Francisco Uviña was 19 when he crossed the U.S. border in search for work in the 1950’s. Like many other Mexican laborers of that time, Uviña was signed up for the Bracero Program which offered a solid wage and an opportunity of a lifetime to live and work in the agriculture sector of the United States.

Uviña first heard of the Bracero Program from friends and neighbors in his hometown of San Luis de Cordero, Durango. In the spring of 1953, he then joined a caravan of over 1,000 laborers who traveled by bus to to Chihuahua City, Mexico, to register for the program.

This year marks the 76th anniversary of the Bracero Program, a labor program that allowed more than four million Mexican men to cross into the United States to work the fields after U.S. men went off to fight in World War II. The program ran from 1942 until 1964.

Rio Vista Farm still stands in Socorro, Texas. The building is dilapidated and old but it is one of the last remaining processing centers left in the nation.

Last fall, to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the program, the National Trust for Historic Preservation offered a public tour of Rio Vista Farm in Socorro, Texas. County. Rio Vista Farm was established in 1915 as El Paso County’s second “poor farm” for public welfare programs.

Uviña and other former Braceros were invited to return to the farm, which was used as one of five processing centers for migrant farmworkers during the Bracero Program. Uviña attended with his daughter Magdalena Ronquillo. The Rio Vista Farm was designated as a National Treasure in 2016.

Yolanda Chavez Leyva, a professor at the University of Texas at El Paso who specializes in Borderland History and Chicano History, described the Bracero Program as the largest migration of people across borders in North America in the 20th century.

“There were about 6.5 million contracts in the years of 1942 to 1964, but that’s not 6.5 million people because they’d sometimes have more than one contract. But at the height of the Bracero Program there were about 3 million men here at one time,” Leyva said.

The process of registering for the program in the U.S. was similar for all of the migrants.They were transported from part of Mexico to various processing centers throughout the U.S. before being allowed to work.

For Uviña, that meant he was registered in Chihuahua and then bused to El Paso, Texas, where he was processed and relocated to the Rio Vista Farm. At the facility, he waited with thousands of other Braceros for a job offer to work the fields in other parts of the country.

“I crossed because it was the new thing in Mexico. People were excited. Some sold their chickens, their pigs, their cows for the opportunity to go to Chihuahua and become a Bracero,” Uviña said.

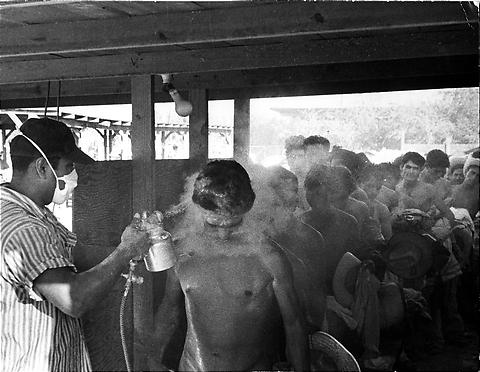

At the Rio Vista Farm facility, Uviña and the other Braceros went through a registration process that included having to strip naked to be fumigated with DDT, a pesticide meant to kill lice.The U.S. banned the use of DDT in 1972 due to adverse environmental effects and potential human health risks.

At the Rio Vista Farm facility, Uviña and the other Braceros went through a registration process that included having to strip naked to be fumigated with DDT, a pesticide meant to kill lice.The U.S. banned the use of DDT in 1972 due to adverse environmental effects and potential human health risks.

Despite the debasing process, Uviña remembers Rio Vista Farm fondly for the quantity of food and how well he was treated by the staff.

“The dining room was around 100 feet and there was a table that stretched from one end of the room to the other. That’s where we all ate. Beans, rice, and tortillas,” Uviña said.

After passing the inspection Uviña spent the following six years working in the cotton fields of Fabens, Pecos, and Socorro as a Bracero. Over time, he proved to be a valuable worker with nimble fingers, picking up to 400 pounds of cotton a day from Monday through Saturday on eight-hour shifts. Although he earned just 50 cents an hour, he said that was more than he would have earned doing similar work in Mexico.

Francisco Uvina, former Bracero, sits outside of his house in Sunland Park, NM with a picture of his younger self.

Uviña first labored in Fabens, where he lasted a year. After Fabens he returned to Rio Vista Farm to wait for the next available job. The next offer came from Pecos, Texas, a town that no Bracero wanted to go to because the work was hard and the pay was not as good.

He says that Pecos had tall, disheveled, and wild fields of cotton that were almost impossible to pick. To make matter worse, Braceros would get paid by the pound instead of by the hour. Many Braceros, he explained, preferred to work in California where the pay and the climate were better.

“We didn’t want to go to Pecos because they said it was pretty bad. We wanted to go to California or other states. So, the Mexican Consul went to see us and with a megaphone he said, ‘boys, right now there’s no other job but in Pecos and whoever doesn’t want to go to Pecos will be sent back to Mexico.’ That was unfair because we had a right to choose the job we wanted. But we thought that after everything we had sacrificed there was nothing else we could do but work in Pecos,” Uviña said.

The photograph shows braceros working the fields, where they would stay from sunrise to sunset. Thousands of braceros were brought in to perform stoop labor, a task that causes back injuries resulting from the constant strain of bending over all day. Photograph by Leonard Nadel, National Museum of American History.

After four months of living and laboring during the harsh Pecos winter, Uviña returned to the border where he was hired by a local farmer, Harvey Hilley, to work his cotton field in Socorro. There he became the top picker working alongside other Braceros that couldn’t keep up with his daily collection of 400 pounds. Despite his outstanding work, Uviña said he never received a raise.

Uviña worked for Hilley until the end of the Bracero Program in 1964. He then relocated to Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, where his mother and four sisters lived and set up his own welding shop.

Uviña’s father taught him to weld at the age of eight and when his father abandoned his family he used his skill to earn one peso a day to help his single mother. Once he opened his own welding shop, he started to earn five hundred pesos a day plus side jobs.

Ciudad Juarez also provided Uviña with a family. He married and after years of living in Mexico he and his family relocated to Sunland Park, New Mexico.

Ronquillo says that her father’s stories from his time as a Bracero were a part of her life growing up and, despite the hardships he faced, he made the best of his situation.

“He’s kind of like a gentle person – he kinda sees the good in people rather than the bad, he sees the glass half-full rather than half-empty,” Ronquillo said. ” Even when his mother had to beg for food when he was a child – he never held bad feelings for (his father). He forgave his father. Even after all of that he maintained his goodness.”

Related stories:

Historians chronicle lives, dreams of Mexican braceros in U.S. labor program

Song inspires writer to search for nameless victims in ‘Deportees’ plane crash