In 1999, the Mexican poet Sor Juana Ines de La Cruz began her transformation into becoming a Chicana.

The 17th century Hieronymite nun, one of Mexico’s best poets, was already dead by about three hundred years before the term Chicana came to be used, but nonetheless, with the publication of Alicia Gaspar de Alba’s ground-breaking novel, Sor Juan’s Second Dream, she became a Chicana feminist icon.

Today Chicana intellectual activists know who she is and how important she is to Chicana identity and resistance. She was too brilliant to want to get married to some “hombre necio.” She wanted to develop her mind and resist convention.

Today Chicana intellectual activists know who she is and how important she is to Chicana identity and resistance. She was too brilliant to want to get married to some “hombre necio.” She wanted to develop her mind and resist convention.

Gaspar de Alba’s novel may have been part of a late 20th century Zeitgeist that liberated feminine images from male historical narratives and redefined their socio-political significance, like Sandra Cisneros did for La Malinche, but it is certain that de Alba’s book influenced Chicana feminist interpretation of Sor Juana’s life. Her story became about self-determination, empowerment, the narrative of a mind so great she could not be held down by the confines of patriarchy.

Sor Juana became a Chicana.

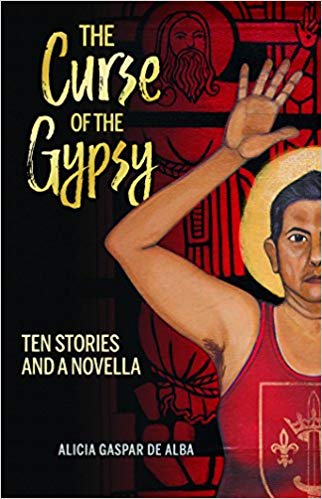

In her latest novel, The Curse of the Gypsy: Ten Stories and a Novella, Gaspar de Alba may very well do the same thing for a relatively unknown historical figure, the Catholic Saint Liberata Wilgefortis, the bearded woman.

This novella within Gaspar del Alba’s new book has the epic title, “The True and Tragic Story of Liberata Wilgefortis Who, Having Consecrated Her Virginity to the Goddess Diana to Avoid Marriage, Grew a Beard and Was Crucified.”

It creatively takes place during the Roman empire, when Christianity was still emerging as a rebellious religion. The legend, as Gaspar de Alba tells it, starts with a rich and powerful woman, the Governor’s wife, who gives birth to nine daughters, all of them born with “birth defects;” for example, two of them without hands, one of them a hermaphrodite, and one with fur all over her body.

The hairy one is Liberata Wilgefortis, and she is the only child the Governor’s wife lets live. She orders her midwife to drown the other eight. She would have killed all nine of the girls, but the midwife, Basilia, pleads with her to let at least one of them live. Basilia then prays to the goddess Diana about the fate of the other eight, asking her for direction in making the fateful choice that will drive the story.

The goddess Diana is, of course, a Roman God, but she has remained a relevant deity for goddess worship even today, taking the role some indigenous women might give to Tonantizin, the Magna Mater, the Mother God.

The fact that the protagonist of the story, Basilia, a midwife –a profession that is itself an archetype of feminist spirituality – is close to the goddess Diana suggests that this is a story of female spirituality. There were many other Roman gods, masculine deities like Jupiter, Saturn, Mars, but they have little or no place in the story of Wilgefortis and Basilia.

In fact, Basilia feels close to a trinity of world goddesses, Bridget (Ireland), Isis (Egypt), and Minerva (Etruscan), which reflects her mystic strength in that she was not tied to a national or regional religion. Instead, she feels connected to goddesses that she believes rule and influence the various worlds, birth, love, and death. Well into the story, a man witnesses Basilia’s wisdom and charity, and he suggests that she should become a member of the new religion, Christianity, but she responds, “I shall never give up on my goddesses, sir.”

The governor’s wife orders the midwife to kill all nine of the girls, but Basilia convinces her to keep the most “normal,” the hairy baby, and she promises to drown the other eight in the river, which she does not do, even though she is commanded to do so by her spiritual leader, the MAGE, a patriarch. She finds families for the girls, who grow up to be happy young women. They will never marry, because of their deformities, but this does not seem to impede them from living full and meaningful lives. All is well, for a while.

I won’t tell what happens to the girls, but the story comes to an inevitabile, heartbreaking conclusion. The narrative of course is focused on Liberata Wilgefortis, whom the governor’s wife raises as her daughter, although she mostly hides her from the governor, who would kill the girl if he saw how hairy she is.

The midwife feels an affinity for little hairy Wilgefortis. But her Mage condemns her to isolation from other humans for letting the other girls live. The two are separated for 12 years.

During that time, Basilia lives in a cave. She eats nuts and berries and placenta from the birth of the nine girls, and studies mysticism and science and the occult, reads all night long, and takes walks in the forest during the days, sleeping on rocks.

To find wisdom in a cave is of course a powerful and oft-evoked symbol of great mystic narratives, like Moses de Leon, who in 1213 in Spain found the Zohar in a cave, the primary text of the Kabbalah, not to mention the cave of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra.

In fact, an important aspect of the book is its references to different mystical and spiritual incantations and rituals. The stories provide us with details that could only come from painstaking research, or like the writer Tim Z Hernandez tells me, “Geeking out on the research.” There are specific and accurate details about Roman and Gypsy spiritualty, customs, and language.

As Basilia was living like a mystic for twelve years in the cave, Wilgefortis grew up, and the hair on her body disappeared, but she was skinny and ugly, and for that the father hated her. He wanted to marry her off as soon as possible, but who would marry her? He finds the only man willing to do so – a decrepit old man, decades her senior, who just wanted a young woman with whom he could breed.

Like Sor Juana Ines, Wilgefortis does not want to get married. She may lack the intellectual vigor of Sor Juana, but she has an incredible insight into the spiritual world, and even communicates on a regular basis with the spirit of her dead brother. She, like her midwife, has access to the spirit world.

After 12 years, Basilia emerges from the cave and becomes the nurse for Wilgefortis. And they become very close. When the father tries to marry her to the old man, she resists, and the midwife cannot help but help her.

Through incantation or prayer to the goddesses or simply through fate itself, Wilgefortis grows a beard, so no man will ever want to marry her. The beautiful irony surfaces that in a time when women only wanted to get married, Wilgefortis only wants to NOT get married. Like Sor Juana, she wants to determine her own fate.

What makes this book an important part of the Latinx literary canon is that it reinterprets this mythical Catholic figure through a Latinx feminist perspective. Wilgefortis becomes Chicana.

But perhaps even more important for the reader of fiction is that at the root of these stories, one can sense the love of the writer has for writing. Along with the story of Wilgefortis, Gaspar de Alba writes interconnected stories about a gypsy girl named Margarita, who is impregnated by the poet Garcia Lorca in Granada, Spain, a story which organically ends up years later in El Paso, TX.

Gaspar de Alba loves to tell stories. Every detail is packed with the desire to welcome the reader into this real world of the imagination, every detail bursting with the spirit of sharing:

“Once her house (Basilia’s) had been a free-standing dwelling, a round house in the Celtic style, the woven branches of the round walls daubed with clay and dung, and a high sloped roof touched with rye.”

And if a writer loves to tell a story, the reader is going to love to listen to this one.