By Veronica Martinez

For years Casa del Migrante, a shelter in Ciudad Juarez, has been a haven and a crossing point for immigrants coming from the south, but the uncertainty of new immigration policies under the Trump presidency is convincing some of them to remain at the border indefinitely. In 2015 the shelter received 5,600 immigrants. Last year the number increased to more than 9,000, officials said.

Ana Lizeth Bonilla, 28, holds the hand of her 2 year-old son at Casa del Migrante in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua where they’ve been staying for more than a week. Photo by Veronica Martinez

Ana Lizeth Bonilla, 28, sways back a stroller back and forth watching her two year-old son, Jose Luis, as he sleeps. “Now, we’re just waiting for her,” the pregnant woman says as her arm rests on her baby bump. Her husband Luis Orlando Rubí, 23, just started a new job at a paper factory. It is their ninth day at the shelter.

Staying in Juarez wasn’t the original plan when the family left Honduras in 2016. “We came with the purpose of crossing, but after seeing the situation in which the President of the United States said he was going to separate children from their mothers my husband opted for us to not to cross and stay in Ciudad Juarez for a while.”

Back at home in Honduras, Rubí owned a cell phone repair business and made piñatas, while Bonilla sold fruits and vegetables. Once crime rose, delinquents demanded Rubí pay them a fee to keep the business open.

“My husband agreed to pay the first time. The second time they asked for too much money, so he said no. On Mother’s Day they came to our home and tied me and my son up and made us call my husband as he was at his mother’s house. When he got home (and saw this) they beat him up. When he refused to pay they told him to join them in illegal acts. Since my husband didn’t want to do it he told me I could stay or leave with him. This is how we left Honduras.“

The family left for Tapachula, Chiapas, with no documents and stayed for six months. There they managed to save some money and Rubí decided to regularize their immigrant status. Mexico granted them permanent residency as refugees.

From there they moved to the town Escuintla, an hour away from Tapachula, then to Tonalá, another town in Chiapas. From there they traveled to Arriaga where they stayed for a month and volunteered at a shelter.

On New Year’s Eve, Bonilla said, they left Chiapas for Mexico City, and finally departed by bus to northern Mexico. Rubí, Bonilla, and their son José Luis reached Monterrey and later on Torreon. Two weeks later they reached the bus central in Juarez, and Grupo Beta, a program operated by the National Institute of Migration (INM) of Mexico, transferred them to Casa del Migrante.

Rosaries, flowers, and inmate wrist bands serve as offerings from the immigrants for Saint Jude’s statue at Casa del Migrante in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua Tuesday. Saint Jude is known as the patron of impossible causes. Photo by Veronica Martinez

Since 1982, the shelter has offered a bed, three meals, medical and psychological attention and legal counseling to immigrants from Mexico and Central America. Run by the Catholic dioceses of Ciudad Juarez they receive an average of 250 to 300 immigrants each month.

“The journey through Juarez was going to be gentler until we could see if I was going to be able to cross,” said Bonilla referring to her pregnancy, “because there was also the possibility of him [Rubí] not crossing with me. As a mother it was hard for me to separate the children from their father. It didn’t make any sense for me to enter the United States if he wasn’t coming.”

According to humanitarian organizations, since the Trump election more immigrants from Central America are staying put at the border city.

“Recently, Central Americans are staying,” said Ivonee Lopez de Lara, coordinator of human rights at Casa del Migrante. “The difference is that (before) the Central Americans would come, work, and then leave. Now what they’re doing is that they’re staying longer to see what’s going to happen.”

Lopez de Lara said there are additional risks for the undocumented Central American migrants who decide to remain in Juarez. “They’re now a target for people involved in organized crime because they know (the immigrants) are vulnerable since they work based on their necessities.”

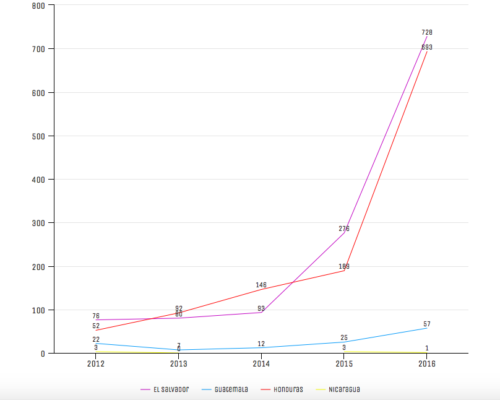

According to data from the Institute of Migration of Mexico the number of resident cards issued by Mexico to Central American refugees has risen for the past five years. The graph above shows the number of resident cards issued by Mexico from 2012 to 2016. Chart by Veronica Martinez

According to Adolfo Castro Jimenez, coordinator of the Human Rights State Commission of Ciudad Juarez, during the months of January and February of this year around 1,500 undocumented immigrants were deported through El Paso. He said that a high influx of undocumented immigrants in the city creates greater economic difficulties for everyone.

“A lot of Central Americans now see Juarez as a place to stay,” Castro Jimenez said. “They come to Juarez and don’t want to cross to the United States anymore because of Mr. Trump’s policies. They see Juarez as a place to live and stay and that’s important. Obviously the city is going to need more resources because of the incoming demand and that’s going to be a problem. Here in Juarez we get the people from the South but we also receive the ones (being deported) from the north.”

Some community shelters and churches that help migrants are aware of possible mass deportations to Juarez of undocumented immigrants from the United States. Although the mass deportations promised by Trump before and after his election have yet to materialize, Casa del Migrante is already preparing its facilities for an expected influx.

“We are accommodating certain areas of the place; the living room, the TV room, the dormitories. There’s an exercise area already prepared with mattresses and blankets. Through the diocese we’re looking for churches that can serve as shelters,” Lopez de Lara said.

Unlike Bonilla and Rubí, not all Central Americans migrants have permission to remain in Mexico because their goal is still to cross into the United States when they have the chance.

“They don’t want to get legal status for themselves because it is not their goal to stay here,” Lopez de Lara said. “This isn’t one of their priorities.” she said.

Bonilla agrees that returning to Honduras is no longer part of their future plan and they intend to remain in Ciudad Juarez. “If we can make a living here we stay here, and if not, God will decide.”