Pachuco Zoot: A Tale of Identity by coreographer Lisa Smith. (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

EL PASO – He stood tall and proud next to his newly polished red 1937 Chevy Deluxe Coupe, the feather on his wool felt tonda gliding through the cold spring breeze, his lisa and drapes crisp without fail. The two toned calcos on his feet shined as a star on dark cloudless day.

No one in the barrio had trapos as suaves as this vato.

He is part of the Pachuco subculture of young Mexican-American males that developed in the Southwest during the late 1930’s and early 1940’s. They wore brightly colored zoot suits and spoke in a lyrical blend of Spanish and English called Caló.

On February 10, the University of Texas at El Paso department of theater and dance opened a 10-day production of Pachuco Zoot: A Tale of Identity, a dance theatre piece that celebrates Pachuco culture.

“I love the whole zoot suit culture, I find it to be very unique and overlooked. I specially fascinated with the fact that it originated in the El Paso and Juarez area, which I consider to be my adoptive home,” said Lisa Smith, professor of dance at UTEP and choreographer of Pachuco Zoot.

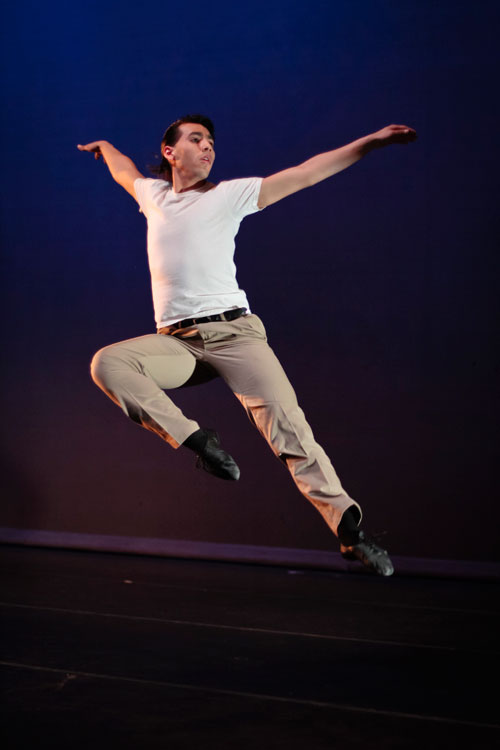

Jose, a young Mexican American who is struggling to find his identity. (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

The ballet tells the story of Jose, a young Mexican American who is struggling to find his identity. The story follows Jose from El Paso’s Segundo Barrio, during the 1940’s, to Los Angeles, California, where he reinvents himself as a Pachuco.

“A lot of research took place in the making of Pachuco Zoot, I wanted to make it as authentic as possible,” said Smith.

“The zoot suit first gains prominence in the Jazz age in the African American community,” said Dr. Frank G. Pérez, chair of the Department of Communication at the University of Texas at El Paso. “It resurfaces as a Chicano wardrobe in El Paso and Juarez.”

The zoot suit was not limited to Pachuco culture. People of all walks of life wore the long and floppy colorful suits. The costume was propelled into prominence with Mexican Americans by the famous Mexican comedian Germán Valdés, known by his stage name Tin-Tan, who sported the zoot suit and spoke in Caló in his films.

During the 1940’s minorities were segregated and marginalized from mainstream society. In cinema, there were few Mexicans. If a Mexican appeared in a film it would be in the role of bad guy often played by a white actor in brown-face.

“Psychologically and sociologically the zoot suit communicated an acknowledgement of being marginalized,” said Pérez. “By wearing the suit, Pachucos displayed that it did not matter to them if they were accepted. The suit portrayed pride in them and in belonging in an ostracized group.”

In June, 1943, Pachucos were branded as antisocial bad guys by the media in Los Angeles. For 10 days the media promoted the idea that Pachucos were goons, punks, anti-American, and a social threat.

Those 10 days were branded the Zoot Suit Riots and the Pachucos were accused of beating up sailors. “Looking at the photographs one can see that when the sailors got off duty they went to East L.A. and started beating up Pachucos, not the other way around,” said Pérez.

The sailors would get into groups, drive into East L.A., locate pachucos, strip them of their clothing, beat them up, and leave them in the street. When the police arrived at the scene they would arrest the Pachuco and charged him with disturbing the peace.

“To strip the suit off a Pachuco was emasculating,” said Pérez.

It was not until the military authorities declared the City of Los Angeles off-limits to military personnel that the riots stopped.

Pérez explained that the reason the zoot suit wearer become a threat to the U.S. psyche was because psychologically the America of that time could not handle the fact that there were Mexican Americans fighting in World War II.

The main character, Jose, is guided by his muse in his identity journey. (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

Actions taken against Pachucos had started a year earlier with the Sleepy Lagoon Murder trial. The body of a young man, Jose Diaz, was found in a reservoir in southeast Los Angeles. Young men, who belonged to the 38th street club, or gang were put on trial. Many where charged with murder, but all convictions where later overturned for misconduct on part of the Judge and the District Attorney.

The Pachuco had become the first contemporary symbol of resistance from the Chicano perspective as well as a symbol of a Mexican threat to the mainstream.

“The discourse of how the Pachuco was viewed overlooks the reality that Mexicans were marginalized. In the 30’s we were repatriated, 1.2 million illegal and legal Mexicans were sent back to Mexico,” said Pérez.

Being part of an ostracized group in a pre-civil rights time meant not many opportunities were available for minorities. Even if Pachucos cleaned up and got an education they were still a minority.

“The Pachuco becomes something that you aspired to be. Many would never have the money to buy a Cadillac, but if they can get and fix an old Chevy, and dress in a good suit, they would have high built status.”

Besides having a nice clothes and a nice car, dancing also carried a lot of social capital. “Dancing and music have always been central to adolescent identity, they were some of the only places Pachucos could channel their skills and talent,” said Perez.

Besides the usual library research, Smith asked her students to research Pachuco culture in their own families. “Everyone had a connection and contributed their findings in the development of the ballet,“ said Smith.

“Dancing to a piece like Pachuco Zoot was a great experience for me. The music, the choreography and the speeches in between the piece made me feel like I was part of that era. The music was very upbeat that it made me keep moving and smiling throughout the whole performance,” said Jose Barraza, who played the character Jose.

Smith wanted to produce a dance theater piece about zoot suit culture for many years, but could never get the right mix of performers and resources. For years she kept the idea in the back of her mind until it was time.

“We have had a great response, many people have been coming to see Pachuco Zoot. I feel we have reached a broader audience than in other years,” said Smith.

“They could deny them equality they could marginalize them but they can’t take away their attitude, their look, their style and dance. Style was very crucial for a Pachuco and a way to express it was through dance,” said Pérez.

”It was the secret fantasy of every vato, living in or out of the Pachucada, to put on the zoot suit and play the myth…” – El Pachuco, a character in “Zoot Suit,” a Hollywood film from 1981.

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- Pachuco Zoot: A Tale of Identity by coreographer Lisa Smith. (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- Jose, a young Mexican American who is struggling to find his identity. (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)

- (Ezra Rodriguez/Borderzine.com)