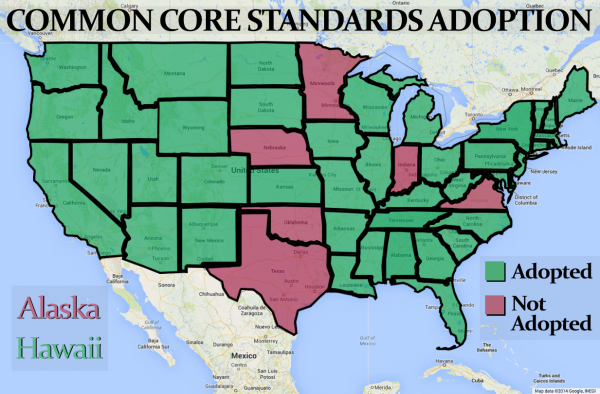

Forty-two states decided to use Common Core standards, starting in 2009 and 2010. Out of those states, many have chosen to join assessment consortium, which provide online testing related to the standards. For some rural schools, administering the online version isn’t easy. (SHFWire graphic by Gavin Stern)

WASHINGTON – It’s a takeover of public education by the federal government. It’s not rigorous enough. It’s too rigorous. It’s not developmentally appropriate. It’ll require schools to collect data about students, including political and religious affiliations. Retina scans of students may even be collected.

It’s Common Core, a program developed by governors and educators to raise education achievement from elementary grades through high school.

After a wonky start, the standards, adopted by 42 states and the District of Columbia, have caused quite the controversy. But for rural schools, the standards raise a more prosaic concern: how to administer tests.

The majority of states that have adopted Common Core have either joined the Smarter Balanced or Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers consortiums, both of which provide online tests related to the standards.

But some schools, especially in rural areas, lack the resources to give the tests.

“We still have a number of small rural districts who do not have broadband access,” Terry Holliday, Kentucky commissioner of education, said.

Lee County, about 75 miles southeast of Lexington, is one of two counties in Kentucky that doesn’t have Internet access.

The state board of education helped the school district get broadband, but the students take paper tests because of a lack of computers.

While Kentucky developed its own tests when it adopted Common Core in 2010, its rural districts have faced similar technology problems that other schools are facing as they attempt to roll out the new online assessments.

“We need adequate bandwidth, so that when we have 50, 60, 70 kids taking the test at once, our system doesn’t crash,” Kendra Anderson, northeast Colorado Board of Cooperative Education Services special projects director, said.

Anderson works with rural schools in Colorado. The state will begin Common Core testing in spring 2015, but Anderson said the state’s schools aren’t ready.

Especially in rural schools, this is because of lack of time, training and funding.

Rob Sanders, Buffalo School District superintendent, has experienced these problems first hand.

The schools he supervises in Merino, Colo., about 110 miles northeast of Denver, teach 318 students in grades K-12. The schools have been using eight-year-old computers and have had to dip into their reserves to update equipment. The district has already invested $45,000 in technology and still has to replace its high school computer lab.

At Merino’s elementary school, the computer lab doubles as a library, so when tests are being taken, students aren’t able to check out books. Because the Common Core tests are long, access to the library will decrease even more this school year. Anderson said 60 days would be spent testing in the spring in Colorado. While it won’t be all day or for every child, it will still take significant time away from teaching.

Not all rural schools have faced technology problems.

The Winner School District in South Dakota, which teaches 676 students in grades K-12, was part of Smarter Balanced field test for its assessment in 2014, and Superintendent Bruce Carrier said things went smoothly.

“We’re lucky that technology-wise, we’re in real good shape,” he said.

Winner is about 90 miles south of Pierre.

At Winner’s high school, all students have laptops. Computer labs and computer carts are available for students at the middle and elementary school.

Mary Stadick Smith, director of operation and information for the South Dakota Department of Education, said a few years ago the governor invested in technology for its school districts. The state provides email and website hosting services, in addition to other technological support for its schools.

In the meantime, Kentucky’s funding for technology has declined in recent years, John Profitt, chief information officer for Lee County school district, said. This hit rural districts the hardest because they have less revenue from taxes.

Since some schools are unable to administer online tests, the Common Core test consortiums will provide paper tests for a limited time while districts build their infrastructure.

But Sanders said students who don’t take the online version are put at a disadvantage.

“It’s kind of like when our original state test for high school math started allowing students to use a calculator on the test,” he said. “Some kids couldn’t afford calculators.”

It’s unfair, for example, if students are given the option to watch a video about an event for the online test version versus reading about that same event in the paper version, he said.

Still, Sanders is not against the Common Core standards, and neither is Anderson.

They’re just against the tests and the way things have been rushed.

“I do like the Common Core,” Anderson said. “I just wish all of our students and teachers could have everything they need to reach the standards.”

_____

Editor’s note: This story was previously published on Scripps Howard Foundation Wire. Reproduced under their guidelines.