EL PASO – The pressure to curb the growing backlog in immigration courts threatens the rights of detained immigrants, especially those seeking asylum, lawyers and immigration judges say.

The Executive Office of Immigration Review recently established completed case quotas for immigration judges to decrease the backlog, but immigration judges say the move will increase the backlog due to potential appeals. Immigration attorneys said this is an effort to speed up the deportation of hundreds of thousands of people.

“Make no mistake, the outcome this administration truly desires from mandating quotas on an understaffed adjudicatory agency with a needlessly overstuffed docket is to transform it into a deportation machine,” said Jeremy McKinney, a North Carolina immigration attorney who is secretary of the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

The move calls for immigration judges to complete at least 700 cases per year, a number that was called unreasonable by immigration judges. Judges and lawyers say the quota system could further clog immigration courts by triggering numerous additional appeals.

The quotas are meant to “encourage efficient and effective case management,” according to a memo by the director of EOIR. Borderzine reached out to the Executive Office of Immigration Review at El Paso for comment but did not receive a response.

The National Association of Immigration Judges say that the quotas only leave judges enough time for a few hours per case.

“Which means that the asylum cases, which often have hundreds of pages worth of supporting documents, hours of testimony, deliberations, the time to issue a decision, all of that is allotted 2 ½ hours from beginning to end. Clearly this is not justice,” said Ashley Tabaddor, an immigration judge and president of the NAIJ.

A U.S. Border Patrol unit drives along the border separating Sunland Park, New Mexico and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Photo credit: Christian Vasquez

About 668,000 cases were pending in the nation’s immigration courts in December, an 11 percent increase since May, according to the Transactional Access Records Clearinghouse at Syracuse University in New York.

Eduardo Beckett, an immigration attorney who is on the Borderland Immigration Council, says the pressure to reduce the backlog come at the cost of due process rights.

“Under the Trump administration, the judges are under the gun to move their dockets faster and not to give you continuance because of strict deadlines, but at what price? The price of violating immigrants due process rights, the right to present witnesses, the right to present evidence,” Beckett said.

“Under the Trump administration, the judges are under the gun to move their dockets faster and not to give you continuance because of strict deadlines, but at what price? The price of violating immigrants due process rights, the right to present witnesses, the right to present evidence,” Beckett said.

For asylum seekers, this means that their lawyers have less time to prepare an application seeking relief from deportation.

Cynthia Lopez, an immigration attorney who specializes in removal defense and family-based petitions in El Paso, said in Otero County Processing Center temporary judges sent last summer by the Trump administration to lighten the backlog were already giving lawyers less time to prepare.

Judges in Otero cut their preparation time in half, and would threaten to issue deportation orders if they did not file an asylum application in time.

“That’s a huge interference with your right to counsel and due process,” said Lopez.

Proving an asylum case is difficult to begin with, Lopez said. Police records, medical records, and statements have to come from another country and be translated into English.

The quotas also create grounds for lawyers to appeal their cases based on due process violations, critics say.

“It’s more incentive to appeal, so even in cases where I have the best grounds for appeal, this alone give me a grounds to appeals on every case that I present,” Lopez said.

The quotas add to an already burdened court system that is trying to keep up with the large increases in funding and reach of enforcement agencies such as Immigrations and Customs Enforcement.

“If you’re running a court like a factory then you’re not really giving out justice, you’re going to cut corners. So to me, this is a recipe for disaster,” Beckett said.

With the new administration, the EOIR has made several changes in the past year that has drawn criticisms from judges and lawyers. Many critics claim that the aim is not to decrease the backlog but to increase deportations.

In January, a memorandum from the Executive Office for Immigration Review required a higher priority for detainee cases in order to decrease the backlog. The memo also removed prosecutorial discretion.

Lopez said prosecutors previously prioritized certain cases, such as those involving immigrants convicted of serious crimes. Now, such discretion has been removed.

The memo said that the discretion “caused confusion” and “did not enhance docket efficiency,” and instituted new performance measures.

One of the measures set a higher priority for detainees to have their case completed. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has a say in who gets detained, said Lopez.

If someone comes to the border seeking asylum, an ICE officer can either detain them or put them on parole, which means they still have to go to immigration court but they are not imprisoned.

“What’s happening here in El Paso, they’re not even reviewing the cases, they’re just saying no, and they’re detaining everybody,” Lopez said.

By detaining everyone seeking asylum at the border and taking away that prosecutorial discretion, the backlog is only going to get worse, according to Lopez.

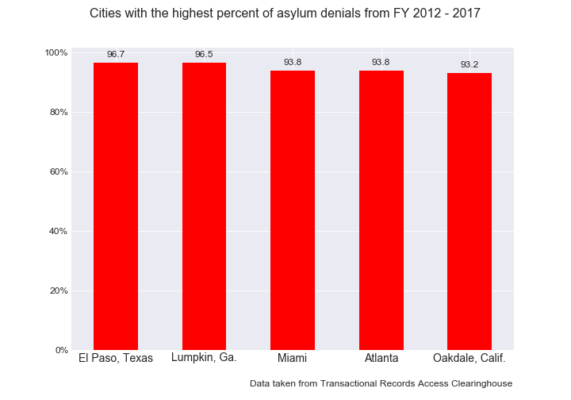

“I just tell (clients) right off the bat, ‘look you are looking at about six months that you are going to be detained, and you have to know that our judges have less than a 5 percent approval rating on asylum cases. Because I want them to know right off the bat and know what they are getting into,” Lopez said.

Ninety-five percent of asylum cases in El Paso were denied in 2017, according to TRAC.

Last summer, another memo was aimed at reducing the number of continuances a judge can give, which lets an immigrant ask for extra time to find an attorney, or allows an attorney to prepare for their clients case. The memo asked that merit cases be only given a continuance in rare circumstances as most individuals are “ample opportunity for preparation time.”

Many detainees do not have access to a lawyer. People in immigration courts don’t have the right to an attorney.

From May to December of last year only 48.2 percent of detainees were represented, according to TRAC.

The data analysis supporting this story has been published as open-source software on GitHub.