EL PASO — Emilio Solis Pallares,92, sits at his home in Fabens, Texas, listening with surprised amusement to his own voice for the first time 12 years after his story was cataloged along with the tales of hundreds of other bracero farmworkers as part of a national program by the Smithsonian Institution.

Emilio Solis Pallares. Photo by Tanya Carbajal, Borderzine.com

“Yes, that is me and the story still remains true,” said Solis, who labored in the cotton of fields of Tornillo, Texas, for 15 years in the 1940’s and 1950’s as a member of the federal Bracero program, which recruited 4.6 million Mexican citizens to work in agriculture in the United States.

Solis’ story was just one of more than 900 interviews conducted by the Institute of Oral History at the University of Texas at El Paso. More than 3,000 oral histories of braceros can be listened to online at the Bracero History Archive. Emilio’s oral history can be found here.

“We interviewed them at an old age. We were able to contact the braceros because of word of mouth,” said Anais Acosta, of the Institute of Oral History at UTEP.

The Bracero Program was a guest worker program started in 1942 as the United States became embroiled in World War II. Dr. Yolanda Leyva, professor and Chair of the Department of History at UTEP and co-director of Museo Urbano in El Paso’s Segundo Barrio, said that many believe the program began because U.S. agricultural employees went to war and there were not enough men in the fields who could do labor. Historians now contend that the labor shortage was caused because of the low wages paid to U.S. agricultural workers.

Related: Song inspires writer to search for nameless victims in ‘Deportees’ plane crash

The Bracero History Archive was a collaboration between George Mason University, the National Museum of American History, the Smithsonian, Brown University, and UTEP.

Acosta has worked at the Institute of Oral History at UTEP for 14 years and she was invited to conduct the bracero interviews in Spanish.

“It was an amazing experience. I got to know them on a personal level,” Acosta said.

She described stories of their suffering, difficult working conditions, low wages, loneliness from being separated from their family, and difficulty in obtaining money withheld from their paychecks and still owned to them.

“I was really honored to participate in this project,” Acosta said. “I am Mexican and I didn’t know about this program. It is really rewarding to understand and to know about the problems they faced. Working conditions in Mexico were not good so they decided to leave their families and their country behind just to get a better quality of life.”

Anais conducted interviews all over the U.S. but mainly in California. She also tape-recorded interviews in El Paso and Las Cruces, New Mexico, and even some in Mexico, many of them inside the braceros’ homes. Interviews with family members and people working with braceros were also done to get different perspectives about the program. More than 900 interviews were conducted and then transcribed, sent to the main bracero archive and edited. They are now available at the Bracero History Archives website.

The interviews reflect the sense of pride the braceros felt at having their stories collected for a national history project, Anais said.

“More braceros would tell more braceros and we just got into contact with them. Some of them were reluctant to speak because of all the hardships that they faced. We had a questionnaire for the braceros. All the questions were the same but the answers are what made the story unique,” said Acosta.

According to Leyva, the bracero program, “…ended in 1964 and that is one of the ways that you can tell that the program really wasn’t about a labor shortage caused by the war because (the program) lasted almost 20 years past the end of the war.”

To U.S. employers, Mexican workers were a logical replacement for U.S. workers. After deporting about one million people of Mexican descent before the war, the U.S. decided to bring them back as guest workers to deal with labor shortages. The government maintained that the workers were needed as hundreds of thousands of U.S. men were deployed to fight in Europe and throughout the Pacific.

The 4.6 million, six-month-long work contracts for Mexican citizens were issued between 1942 and 1964. But the contracts could be renewed for longer periods of time, sometimes lasting for a decade or longer.

Although the Mexican government required that U.S. employers offer the Mexican workers sanitary working conditions and adequate wages, that wasn’t always the case. The first-person interviews and testimonials of the guest workers tell a different story.

Leyva, who has reviewed documents from the program, said some of the men felt exploited. Still unresolved is which country is responsible for returning to the workers the 10 percent that was withheld from their paychecks and supposedly deposited in U.S. banks and then transferred to Mexican banks. Farmworker advocates continue to investigate what happened to the money so it can be returned to the braceros or their family members.

“The tragic thing is that they never got that money,” Leyva said. “The money that was taken from the paychecks, if you think about interest accrued over all those decades would be in the millions of dollars. The money had been given to Mexican banks but the Mexican banks said they did not know what happened to it.”

As a result of a class-action lawsuit filed in California in 2001, the Mexican government has paid on and off some of the money to some braceros but not all of it.

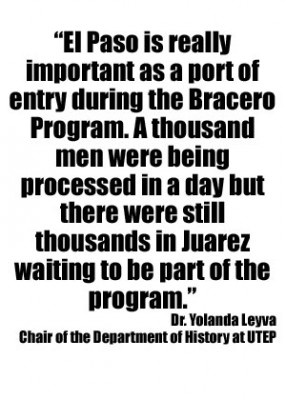

Interestingly, the very first braceros who crossed into the U.S. in 1942 entered from Juarez to El Paso, which was the main port of entry for the program. However, for many years the Mexican government would not allow braceros to work in Texas because it considered Texas a racist place for Mexicanos, Leyva said.

Sometimes, when the contracts were being renegotiated by both countries, the workers learned to cross the border without papers to work for U.S. employers who they had worked for previously, said Leyva. She said this encouraged undocumented migration into the U.S. and in the 1950s led to a “huge” deportation campaign by the federal government called “Operation Wetback”.

Sometimes, when the contracts were being renegotiated by both countries, the workers learned to cross the border without papers to work for U.S. employers who they had worked for previously, said Leyva. She said this encouraged undocumented migration into the U.S. and in the 1950s led to a “huge” deportation campaign by the federal government called “Operation Wetback”.

Leyva said many braceros kept letters from their employers saying they were “great workers and trustworthy.” The letters “were like gold for the workers” because they would show the letters to U.S. authorities when they wanted to return to work in the U.S. Some of the employer letters were written in the 1950s, she said.

“I lived a comfortable life,” said former bracero Solis, explaining that his boss helped his wife and children get papers to stay in the United States.

During the 1950’s when the Lower Valley in El Paso county was a big cotton producing area and negotiations to renew the bracero program broke down, the U.S. Border Patrol agreed to let undocumented Mexican workers cross into El Paso to pick the cotton without arresting them.

“You see a lot of things where the law is not being followed because agricultural employers are so powerful,” said Leyva.

Rio Vista Farms in the Lower Valley, which still stands, was the main processing center for the braceros.

Leyva talked to a woman a few years ago who was a secretary there in the early 1960s when she was 17. The woman, whose name Leyva doesn’t remember, would help the workers fill out the contracts and give each of them a bologna sandwich.

“El Paso is really important as a port of entry during the Bracero Program,” Leyva said. “A thousand men were being processed in a day but there were still thousands in Juarez waiting to be part of the program.”

Because neither Juarez nor El Paso provided shelter or food to the workers, Leyva said some would live on the streets in Segundo Barrio next to the bridge until buses arrived to take them to their place of employment.

Acosta said she was deeply affected by the story of a bracero from Sonora who decided to stay in the U.S. after the end of the program and now owns a landscaping and construction business in Las Cruces,. He is a good example of the American dream, she said.

“He worked in the fields and then he pursued his dream.”