Costs of detaining migrant children at shelters in Tornillo, Texas, and other locations around the country are skyrocketing, with the Trump administration now saying it may cost $100 million a month just to operate the 3,800-bed tent facility outside of El Paso. The administration has not yet provided an accounting of how much in total it has been spending to detain children who either were separated from their parents or apprehended after crossing the border without a parent or guardian. But information provided so far indicates the amount is substantial, forcing the government to transfer hundreds of millions of dollars targeted for medical research, treatment and other programs so that it can care for a rapidly growing number of children in government custody. I have been writing about these issues for Texas Monthly and the Washington Post since June, when the government opened what was then a 400-bed shelter in Tornillo. While the world’s attention was focused on the controversial family separation policy, less attention was paid to other important changes to policies on how migrant children were treated.

Books and backpacks less easy to carry across the border now than before: Mexican students who attend U.S. schools face a new reality in the anti-immigrant age of Trump

|

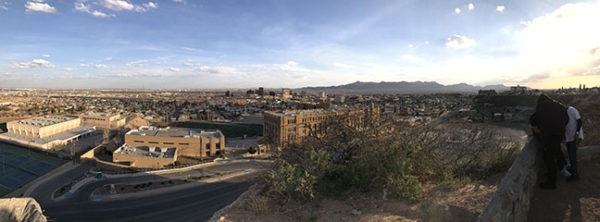

EL PASO – Hundreds of students cross the border from Ciudad Juarez to El Paso daily, carrying heavy backpacks and books and dreams of a better life. Heightened anti immigrant rhetoric across the country and various immigration enforcement executive orders from President Donald Trump have added more stress and uncertainty to their daily lives. Over 1,000 Mexican students attend the the University of Texas at El Paso and about half commute to campus from their homes in Juarez, across the Rio Grande from El Paso, according to a previously published story. The commute is a hardship for many because of the long and complicated commute from their home in Juarez, a walk or a car ride across an international border bridge to have their documents checked, followed by a bus ride to the UTEP campus some five to 10 minutes from downtown El Paso,

Related: In 2016, commuting daily from Mexico to attend school in the U.S. was no big deal for students who budgeted their time well

Most must wake up before dawn to make it to an early morning class, and often don’t return home to Juarez until well past the dinner hour. Depending on the amount of foot or car traffic on the international bridge, the crossing time can vary from 20 minutes to two hours.

Violence, beauty of Mexico influencing emerging border artists

|

EL PASO – As a child at the beginning of the new millennium, Ana Carolina’s city was notorious as a place where hundreds of women went missing. Now a student at UT El Paso, the theme of empowering women is at the core of many of Carolina’s works. For Carolina and other young artists from Ciudad Juarez, art has become a way to process and escape from the ugly reality of the drug wars and other violence that surrounded them growing up. “The disappearance of so many young women is something that really characterized Ciudad Juarez, so I think that really influenced my art a lot,” Carolina said. “I draw women and something that represents them is that they are all facing forward and looking straight at you. My women are strong; we are not just a symbol of sexuality or sensuality in the arts.”

Carolina also uses her art to express the cultural beauty that characterizes this region where Mexico and Texas connect.

College grad in limbo after ICE roundup reveals secret, splits family

|

By Sylvia Ulloa

Jeff Taborda lives in a faded green trailer in an old but neatly kept motor home community in north Las Cruces. Taborda,23, graduated in December from New Mexico State University with a degree in criminal justice, with ambitions to go into law enforcement and eventually join the FBI. He is lean and muscular, working out regularly with his younger brother, Steven. The home Taborda shares with his girlfriend is sparsely furnished, clean dishes in a rack in the sink. “As soon as I eat, I do the dishes,” he told visitors on a recent hot afternoon.

Security, trade, family bind both sides of border

|

By Pam Frederick

From the roof of the commercial customs lanes at the US-Mexico border in El Paso, TX, a line of trucks four lanes wide stretches beyond sight into the Mexican city of Juárez. A similar line of cars inch along, idling for hours, towards the Bridge of the Americas, one of 10 border crossings in the region. The view makes one point perfectly clear: free trade between the US and Mexico is not ending anytime soon. And no one around these parts knows that better than local business owners. “We build everything together,” says Miriam Kotkowski, the owner of Omega Trucking located just three miles from the border crossing at Santa Teresa, N.M. Her father started his business in New Mexico 50 years ago, crossing cattle.

