In September of last year, Romelia Mendoza, one of the two remaining residents on Chihuahua Street, woke up to the sound of demolition crews tearing down the historic buildings next to her home in El Paso’s downtown.

“For a second I thought it was an earthquake,” said Mendoza.

Antonia “Toñita” Morales, 90, has lived in the neighborhood since 1965. She said she did not hear the bulldozers because she is hard of hearing, but finally awoke to the sound of Mendoza crying hysterically and banging on her door.

The two panicked women rushed to try to stop the work, which had begun despite a court order prohibiting the teardown.

“It was horrible, they just looked at us and laughed,” Mendoza recalled.

With an aging Toñita besides her, Mendoza said they were not able to put up much of a fight. Within minutes, a half-dozen of the buildings they had been desperately protecting had gaping holes. Part of the issue is a controversial multi-purpose arena, part of a voter-approved bond measure. But opponents claimed a bait-and-switch on the part of the city, and a lawsuit over the issue continues to wend its way through the court system.

Though frantic calls to police and politicians kept the crews from finishing the job, the rubble and fences that now surround those structures are a stark reminder of the bureaucratic limbo where they reside. Nearly a year later, Duranguito is stuck between those who say the neighborhood must be preserved at all costs — calling potential development a giveaway to wealthy interests — and those who say an increasingly crowded city needs to utilize all its land in the best possible way — unmoved by the historical elements in El Paso’s oldest settlements. Neither side seems much interested in compromise.

Just a day before, tensions reached a boiling point when the same demolition crews threatened to tear down the same buildings in violation of a Texas court injunction that prohibited them from doing so. But residents and activists formed a human blockade and fought off the crews, or so they thought.

Angie Martinez, a long-time resident of Duranguito who grew up in the famous “La Mansion de los Gatos,” learned about the demolition when Morales and Mendoza called her in tears and begged her to get help.

“They came in the early morning like the wolves at night and brought the bulldozers and started banging each building,” Martinez said.

Martinez arrived within minutes to the neighborhood she once called home in the 1940s and 1950s to find that her grandparents’ home had been destroyed in the ambush.

“I cried for days,” Martinez said.

She fondly remembers her grandmother making homemade corn tortillas. Without any warning, those fond-held memories of the place where she had been a child and grown up vanished.

“This is why I fight. In honor of my grandparents’ memory,” Martinez added.

Slide to see before and after images

Later that day, droves of neighbors and activists went out to protest the demolition but they were met with the force of police in riot gear. During the standoff, the lines were decisively drawn in the battle over Duranguito and its fate, a battle that Martinez says residents do not intend to lose.

El Paso Will Never Be Las Vegas

“They want to turn this into Las Vegas but that will never happen. The arena they want to build here will never happen. We are not going anywhere. Why in Duranguito? Because we are poor? People just come with money thinking they can destroy buildings and they don’t care about the people,” she said. “I’ll tell you something, even if they offered me $12,000 (to relocate) I would not accept it. My home has no price.”

Martinez, Morales and Mendoza know the bulldozers may return, so they say they are not taking any chances and are keeping a watchful eye over what remains of their beloved neighborhood.

“It happened once, but it will not happen again,” Martinez said. They take turns patrolling the streets 24-hours a day to make sure the remaining buildings are not destroyed. “We are here in the snow, rain, cold, hot. Whatever it takes,” Martinez said.

“There are people here even at night. We are vigilant. We are afraid that they could come and start a fire. That’s why we try to stay awake, at night especially because they can come and just go through and they can just throw something into the building and it can catch fire. So this is why we are here.”

“They don’t understand. They think we are just fighting for old buildings. But we are fighting to preserve our heritage and for our culture, ” Martinez said. “We draw strength from people who fought over this land. It’s in our blood.”

Business Owners Push for Development

But for Luis Cordova this is not a matter of preserving history or culture. It’s a matter of economic survival. “We want entertainment. We want all the different options to come downtown for. You want to build something trendy and different, and something we haven’t seen before,” Cordova said. “This [Duranguito] is something that has been there for many years and it’s never really hit so it’s a high risk to try to go invest into it.”

Cordova, the owner of the trendy Fainting Goat restaurant and pub, is no stranger to failing businesses in the area, in fact he has seen many come and go over the last decade. “I think they need to clean up this area. I think the best would just be to drop it and do what we gotta do. In my humble opinion it is probably one of the ugliest parts of the city. So we just need to move on,” he said.

Cordova now owns three restaurants on the outlying boundaries of the Duranguito neighborhood. Many of the city’s political and business leaders, like Cordova, are convinced that the Duranguito area must undergo sweeping changes to fit the city’s vision for a modern city. They believe that a revitalized downtown area could have an enormous payoff.

The city of San Diego, for example, harnessed the power of neighboring Tijuana to develop Las Americas, a revitalization that created over 1,000 new jobs, $33.7 million in additional sales tax revenue, and an additional $14.8 million in property tax revenue. In Columbus Ohio, the Nationwide Arena transformed the city’s downtown into a vibrant neighborhood with urban residences, parks, an abundance of shopping, entertainment, restaurants and hotels, boasting over 2.7 million visitors a year.

“There’s a lot more attention being focused into this part of west downtown, especially the restaurants and bars from the plaza to the east end,” Cordova said. “We are a block away from the stadium. This is the best place to come pregame or after the game. There are a lot of options that can go into that arena, from soccer, concerts, festivals. We are doing a lot of festivities in the middle of the street but to have a special assigned arena for it, people would love it. When they bring concerts here or even soccer the amount of people quadruples.”

