A federal judge has given the government and American Civil Liberties Union until Thursday to develop a plan for reuniting hundreds of children who still haven’t been reunited with their parents weeks or months after being separated at the border.

“The judge is making clear to the government that this must be a collaborative effort and that the government cannot place all the responsibility on the families, especially when it was the government that deported these parents in the first place,” ACLU attorney Lee Gelernt said in a statement.

According to court filings, the government has custody of 431 children whose parents were deported earlier this year without the children they brought with them to the United States. Another 79 children are listed as “adult released to the interior,” and another 94 are listed as “adult location under case file review.”

These 604 children between the ages of 5 and 17 are among the 711 declared “ineligible” for reunification last week as the government declared that it had complied with an order by U.S. District Judge Dana Sabraw of San Diego to reunite families separated at the border by U.S. Border Patrol agents. The ACLU filed a lawsuit in February that resulted in Sabraw’s reunification order.

During a status conference on Friday, Sabraw said “the government deserves great credit” for its efforts to reunify the parents deemed eligible. But he also said the government “is at fault for losing several hundred parents in the process.” Following another status conference on Monday, Sabraw issued an order telling the parties to have a plan by Thursday to reunite children with deported parents, or children the government has lost track of.

Experts have said reuniting children with deported parents will be particularly challenging because the government doesn’t have mechanisms for tracking people after they’ve been deported. “There’s a very good chance they’re going to be permanently separated,” John Sandweg, acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement in 2013 to 2014, told CNN.

Sabraw’s order was the latest of several developments since his deadline on Thursday to reunite families.

Late Saturday, the ACLU filed an affidavit from a volunteer lawyer working with the Annunciation House Legal Project in the El Paso area who said parents were being coerced by ICE into signing a form that said they wished to be deported with their children.

The affidavit said the forms presented three options:

- I want to be deported with my child

- I do not want my child to be deported with me if I lose my case

- I want to speak to a lawyer before deciding what to do.

The affidavit said the first option was pre-checked when the forms were handed out on a bus shortly after several parents and children were reunited on Thursday at the ICE detention facility in El Paso. Several parents said they wanted to choose the second option, and were yelled at by ICE agents, according the affidavit.

When at least four parents continued to insist that they wanted to be deported without their children so the children could press their own asylum claims in the United States, the parents were taken off the bus and not allowed to say goodbye to their children.

Department of Homeland Security officials didn’t dispute the allegations in a statement to Vox, which first reported on the affidavit. “Asking parents in ICE custody, who are subject to a final order of removal, to make a decision about being removed with or without their children, is part of long-standing policy. For parents who have a final order of removal, and whose children have not received a final order, it is the parent’s decision whether to return with or without their children,” the statement said.

Department of Homeland Security officials didn’t dispute the allegations in a statement to Vox, which first reported on the affidavit. “Asking parents in ICE custody, who are subject to a final order of removal, to make a decision about being removed with or without their children, is part of long-standing policy. For parents who have a final order of removal, and whose children have not received a final order, it is the parent’s decision whether to return with or without their children,” the statement said.

Texas immigration attorneys who say they’ve been working virtually around the clock for the past month to reunite families have said the work will continue well past Sabraw’s deadline.

“It’s not over on Thursday. Nuh-uh. As much as I want it to be, it’s not over,” said Ruby Powers, a private immigration attorney in Houston.

Linda Rivas, the executive director and sole attorney at Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center in El Paso, said: “I think that beyond the reunifications, there’s still trauma in these people’s lives after enduring the separation, as well as those parents who remain detained, and the parents who remain deported, and the children who remain without their parents. The problem is not over yet. I don’t know when the end will be, but I think the damage is irreparable.”

Both Powers and Rivas said the response to the family separation crisis from local communities has been remarkable. Lawyers have volunteered their time to help parents and children, nongovernmental organizations have provided care for newly reunified families, and people have stepped forward to donate clothing, food and money.

“As a person who lived through Harvey last summer, it feels like a hurricane without the water. I feel like everyone is pulling together,” Powers said.

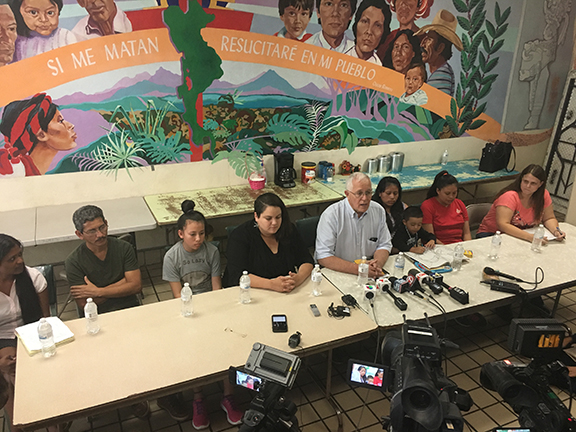

Pressure brought by an outraged public led to the end of family separation and the reunification of most of the 2,600 children taken from their parents, said Ruben Garcia, the founder and director of Annunciation House, an El Paso nonprofit that cared for more than 200 reunited families. That public pressure must continue, he said.

“Historically, as a country we have said we are a country that believes in protecting the vulnerable. I am saying to the American people, let’s not let go of that identity. Let us not lose our moral fabric, our moral integrity,” Garcia said at a news conference on Friday.

Robert Moore is an El Paso-based independent journalist who has been covering the family separation crisis for the Washington Post and Texas Monthly magazine.