It was the end of the Vietnam War and many soldiers were on their way back home. Many were coming back with the after effects of war – PTSD, depression and physical disabilities – to a country that didn’t yet understand how to address such things.

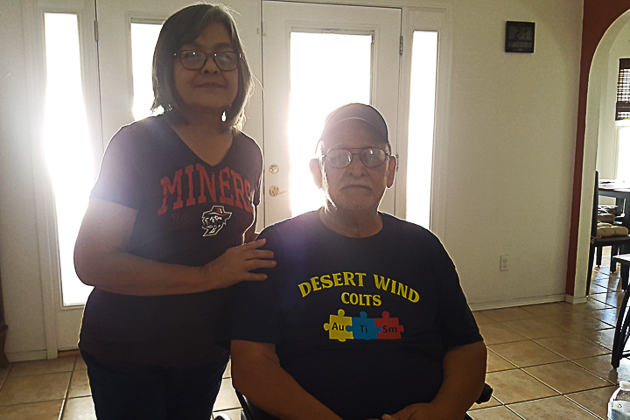

Spec. Rafael Hernando III said he was advised not to wear his uniform as he returned home to El Paso, but he refused to do so. He thought about how much it meant for him to serve, and the price he paid for it with the loss of his legs from a landmine. Hernando spent his early years in South El Paso, then he moved to Ysleta where he went to middle and high school. Hernando, 18 and just graduated from high school volunteered to go to Vietnam. Coming back into the city without his uniform on was not an option.

He knew life would be different, and he was ready for a whole new fight back at home.

Spec. Hernando was not only readjusting to living with a physical disability but also with post-traumatic stress disorder. As life restarted in El Paso, Spec. Hernando learned that the city had much to improve on for accessibility and services for people with disabilities. He felt he could advocate change for these problems while dealing with his own.

“I got involved with the city in the late 70’s early 80’s with their parks and recreation. I became a member of their advisory committee, in getting their recreation centers more accessible for the disabled” Hernando says.

He was surprised to find resistance to the idea of improving accessibility.

“You would think that everyone was just going to jump in and say “Oh yeah, were going to do this.’ No, it wasn’t the case.”

While persisting in pushing for El Paso recreation centers to become more accessible, Hernando realized many of the wheelchair users in the area were also Vietnam Veterans.

“At the same time I started a wheelchair sports association. The first wheelchair association in El Paso was Vietnam vets, and I think that’s what changed the minds of people and what we were trying to do” Hernando says.

Elias Camacho is president of the Vietnam Veterans chapter 844 in El Paso, which has more than 110 members. He said most of them who volunteered to serve.

Camacho says PTSD it was something that wasn’t really understood.

“At the time people didn’t really know what it was…a lot of the people didn’t want to say ‘I don’t feel right, I’m seeing things, I keep feeling things.’ There’s still a lot of Vietnam Veterans with PTSD that have never gone to get mental help and they’ve dealt with it the best they can” Camacho says.

Hernando had his own way of trying to manage his PTSD. He started doing volunteer work talking to children in schools in El Paso.

“I would go to the schools and talk to the kids about the Vietnam War, why it is important because if I didn’t tell them, then who would? I also tell them why its up to them to grow up and make difference in the world and community” Hernando says.

Hernando says he found comfort in the presence of the students. After witnessing the atrocities of war, the children gave him a fresh outlook on life.

“Working with kids, they don’t judge you like adults do. They just look at you and if your real, they’re going to know it. Kids just take you for who you are right instantly after you meet them” Hernando says.

In August of 2009, Socorro Independent School District named a school in his honor – Spec. Rafael Hernando III Middle School. After the school opened, Spec. Hernando found himself doing more public speaking events and spending time talking with even more students.

Daniel Gurany, now principal at Riverside High School, was principal at Spec. Rafael Hernando III schoool when it opened.

“He was picked because of his service and his service in the community,” Gurany says.

To this day, Spec. Hernando can’t believe he received such an honor, but is thankful for the SISD board of trustees for choosing him.

“It was a unanimous vote and I thought ‘Wow, how did I get to impress people like that?’ Never realizing that maybe as you go in life people are noticing what you’re doing,” Hernando says.

Spec. Hernando now spends majority of his time now at home with his wife and visiting with his daughter, who teaches on the West side.

According to the U.S. Census, 17% of El Pasos’ population is made up of Vietnam Veterans and 36% of the city’s population are disabled veterans.