The arena is the largest project in the $473 million bond issue approved by voters in 2012. El Paso’s economy in 2018 is expected to grow at a slightly slower pace than in 2017, and slower than growth projections for the United States economy, according to University of Texas at El Paso economists. According to the study, “Borderplex Economic Outlook to 2019,” the El Paso economy is projected to grow 2 percent this year to $27.4 billion.

Historian says City Wants to Disappear Duranguito

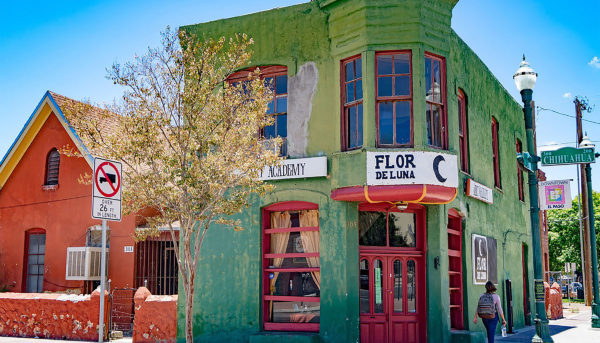

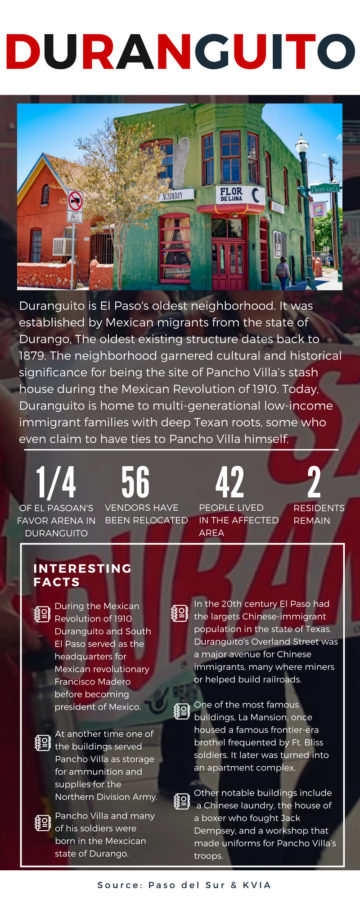

On the day before what would have been Pancho Villa’s 140th birthday, historian David Romo braved the 100-degree El Paso heat to point out a dilapidated green and white edifice that served as the Mexican revolutionaries’ stash house: Casa Clandestina.

The building sits on Leon Street in middle of a tiny neighborhood caught between the forces of progress and history. There are fewer than 100 people left, pushed out by increasing rents or enticed by developer buyouts. Its quiet streets seem to be the exact opposite of what city leaders want: Despite the fact most residents are of social security age, kiosk-style maps call the area a “nightlife and entertainment district.”

The building sits on Leon Street in middle of a tiny neighborhood caught between the forces of progress and history. There are fewer than 100 people left, pushed out by increasing rents or enticed by developer buyouts. Its quiet streets seem to be the exact opposite of what city leaders want: Despite the fact most residents are of social security age, kiosk-style maps call the area a “nightlife and entertainment district.”

“This place can be restored,” he said, acknowledging its rundown streets and buildings. “There can be a rebirth. Who knows, maybe you include the damaged, put in glass windows full of flowers blooming out of it.”

In addition to the stash house, Romo pointed out the Coffin House on West Overland Street, which he said was one of the first wooden building in the city and the oldest still standing. The owner, Cameron O. Coffin, made soda bottles, and dozens are still in the ground below the property. Just down the street is the Chinese Laundry Building, which has stood for more than a century, though its owner withdrew an application to have it declared a historical landmark last year.

The neighborhood has a feel of being in suspended animation. A wide swath of Chihuahua Street remains fenced off with a gaping hole in the side of the a half-dozen buildings, include the former Flor de Luna Gallery. Outside a mail carrier and a parking authority official emptying meters of the few coins he finds, the streets are generally empty.

For his part, Romo sees a darker motivation by developers and city officials in the rubble.

“I think that erasure precedes what they want to do,” he said. “First you destroy our history, then you deport us. As in, we have never been here before. You disappear us symbolically, then you disappear us physically.”

Why I refuse to leave Duranguito

For Mendoza, her home is more than just a structure. It is a fight to keep memories alive and pass them on to future generations.

“One of the reasons I want to keep my house is because it has an emotional value,” she said. “There are a lot of memories here. That is why I don’t want to move out.”

Mendoza has been living in her home for 40 years and wants the ability to pass it on to her daughter and grandchildren.

“I won’t sell my house. I won’t do it,” she said. “Some people ask me what the city has offered me. I told them that the city didn’t offer me anything because I don’t want to talk to them.”

Mendoza said that accepting a deal from the city would betray the neighborhood and its roots. Although it has been an intense and exhausting process, continuing to fight is the only option.

“I want to stay firm until it’s possible and I have faith we will win,” she said.

Toñita Morales arrived in the neighborhood in 1965 and has lived in her current home since 1988. She said the fight for Duranguito transcends physical barriers and focuses on the value of his space as a community center.

“In this neighborhood we got rid of all those bad things. We got rid of the prostitution, the thieves and we cleaned everything (since 1988),” she said.

The syringes, drug dealers and prostitutes have been transformed into a residential and cultural space, said Toñita, but it is more more than that.

“I’m not fighting for my house,” she said. “I am fighting for my community.”

This multimedia story was produced for the 2018 Dow Jones Multimedia Training Academy by Jesus Ayala, Lillian Agosto-Maldonado and Daniel Evans.