By Lindsey Anderson

As part of his school day routine, Daniel Cebreros, 5, gets his Ben 10 Alien Force backpack checked by a Customs and Border Protection agent at the Columbus Port of Entry before heading to Columbus Elementary School. Daniel is one of more than 300 U.S. children living in Mexico who attend public school in southern New Mexico. (Robin Zielinski — Sun-News)

COLUMBUS, N.M. — The sun hasn’t yet risen when the first children arrive.

Most are middle and high school students, beginning the bleary-eyed walk just after 6 a.m. Then come the youngsters, the elementary school children, accompanied by mothers and fathers and tías and tíos.

The families walk through the opening in the wall, running indefinitely in either direction, and up to a small patio and the Columbus Port of Entry.

The parents help their students slip on backpacks, zip up coats and plant kisses on little cheeks, then they send their children off to the United States of America.

Anahi Martinez, 7, gives her mother Amanda Martinez a kiss goodbye under the Columbus Port of Entry canopy before entering the building to cross into the United States for school. (Robin Zielinski – Sun-News)

More than 300 young U.S. citizens living in and around Palomas, Mexico, cross into the United States each day to attend public school in southwestern New Mexico’s Luna County. The arrangement goes back to the 1950s, long before the drug war and the recent immigration debate. But decades-old problems remain.

Though the children are U.S. citizens, born in the nearest hospital in Deming, N.M., their parents are not.

There are no meet-the-teacher nights for these moms and dads. No parent-teacher conferences. No career days or visits to the principal’s office. There is just the wall and the U.S. port of entry, where they wave their children goodbye in the February cold.

To bridge the border and connect with parents, Columbus Elementary School staff are turning to 21st century technologies like Skype. Computers and data-collection also play a role in the classrooms, where educators struggle to overcome language, environmental and opportunity gaps as well.

The morning walk

Schoolchildren cross from Mexico into the United States every day, but most attend private schools and few ports see as many students cross as Columbus, state and national officials say.

The students make up nearly half of the 800 pedestrians who cross each day at the state’s only 24-hour port.

“We’re just kinda a unique port because we have so many kids,” Port Director Robert Reza said.

U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan agreed: “I go to so many schools, and this one is a different one for me,” he said during a visit to Columbus Elementary last fall.

The school is less than 10 minutes from the U.S. border, in a town of 1,600 that Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa attacked in 1916. Ninety miles west is Arizona. Palomas, with nearly 5,000 people, sits just across the wall.

Dad Domingo Acosta gets up at 5:10 a.m. to get his children to the port by 6:20 a.m. Some mornings, the pedestrian line stretches to the wall and children miss the bus. On those days, the kids return home, he said as he watched his children file through the day’s unusually short queue.

The young crossers are treated like anyone else passing through the port, Reza said.

“There’s really nothing out of the ordinary except that they’re school kids,” he said.

Those with a passport card get in an expedited line. Those under 16 years old can bring copies of their birth certificates, often laminated documents that bear the creases of being folded again and again in their hands.

Customs and Border Protection officers ask the students’ names, ages, where they were born. They ask again and again: “¿Cómo te llamas? — What is your name?” “¿Cuántos años tienes? — How old are you?”

Most of the student’s Disney princess and superhero backpacks are then searched. Sometimes the officer flips through a book or asks a student to unzip a puffy jacket.

On this day, only two red apples were confiscated under agricultural laws, though an agent thought she smelled something as a student passed, sniffing his shoulder before determining it was nothing.

The children file through the port and onto bright yellow buses on the other side, elementary schoolers headed into Columbus and older students going 30 minutes north to Deming.

“Parents trust us with their children and they don’t even know what we look like,” Columbus Elementary Principal Armando Chavez said.

Former port director Joseph Rivera, now a substitute teacher for the Deming school district, assists students Iris Carbajal, 11, left, and Viviana Ramirez, 11, onto the school bus after they crossed the U.S.-Mexico border. (Robin Zielinski – Sun-News)

Bridging the border

School district staff are not allowed to cross into Mexico for work, and phones are a “hit or miss” with Palomas parents, Chavez said. School staff often aren’t notified when phone numbers change, and email is out of the question while Internet penetration remains slim across the border.

Skype helps fill that communication gap.

Columbus Elementary dual-language teacher Ricardo Gutierrez owns a restaurant in Palomas. So last May, the school held a conference with parents at his restaurant via video chat. About 80 Palomas families gathered around a TV for the one-hour group meeting.

The school expanded the technology further in January, holding individual 10-minute parent-teacher conferences via Skype. Educators filled more than 80 parents in on their students’ behavior, progress, homework and more.

“In order for us to help the child, not only with academics but with any problem the child is coming to school with, we must be in a constant communication and become a team: the teacher, myself and the parent,” Chavez said. “… A lot of times, the parent is the missing link.”