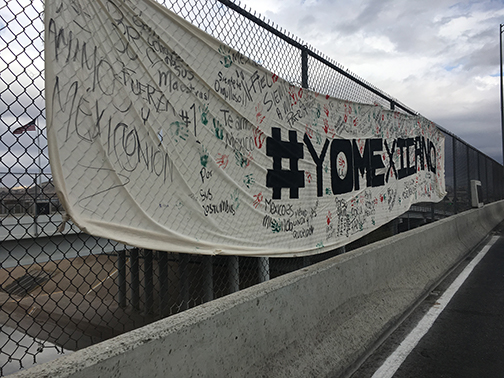

Movimiento Social Digital invita a los Mexicanos a #ConsumirLocal

|

Ante el anunció del presidente de Estados Unidos Donald Trump, de construir un muro en la frontera con México y deportar a miles de inmigrantes sin documentos, usuarios de redes sociales en México generaron varios hashtags defendiendo a México rechazando las medidas del gobierno estadounidense. Hashtags tales como #AdiosStarbucks #ConsumeLocal #MexicoUnidoyFuerte, #MexicoPrimero y #To2Unidos tenían por propósito de invitar a los mexicanos a unirse a un movimiento social digital para ayudar a la economía mexicana comprando productos producidos en la nación. Después de los hashtags, no podían faltar los memes que hicieron su aparición apoyando el movimiento digital que utilizaba a empresas y artistas mexicanos para realizar su sarcasmo humorístico. Muchos de estos memes se podrían considerar graciosos y divertidos. Gracias a la popularidad de los hashtags y memes muchos usuarios de redes sociales publicaban la bandera mexicana como un símbolo de solidaridad, patriotismo y apoyo a este movimiento social entre redes sociales.

Public TV plays important role for children living, learning on the border

|

As a child of the border, I grew up surrounded by two cultures, two languages, and two cities that brought opportunities and experiences not many students in the U.S. kids get. I had the advantage of completing first and second grade in Ciudad Juarez and later coming to the United States to complete elementary, middle school, high school, and college. I remember having to wake up three hours before my classmates in order to be at the international bridge by 6:30 a.m. and make it to school by 7:50 a.m. While this became a normal daily routine for me, I often felt it was unfair that I had to get up so early when other kids slept in because the lived just around the corner from school. Now that I am finishing college, I feel blessed that my have parents gave me a taste of the education in Mexico as well as in the United States. Thanks thanks to the early years in Mexican schools, I have strong skills in writing and speaking Spanish and my Mexican history skills are solid.

Juarez has become a limbo for Central American migrants who decided to delay plans to cross into U.S

|

By Veronica Martinez

For years Casa del Migrante, a shelter in Ciudad Juarez, has been a haven and a crossing point for immigrants coming from the south, but the uncertainty of new immigration policies under the Trump presidency is convincing some of them to remain at the border indefinitely. In 2015 the shelter received 5,600 immigrants. Last year the number increased to more than 9,000, officials said. Ana Lizeth Bonilla, 28, sways back a stroller back and forth watching her two year-old son, Jose Luis, as he sleeps. “Now, we’re just waiting for her,” the pregnant woman says as her arm rests on her baby bump.

Rumores acerca de la forma de inmigración I-407 asustan a los inmigrantes legales

|

Un rumor en las redes sociales que algunos agentes de inmigración están exigiendo que residentes con estatus legal estadounidense firmen una forma abandonando sus derechos de vivir en Estados Unidos ha causado miedo en la comunidad inmigrante, según abogados y oficiales de organizaciones de trabajan con inmigrantes. “Están saliendo comentarios de que los oficiales de inmigración estan forzando a los residentes que firmen este formulario y que abandonen su residencia”, explicó la abogada de inmigración Iliana Holguin. Holguin dijo que los rumores no tienen veracidad. Melanie Luna, quien nació en Mexico y reside legalmente en Estados Unidos por muchos años, también está consiente de los rumores. “Sí he escuchado sobre esa forma, este es un rumor que se ha escuchado solamente por medio del internet”.

Texas sanctuary cities bill worries border community leaders

|

EL PASO – Lawmakers from this border community are concerned about the harm that would result if Texas begins requiring law enforcement and other agencies to act as immigration agents. The Texas Senate on Feb. 9 passed SB4, which Sen. Jose Rodriguez, D-El Paso, called “a thinly disguised attack on immigrant communities.”

The so-called “anti-sanctuary cities” bill would allow the state to penalize cities over policies that obstruct enforcement of immigration law or discourage police agencies from inquiring about a person’s immigration status. The Texas House is now considering its version of the bill. The senator says he, along with other opponents of the bill, offered amendments to decrease the negative impacts the passage of bill would have on health, safety and social life of communities.

Muslims feel embraced by border community, even in times of Trump

|

El Paso, TX – The recent temporary ban on seven Muslim-majority countries signed by President Trump came with a surprising instantaneous outpour of support towards Muslims and refugees across the U.S., and on the border. About 3,000 to 4,000 Muslims live in the Sun City, said Omar Hernandez, Public Affairs Director at the Islamic Center of El Paso located in the West side. Despite a rise in anti Muslim sentiment in some part of the country, several El Paso Muslims say they continue to feel a warm embrace from El Paso residents. “I have fallen in love with El Paso because of its people,” said Zahra Taki, 31, a student at El Paso Community College. In 1987, Taki was two years old when she and her parents emigrated from Kuwait.