Esperanza with grandchildren Evan Miller and Trinity McClain. (Photo courtesy of Esperanza Joseph)

Loyalty goes a long way for Greeneville woman

By O.J. Early

A visitor to the kitchen of Esperanza Joseph will likely find her leaning over a counter, arms caked in cornmeal, preparing tamales, perhaps for an event at her church.

Joseph, 65, has been serving up tamales, and various other authentic Mexican dishes, since her childhood, using her cooking talents as one of many means to become an active community member.

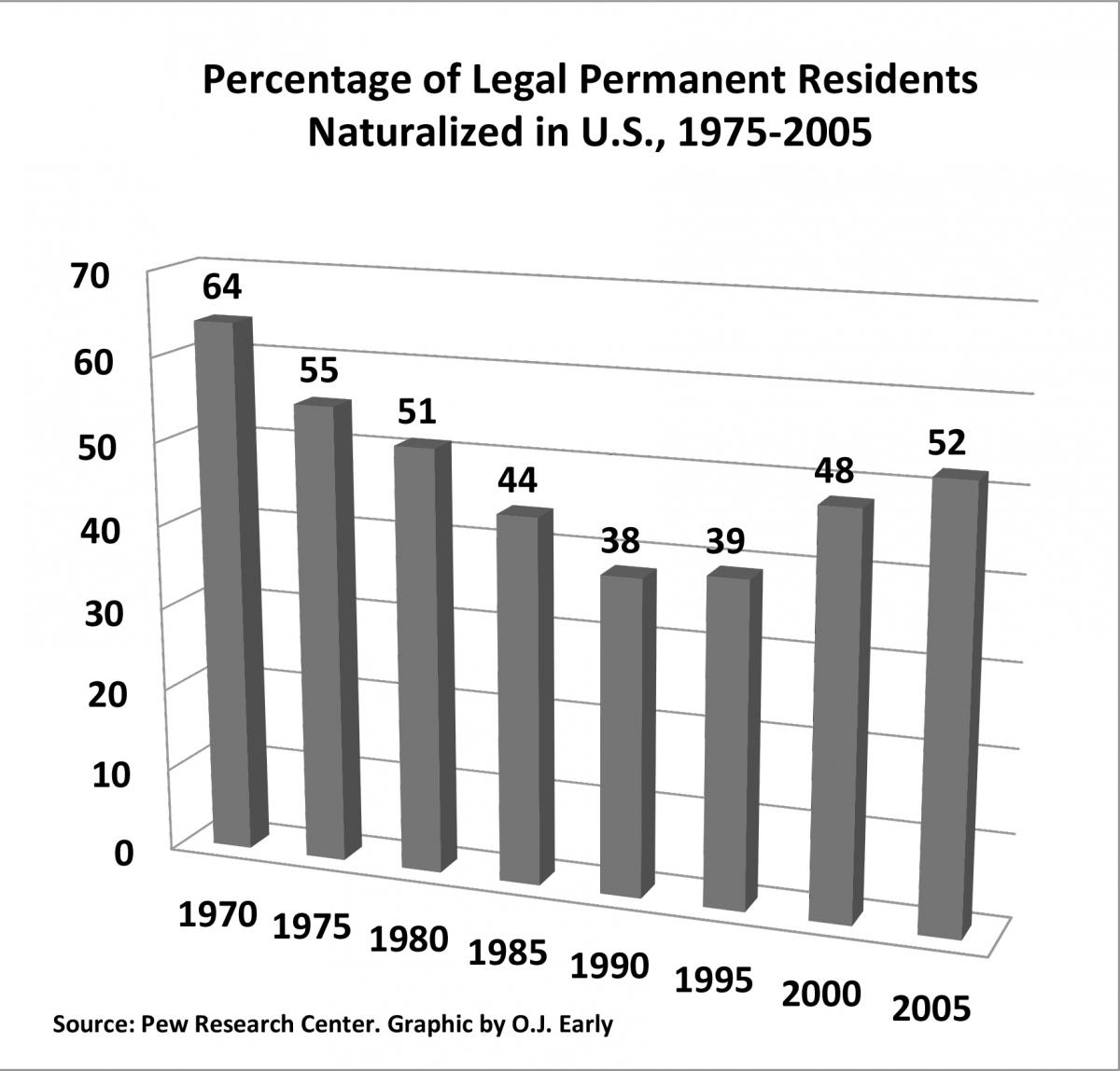

She has lived in Greeneville, Tenn. since the 1980s and has been in the U.S. for more than 40 years. And for at least the last two decades, Joseph has been bucking a nationwide trend – sort of.

Esperanza Joseph prepares one of her favorite dishes, tamales. (O.J. Early/El Nuevo Tennessean)

Joseph, a Mexican citizen from the state of Chihuahua, is officially recognized in the United States as a permanent resident alien – legal immigrants who choose to remain citizens of their native country while living, on a permanent basis, in the U.S. Nationwide, the number of permanent residents aliens is in decline.