He hopes to expand the technology further next year, devoting a morning or afternoon to video conferences each week.

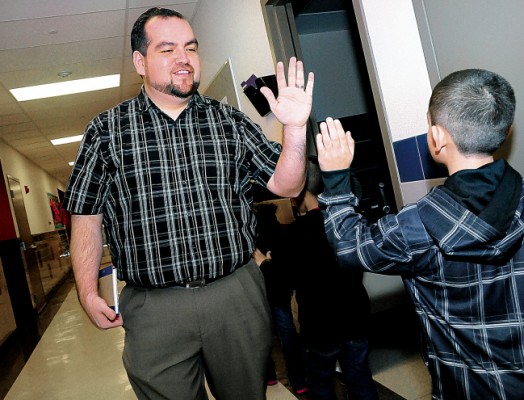

Columbus Elementary School Principal Armando Chavez high-fives students in the school hallway as they change classes. (Robin Zielinski – Sun-News)

A gap remains

Skype bridges some divides, but not all.

The state gave Columbus Elementary an “F” grade two years in a row.

Just 32 percent of students tested proficient in reading and 33 percent proficient in math last year, according to state data.

The school faces similar challenges as others across southern New Mexico: Nearly all students — whether they live in Mexico or the United States — receive free or reduced-price lunches. Most are English language learners.

Yet many Palomas students begin kindergarten having never held a pencil or a pair of scissors; some have never used an indoor bathroom. They often don’t have books at home and aren’t proficient in Spanish, let alone English, educators say.

“Yet we’re expected for them to perform at the same level as (students) throughout the state,” said Columbus reading interventionist Glenda Sanchez, a former kindergarten teacher.

Daniel Bailon, 6, drinks his milk in a classroom at Columbus Elementary. Nearly all students at the school receive free and reduced-price breakfasts and lunches. (Robin Zielinski – Sun-News)

Surviving violence

For years, children also endured brutal drug-related violence in Palomas, two hours from Ciudad Juárez.

Homicides have dropped significantly in the Mexican state of Chihuahua since the peak of the drug war in 2010. But children witnessed that violence on their way to the port each day, passing three severed heads in the placita or their uncle fatally shot in his pickup truck. Some lost parents or had their homes hit with grenades when they were away.

There were discipline issues during those years, administrators said.

“They saw so much when the cartels were just at their max,” Sanchez said. “… Kids start to see it as normal.”

As the violence ebbs, marijuana continues to flow through the Columbus port.

“We really have not seen a decrease in smuggling,” Reza said.

He estimated in 2012 that 40 percent of drug smugglers are children. Some are as young as 14, carrying the load in their backpacks during the morning crossing.

Former Port Director Joseph Rivera, now a substitute teacher for the school district, said kids have always carried drugs across the border.

“It’s just become more prevalent because the profit margin is ridiculous,” he said while guiding Palomas children onto a waiting yellow school bus.

Columbus Elementary School teacher Lourdes Espinoza goes over dictation exercises with her fourth grade dual-language class. Espinoza was a Palomas student herself, crossing the U.S.-Mexico border for school each day when the agreement permitted Mexican students to attend school in New Mexico. (Robin Zielinski – Sun-News)

Changing agreement

Critics say the Palomas children shouldn’t attend U.S. public schools if their parents aren’t paying taxes in the United States. Educators see it differently.

“Do we want them to be American citizens and illiterate?” Deming Superintendent Harvielee Moore said. “No. We want them to be American citizens who can get a job and give back and pay taxes.”

But fewer Chihuahua children are being born in New Mexico after the two states agreed to improve the Palomas medical clinic, once insufficient for most births. Now, only medical emergencies are sent to Deming by ambulance.

The number of births by Mexican residents in Deming has dropped from 89 in 2009 to 31 in 2012, according to the state Department of Health.

New Mexico officials and educators say they will keep teaching whomever comes to their schools.

The state Constitution simply requires public schools to be open to “all the children of school age in the state” regardless of residence.

“If a child shows up at the schoolhouse door, we provide them with an education,” Deputy Education Secretary Paul Aguilar said.

Chavez is intent on raising the quality of that education.

He thinks the school has found the right mix between old-school and new-school technology, between teachers, educators, parents and students. The staff has even established a “war room” dedicated to student data and progress. Colored index cards line the walls, tracking the progress of all 566 students.

“This year,” he said, “we will not be an F school.”

Despite challenges, students come to school each day dressed in their finest and ready to work, Chavez said. Palomas parents instill in them the importance of learning, educators said.

“Look at the time just to get an education,” Chavez said. “And some people don’t understand, they don’t get the big picture of what we’re doing.”

_____

Editor’s note: This story was previously published on Las Cruces Sun-News

A touching story, and one that should be featured in the Grand Parent Daily News, if there were such a newspaper. I will send it on.