I didn’t start to question my identity until my first year of college. Before that I thought I was an American citizen attending kindergarten in Ciudad Juarez. Then in third grade I realized that I was Mexican when I crossed the border to attend Houston Elementary School in El Paso. The first day of school a classmate asked me in Spanish – not English – why I was wearing black polished shoes. I remember I looked around and saw that all the other boys and girls were wearing sporty tennis shoes. My black, narrow shoes were a residue of the strict dress code of the Mexican school I had left behind.

I graduated from El Paso High School in 2012 and the only identity that I identified with was that of a confused young person out in the world.

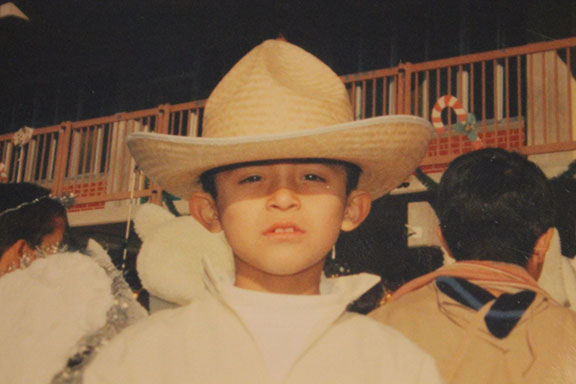

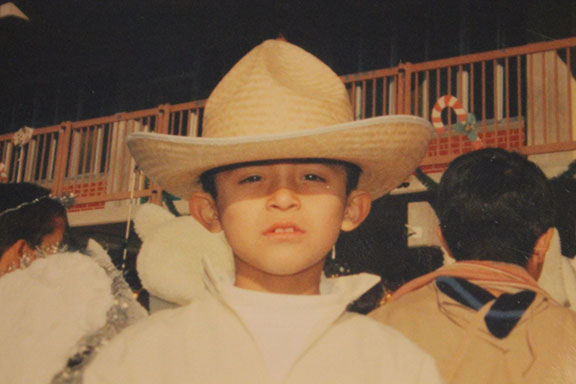

The writer in Ciudad Juarez at age six dressed as a Mariachi for a school carnival.

I wasn’t thinking of my Mexican heritage or my American upbringing until I entered college and read three books my freshman year that challenged me to think about my identity and to pay attention. These books were Drink Cultura by Jose Antonio Burciaga, Pedro Paramo by Juan Rulfo, and On the Road by Jack Kerouac.

First, Drink Cultura suggested that I was a Chicano. Burciaga says that a Chicano is anyone born of Mexican ancestry in the United States. This identity fit me like a glove. I was born in the United States and my formative years were spent in the United States, but I was not entirely American. My mind worked in Spanish, my accent was so thick that sometimes I’d bite my tongue, and I used tortillas to scoop up my food instead of a fork.

But I was not entirely Mexican either. I didn’t know Juarez as well as I know El Paso and some Mexican idiosyncrasies were foreign to me. The tear between my two identities felt reconciled within the Chicano label. It was a third option that rejected both U.S. and Mexican as singular identities and offered the best of both.

Then I read Pedro Paramo, a classic of Mexican literature and I was overwhelmed with cultural pride for my motherland. Pedro Paramo is the story of Comala, a ghost town cursed by its cacique. This book reconnected me with my roots. I looked fondly on my great grandparents from Zacatecas, my grandmother from Durango, my Bracero grandfather, my blonde great-grandfather with green eyes from Chihuahua, and on my Mexican-born parents. It was OK to feel Mexican. The language and the imagery of the book weren’t foreign, they were familiar, like re-reading a favorite bedtime story from childhood. But I still I couldn’t say, “soy Mexicano.”

Finally, Jack Kerouac’s rambling and traveling across the U.S. made me proud to be an American. The life style of the beat generation – the jazz, the booze, the cross-country drive – was as sweet as apple pie. I could personally relate to the book. Before attending college, I’d already taken a couple of short road trips to Albuquerque, NM and far West Texas with friends and there’s nothing more American than discovering new regions of the country. Although Kerouac was white and wrote about his travels to New York, Denver, and San Francisco I related to him and felt a need to emulate his adventures. I wanted to be just as free, but not as drunk.

At the end of my freshman year I was still struggling with the issue of identity. I didn’t fit neatly into just one label – Mexicano, Chicano, Americano. I am not “Mexican” because I lived there for just part of my childhood. I am not a “Chicano” because I cannot relate to the movement or to its culture. I was born in El Paso and attended schools in the U.S. after third grade. My first kiss and first taste of beer happened in El Paso.

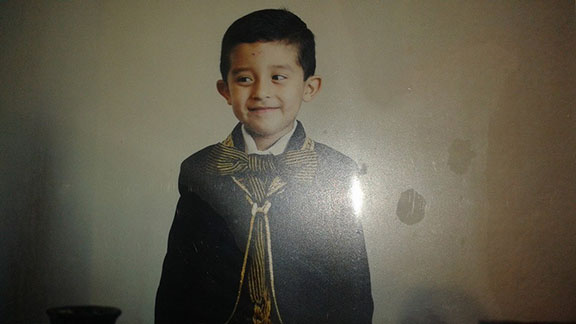

The writer, age 7, wearing the outfit of a Huasteco from a region in Veracruz.

It turns out I’m not the only one juggling identities. According to the Pew Research Center, most Mexican Immigrants consider themselves Mexican, with only 3 percent identifying as American. And 69 percent say they consider themselves “very different” Americans. Surprisingly enough, 32 percent of third-generation Mexican-Americans identify as Mexican.

Adding to the complexity, I am currently dating a Mexican national and her parents call me a “pocho.” To them the word means someone born in Mexico or of Mexican descent who grew up in the United States. This word, considered offensive by some, has a long history. Burciaga says that pocho means “spoiled fruit,” and is often used as a pejorative term. Sometimes the word has been used by my Juarez-born friends to set me apart. Compared to them, I am not Mexican enough. I don’t take the label “pocho” lightly.

A while back my girlfriend and I were hanging out with her cousin and her boyfriend. The conversation turned to the subject of identity and became an argument about how a couple of family visits to Juarez and a fair knowledge of the Spanish language doesn’t make one Mexican. The boyfriend, a third-generation Mexican-American, argued that when he worked in Colorado and parts of Texas he has been called “Mexican” by some U.S. citizens.

This is a common situation facing Mexican-Americans. Mexican-born persons tell us we’re not Mexican enough and there are U.S. citizens that tell us we’re not American enough. These accusations leave us stranded, stuck in the middle of the Rio Grande.

My girlfriend concluded that people of Mexican descent living in the U.S. should fight for the right to be considered “American.”

I agree. As a Mexican-American I acknowledge my Mexican ancestry and my American identity. This is a nation of immigrants, for immigrants and of immigrants.

To those that still struggle with the issue of identity I say that nationality or citizenship doesn’t quite cover all of who we are. In addition to being Mexican-American, I am a fan of British culture. I love their literature and history and if I could be born again, I’d want to be born somewhere in Great Britain. That too is part of my identity.

A human being is more than his or her daily activities. A person is more than his or her taste in food. A person is more than the country where they were born.

Labels we give ourselves or are placed on us by others divide us from others. They imprison us in tiny spaces where we fight among ourselves about who is who or what and what it means to belong.

As a Mexican-American I am more than my citizenship or my family’s heritage. I am an Anglophile that roots for the German national football team. I am a Texan that would much rather be a Californian. I am a journalism student and a writer of fiction. There aren’t enough labels in the world to define who we are.