The history of women on El Paso’s police force dates back to 1913, but much has changed over the years.

“Women were seen more as social workers than police officers because it was a very male-dominated occupation,” said Egbert Zavala, an associate professor in the Criminal Justice Department at the University of Texas at El Paso.

Early police work by women mostly involved looking for runaway girls, making calls on community residents, patrolling the streets and arresting prostitutes.

“There was this idea, back in the day, that males had to deal with dangerous criminals,” Zavala said.

According to records with the El Paso County Historical Society, the first policewomen in El Paso appointed in 1913 were Mrs. C.A. Hooper, Mrs. L.P. Jones, and Juliet Barlow. Jones had a background in charity work for the city and Barlow had a professional medical history, working as a nurse in pediatrics. They were responsible for enforcing sanitation laws and conducting arrests for cases of abuse. In 1917, Lola Eighmey was hired and assigned to work as a traveler’s aid for the YWCA at the union depot.

In 1918 positions for policewomen were eliminated in El Paso, but restored again in 1919 when Julia Kate Farnham was appointed, followed by Virginia Mendez who, it was noted, spoke Spanish.

Farnham and Mendez were assigned to work together and patrol the streets. Mendez was known as a “gun-toting, badge-wearing policewoman,” according to the historical society article which also notes Mendez “was said to be tough and as strong as any policeman.”

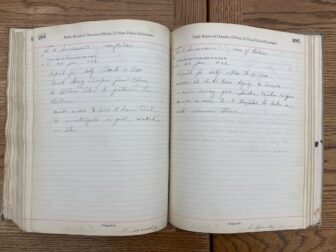

Virginia Mendez, an El Paso policewoman, wrote what she did for every shift she took up in her logbook. Photo credit: Nicole Lopez

Mendez wrote in her logbook for every shift. In the logbook, which is in the C. L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department of the UTEP library, most of her notes read “worked on the streets” or “located a runaway girl.”

Farnham experienced similar encounters. In an April 24,1923 article in the El Paso Herald-Post, Farnham talked about how she would always try to help young girls before having to put them in jail. .Farnham said she felt she was more of an influence to these girls than their parents because they “feared her authority.” She said she believed their mothers were too modern and liberal in raising their daughters.

“Because mothers have not been careful in training their daughters, I find the girls reeling as they cross they Juarez bridge at midnight.”

The policewomen positions were eliminated again in 1923. Mendez went on to serve as deputy county probation office and Farnham took up a job as matron at Washington Park. After that position was eliminated she ran the Upson Hotel, a boarding house on Upson Street.

In 1929, Callie Fairley became the first woman police detective, according to a post on the El Paso History Museum’s Digie site, credited to the El Paso Police Department. She was a detective on the vice squad for more than 25 years and was responsible for more than 96% of arrests involving female vice violators from 1929 until her retirement in 1952.

The post said she “was in charge of handling all woman prisoners confined in the city jail and carry out investigations of woman involved in prostitution and other similar offenses.”

In 1942, according to the EPPD’s annual report, the department began a regular advertising campaign encouraging women to apply as full-duty policewomen.

In its 1947 annual report, the EPPD included a section called “Report of Policewoman.” It listed that women officers investigated 352 clinical cases, arrested 44 juveniles and 717 women.

By the 1950s, police departments began to consider women officers for the same work as male officers, according to research published by Carol Archbold, a professor at North Dakota State University, and Dorothy M. Schulz, a professor at the City University of New York, in 2012. That’s when women all over the nation were being assigned to take on more cases besides sexual and domestic crimes.

Although women are now provided with more and more opportunities, the police force in El Paso is still predominantly comprised of male officers. In 2019, 14% of the 1,153 person police force was made up of female officers, according to an annual report released by the EPPD.

There are five regional commands and the specialty unit in the El Paso Police Department, where female officers are distributed throughout each of these sectors.

“When you’re spread out that far, there are not that many females in any one regional command, so we’re still very small in terms of females,” said EPPD Assistant Police Chief Zina Silva.

Silva, the highest ranking woman in the El Paso Police Department, began serving with EPPD in 1995. Originally from New York, Silva moved to El Paso in the early nineties to continue her powerlifting training with a good friend of hers who was living in El Paso at the time. She was looking for a policing position since the late 1980s. The New York Police Department honored her a role to work in the mass transit subway system, but due to a hiring freeze, she wasn’t able to move into city policing there.

After a while, she decided she would try to pursue an official position as a police officer at the El Paso Police Department.

“I knew what I wanted, I knew where I wanted to be, and I knew what I wanted to achieve,” Silva said. “I was on a good path and I had the opportunity to work in several departments.”

As an assistant police chief, Silva is in charge of the strategic planning and auxiliary services bureau, where she is responsible for writing policies and procedures for the departments, implementing software, delegating city council presentations, and works in resource management. Silva is also actively working in other sectors such as victims services, radio communications, and volunteer programs.

Assistant Police Chief, Zina Silva, is assigned to work in the funeral committee to honor fallen officers. Silva wears a special uniform when attending funerals.

Silva touches on the kinds of assignments that El Paso policewomen take on today.

“We have women working in crimes against persons where they’re managing homicides,” Silva said. “The field has completely opened up for anybody that has the talent, the expertise, and the willingness to learn these job assignments.”

Zavala, of UTEP’s criminal justice department, said there are plenty of ways that the police force can encourage more women to join and diversify their field of work.

“We need to have a police chief or a sheriff that go out there and seek those types of applicants out there,” Zavala said.

UTEP criminal justice assistant professor, Caitlyn Muniz, notes that most recruiting positions are male officers, which may also pose another roadblock when it comes to hiring women in the police force.

“There is the greater issue of recruiting and then within that, recruiting women specifically and really getting women involved in a time where the field of law enforcement needs a positive change,” Muniz said.