrol ride along gets real when migrant family appears

|

by Jennifer Thomas

On paper it sounded like the perfect assignment: spend a day along the U.S. Mexican border with members of the El Paso sector of the U.S. Border Patrol as part of the Dow Jones News Fund Multimedia Journalism Training Academy at UT El Paso. Off we went – cameras, notepads and audio equipment in hand. It was hot. 100 degrees. Most of us, have in the least read about, if not reported in some way, the border between the two countries, and the migrants who try to cross illegally into the U.S. What we were not prepared for, was to see an apprehension first hand.

U.S. Border Patrol agent Oscar Cervantes and Joe Reyes served as our guides. Cervantes has been a border agent for more than eight years. Reyes – more than fourteen.

We visited a portion of the 16-foot steel, eight-mile-long fencing that separates Colonia Anapra in Mexico and the village of Sunland Park, New Mexico. The structure has been in place since 2007. “It only takes seconds or minutes to blend into the community,” Cervantes explained.

The El Paso Sector encompasses all of the state of New Mexico and the western tip of Texas, and is one of nine sectors along the Southwest Border of the country. There are 19,000 agents covering more than 250 miles of international border. The section of the border is covered 24 hours a day, seven days a week, but Cervantes insists the fence is not meant anyone out.

College grad in limbo after ICE roundup reveals secret, splits family

|

By Sylvia Ulloa

Jeff Taborda lives in a faded green trailer in an old but neatly kept motor home community in north Las Cruces. Taborda,23, graduated in December from New Mexico State University with a degree in criminal justice, with ambitions to go into law enforcement and eventually join the FBI. He is lean and muscular, working out regularly with his younger brother, Steven. The home Taborda shares with his girlfriend is sparsely furnished, clean dishes in a rack in the sink. “As soon as I eat, I do the dishes,” he told visitors on a recent hot afternoon.