TUCSON, Ariz. – In Arizona, victims of violent crime have access to as much as $20,000 to help pay for funerals and other expenses. But officials and a report by Arizona State University assert that there’s a wide variation in how counties in the state disburse the money.

The study, released in August by Bill Hart, a senior policy analyst at Arizona State University, called the crime victims compensation program “among Arizona’s best-kept secrets.”

(Lazaro Gamio/New York Institute)

According to the report, the total number of claims filed in Arizona by victims seeking compensation decreased 25 percent between 2002 and 2010. In the same period, the number of claims approved decreased 19.5 percent, to 1,238 from 1,538.

“It’s not easy to get compensation,” Hart said. “Either people don’t know about the program or the rules are pretty strict.”

The report outlines a number of factors that have contributed to people’s difficulty in getting compensation, including a lack of awareness of the program and a decentralized system of operations.

Arizona and Colorado are the only two states in the country that have decentralized systems. In Arizona, each of the state’s 15 counties has its own board responsible for the distribution of monetary assistance to crime victims.

“It’s not easy to get compensation when rules are pretty strict and rule interpretation varies by county,” Hart said.

Arizona residents are eligible for compensation if they make a report to police within 72 hours of a crime. They may become ineligible if there is proof that they were involved in the crime itself or if they have outstanding county debts.

Dan Eddy, executive director of the National Association of Crime Victim Compensation Boards, said having a decentralized system encouraged prosecutors to refer local victims to the program.

Critics say decentralized operations can lead to inconsistency in decisions and differences in rules’ interpretation.

“Sometimes board members’ opinions, where they live, culture and bias take part in whether they approve or deny a claim,” said Larry Grubbs, program manager of the Arizona Criminal Justice Commission Crime Victim Services. The commission collects and distributes the funds to each of the 15 counties based on population.