For Joseph, the reasons for doing so aren’t complex: She holds a deeply embedded patriotism for her native country while maintaining a solemn respect for America.

“I love both countries,” said Joseph, sitting in her kitchen, surrounded by cooking magazines and utensils. “To me, it doesn’t make any difference. To me, people had been treating me so nice. I didn’t see the need.”

In a 2011 study released by the Pew Research Project, a little more than one-third of all Hispanics living legally in the United States were foreign born.

In a 2007 study, also conducted by the Pew, 52 percentof foreign-born residents in the United States chose to become citizens – the highest-ever percentage of foreign-born residents choosing citizenship.

Though the number of Hispanics electing to become U.S. citizens has risen considerably since 1990, Mexican-born immigrants, like Joseph, are still the least likely of any immigrant group to naturalize – a trend well-established for decades, according to the report.

(O.J. Early/El Nuevo Tennessean)

Reasons given by immigrants who don’t seek U.S. citizenship, according to the report, range from loyalty to one’s home country to the amount of time it takes to become a U.S. citizen.

“The Hispanic culture in general is a patriotic one,” said Holly Melendez, a Spanish instructor and former Hispanic community liaison at East Tennessee State University. “There are strong roots and often family members remaining in other countries.”

Patriotism for an immigrant’s home country is likely the chief reason that American citizenship isn’t chosen, Melendez said. Other reasons include the cost and level of difficulty of becoming a citizen, she said.

“I personally know people who have lived here for many years and plan to live here for many more as they work and support families, but intend to return ‘home’ upon retirement,” Melendez said.

“It’s a personal decision, and while some people are very anxious for citizenship and all of the rights and benefits associated with it, others prefer to remain here only as guests.”

Joseph first came to the United States at 12, attending a Catholic school in El Paso, Texas with cousins who lived in the city. It was there she began to learn English.

In El Paso, she would travel frequently back to Mexico, something she did for most of her teenage life.

Upon graduating, a family friend – whom she called “Aunt Lucy” – invited her to stay in El Paso. Joseph, 18 at the time, accepted her offer and worked as a cook at a local club – one she described as very friendly – cooking Mexican dishes for soldiers stationed at nearby Fort Bliss.

“I was like her daughter,” Joseph said of her “Aunt Lucy,” with whom she stayed for four years.

And it was while working in El Paso that she met her future husband, a soldier stationed at Fort Bliss. The courtship took off, and Thomas Joseph asked his future wife to marry him after one month of dating.

“How can you love someone so soon?” she recalled asking her then-fiancé. His reply: “When you meet someone that’s good like you, you have to appreciate that and be happy.”

The two married in 1969, and moved immediately to Houston, where they lived for 13 years. In Houston, the couple had all three of their now-grown children.

A flurry of events brought the Joseph family to East Tennessee in 1983. The main reason, Joseph said, was her husband’s family living in neighboring Kentucky and the opportunity for Thomas to get a new job.

“We came here because he didn’t like Kentucky that much to raise a family there,” she said with a laugh. “I fell in love with the mountains and the pines and the trees. Chihuahua is like that. It reminded me of home.”

Joseph still easily recalls that while living in Houston, she was only a few blocks from an American consulate.

“’Come down here and you can become an American citizen,’” Joseph recalled workers from the consulate telling her. “But I never did.”

She also remembers a man who she described as rude and mean incorrectly explaining to her that she must step on the Mexican flag to become a citizen of the U.S.

“My husband got very angry,” she said. “My husband said, ‘She become an American citizen if she wants to. I support her, I sponsor her. I am her husband.”

In fact, Joseph said, her husband has always supported her decision to remain a citizen of her native country.

While Joseph recognizes that some benefits would be hers if she became a U.S. citizen, she is content in keeping her citizenship in Mexico.

Since coming to Greeneville, Joseph’s community involvement, both as a volunteer and employee, has been extensive.

“She is a very helpful person and she likes to help the community a lot,” said Joseph’s son, Thomas, a student at the University of Tennessee. “She likes to help in the community, contribute to churches, charities, things like that.”

After adopting Greeneville as her home, Joseph has worked as a substitute Spanish teacher at two local high schools, served as a translator for the county’s jail and for two local judges and worked as a cook for local restaurants, in addition to extensively volunteering at her church, Notre Dame.

“The reason I started working (at a local restaurant) is because everybody wanted me to,” she said with a smile. “When I first came here, not even Taco Bell was here in Greeneville. Everybody – lawyers, doctors, police officers, judges – called me and asked ‘Can you cook for me?’”

You can bet that Joseph, as long as she’s able, will continue to cook and serve in her community.

According to Joseph, being an American citizen matters little in that respect.

_____

Editor’s note: This story was previously published on El Nuevo Tennessean.