By Kay Bárbaro

WASHINGTON — In spite of independent Hollywood producer Phillip Rodríguez’s stated belief that the killing of KMEX-TV (Los Angeles) news director Rubén Salazar 44 years ago was accidental, two separate audiences – in Washington, D.C., and Long Beach, Calif. — that previewed his 54-minute television documentary, beg to differ. Where there was grist for an exposé, a TV rehash resulted, some say.

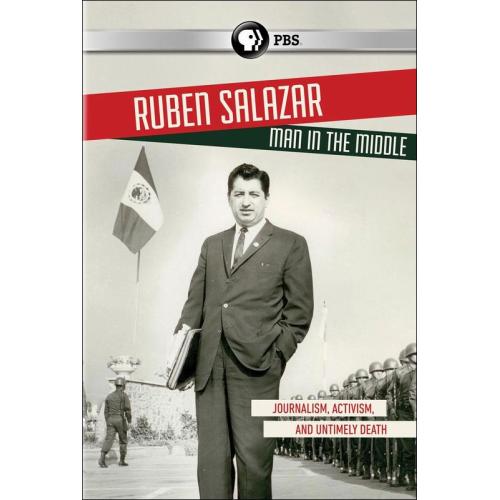

The program — Rubén Salazar: Man in the Middle — is scheduled to run nationally April 29 on the Public Broadcasting Service network.

PBS’ documentary Ruben Salazar: Man in the Middle will be previewed at UTEP on April 9 at the Union Cinema at 6pm.

Responding to PBS invitations, 125 brave souls, including Hispanic Link’s reporter/editor team Aaron Montes/Charlie Ericksen along with Scripps-Howard Journalism Foundation member Peter Copeland ventured into the sub-freezing night of Feb. 27 to view it in the Smithsonian American Art Museum auditorium in northwest Washington, D.C.

On the warmer West Coast, activist/professor Armando Vásquez Ramos hosted a youthful crowd of 350 at California State University, Long Beach’s theater March 10, with 100 guests attending the reception and discussion that followed. Documentary producer Rodríguez was joined at the events by longtime Salazar friend Phil Móntez, who recently retired as West Coast regional director with the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Among other preview showings: Mark April 9 in El Paso, Texas, across the border from Ciudad Juárez, Salazar’s Mexican birthplace. He grew up in El Paso and gained his first reporting job with the daily Herald-Post there. This event, expected to draw another large turnout, is being coordinated by the University of Texas at El Paso Communication Department.

After synopsizing Salazar’s career, including foreign assignments as a Los Angeles Times correspondent in Mexico, Cuba and Vietnam, the documentary brings him back to the states where his beat is narrowed mostly to Mexican Americans and East Los Angeles. Reading the transfer as a demotion, he writes Times managing editor Frank Haven, “The abrupt change now, practically without warning, is professionally defeating and distressing personally. I can’t help but ask: How long is it going to take for me to prove myself to the Times?”

Not too long thereafter, Salazar quits the L.A. Times to become news director of the Spanish-language television station KMEX, but agrees to produce a weekly column for the paper, thus reaching audiences in both languages. Ironically, his freedom to report through his Spanish-language KMEX team and the English-language Times on institutional and police racism that plagued the Mexican-American community, led to his death.

The PBS documentary patches together a batch of interviews with police and other establishment representatives, most of whom conclude that Salazar’s death at age 42 was just “an unfortunate accident.” When producer Rodríguez concurs with their conclusion after the Long Beach showing, Móntez shoots back, “You made a movie. I lived it. I disagree with you.” The crowd applauds and shouts in vigorous support of Móntez’s rebuttal.

Some of the strongest elements in the preview screening surface as Móntez recounts personal interactions with Salazar on how the police try to get Salazar fired, or worse: Six days before the police grenade kills him, Rubén is teased by Phil, “Mexicans need a martyr, let them pop you,” Móntez said. Salazar responded “No, let them pop you! I am better looking than you are.”

Throughout, Móntez challenges certain other speakers’ assumptions. He offers some key balancing context, sometimes without great detail that the coroner’s jury in the case could or would have elicited from him. Móntez had been pressed to testify at the inquest but without explanation, his name was ultimately deleted from the witness list. (Will PBS get around to bleeping him when he exclaims “Bullshit”?)

Link publisher Charlie Ericksen, a U.S. Civil Rights Commission staff member at the time took a call from Salazar at the Commission’s Los Angeles office a week before the KMEX news director was killed. Salazar informed him and elaborated at a meeting with Móntez three days later that the police had a regular tail on him. He spoke of his fears of police retaliation against his coverage of anti-Hispanic police brutality and their killing of two innocent Mexican workers in a downtown L.A. wrong-door raid, July 16, 1970.

Two representatives of the LAPD visited and cautioned Rubén, “This kind of information could be dangerous in the minds of barrio people.” In the documentary, KMEX-TV president Danny Villanueva confirms what he told Ericksen years before: that the Los Angeles police urged him to fire Salazar.

After the documentary was shown at the Smithsonian, Ericksen asked for a show of hands by the 125 people in the audience. “How many of you feel the police were NOT complicit in the killing of Rubén Salazar?”’ Only three hands went up.

In a morning-long filmed interview with producer Rodríguez a couple years prior, Ericksen detailed Salazar’s reason for concern. The week before he was killed, Salazar told Ericksen he wanted it on the record with federal authorities that the cops were out to get him. Eight days later he became the first of only two fatalities among 30,000 Latinos at the anti-Vietnam War demonstration. Ericksen has maintained all along that contrary to the coroner’s explanation, Salazar’s death was no accident.

He remembers pointing out to Rodríguez, as he had done in other interviews, that while Rubén was a dedicated journalist on the job he left that passion at the office. To his now-deceased Anglo wife, Sally, whom Ericksen knew prior to her meeting Rubén, and to the Salazars’ three children, Rubén was 100% husband and daddy.

Ericksen remains upset by his only 23 words that Rodríguez chose to use to encapsulate their morning-long interview at Hispanic Link in Washington, D.C., a couple years earlier. Rodríguez ignores Salazar’s prophetic call and in isolation, fails to reflect Sally’s complete devotion to her Mexican-American husband. The only words quoted: “He (Salazar) did lead a very separate life at home as he did a journalist. His wife Sally never adapted to any Hispanic culture.”

In 1980, on the tenth anniversary of Rubén’s death, Ericksen teamed as editor with Sally when for the first time she reflected on her husband’s eerie premonitions about his fate.

Past KMEX-TV president, Danny Villanueva concludes, “They opened Watergate. Why wouldn’t they reopen this.”

(Kay Bárbaro, phonetically in Spanish ¡Qué bárbaro! (How barbaric!), is a byline pseudonym for some opinion pieces to which various Hispanic Link News Service staffers contributed. Editor Ericksen and reporter Aaron Móntes did the major research and writing for this article. Reach either at 202-234-0280 or at hispaniclink.org)