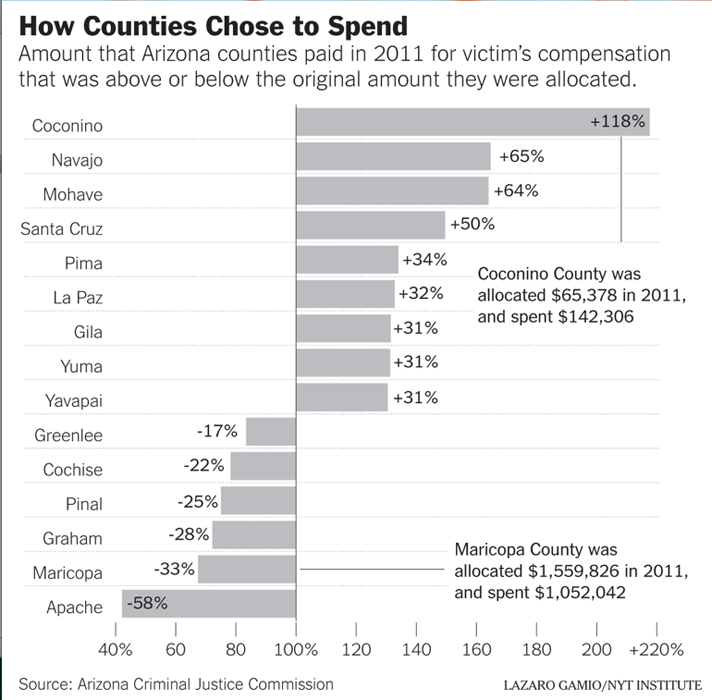

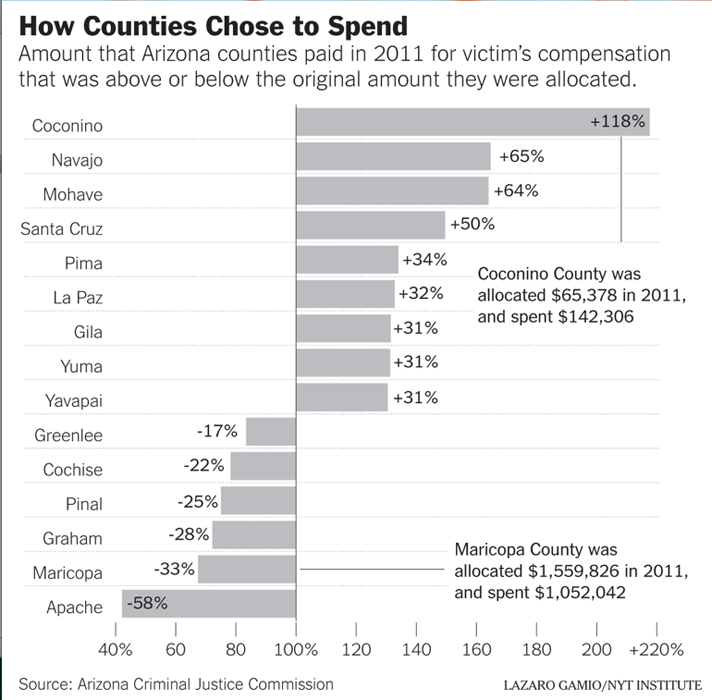

In 2011, the commission allocated $2.8 million for the compensation program, with $2.56 million paid out to compensate 1,761 victims. For 2012, $3.85 million is available to be distributed to victims.

Counties that do not use the funds allotted to the program must return the money to the commission at the end of the year. The money is then redistributed to counties that may have fallen short in funds.

The maximum award for a single claim in Arizona remains among the lowest in the nation, at $20,000. States with some of the highest payments include California, Oregon and Ohio, whose residents are eligible for payments between $50,000 and $65,000.

Arizona receives about $1 million of the total $705 million approved annually by Congress. Federal funds, which come from fines paid by convicted offenders in federal prisons, constitute a third of the compensation budget. Arizona’s remaining two-thirds comes from unclaimed victims’ restitution fees paid by offenders in each county and state attorney general settlements.

According to the Arizona Criminal Justice Commission, many Arizona counties do not spend all the money budgeted for victims’ compensation. Among those is Cochise, a county with 140,263 residents in southern Arizona. In 2011, county officials returned $14,464 of the initial $60,000 they received from the commission.

On average, about 15 percent of applications in Cochise County are rejected before they’re reviewed by the board, for not meeting the initial requirements set forth by the county, said Meg Bokhari, coordinator of the Cochise Victims Compensation Program.

“I know right now we have a lot of money in our account to help people,” Bokhari said. “If they meet the criteria, they will be OK for payment.”

In Maricopa County, which covers Phoenix and is the largest county in Arizona, with a population of 4,023,331, board officials returned $507,784 from the initial $1.37 million allotted by the state commission. The total number of claims filed in the county also dropped, to 611 in 2011 from 745 in 2009, and the number of claims denied increased to 101 in 2010 from 57 in 2007.

Julie Williams, coordinator for the Maricopa County Crime Victims Compensation program, and Jerry Cobb, public information officer for the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office, would not comment on the amount returned to the state or about why filed and approved claims had decreased.

Program coordinators across the state agreed that many Arizona residents do not take advantage of the program because they do not know it is available to them.

In 2009, Santa Cruz, a county in southern Arizona with 47,900 people, began an aggressive outreach effort to increase awareness of the county’s victims’ compensation program.

“My team and I visited schools and hospitals,” said Inti Vasquez, director of Santa Cruz County Victim Services. “We respond on the scene, collect victims’ info and follow up with them to refer them to the program.”

In 2009, claims filed in Santa Cruz increased to 837 from about 200. In three years, payments went from $3,540 to $45,640.

In Apache, a county in northern Arizona with 76,668 residents, program coordinators encouraged local law enforcement agencies to spread the word about the program. As a result, the number of claims filed and payments increased, officials said.

“Those are counties that have recognized a need in the community,” Grubbs said.

The Arizona Criminal Justice Commission has scheduled a session to review the program’s guidelines this year. Officials plan to discuss considering crime rates and yearly payments on fund distribution.

“I believe it is the responsibility of ACJC to develop a formula that is able to effectively allocate to each county program the money they need,” Grubbs said.

_____

Editor’s note: This story was previously published on The New York Times’ Student Journalism Institute Tucson 2012.