SPRINGFIELD, Mass. — Near the end of the evening, when the television cameras were finally turned off, but fans were still clicking photos, Tim Hardaway tried on the orange blazer that all Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductees are gifted.

You could sense right away that the jacket wasn’t his style, and he wouldn’t likely wear it as much as the massive ring. But it fit.

In that moment, he dipped his left shoulder, put an imaginary basketball through his legs and into his left hand, and then changed hands back to his right — it was his iconic killer crossover. I was lucky I didn’t blink or I’d have missed it, it happened that quick. Then he laughed at his own inside joke, bringing an end to a magical night that should have happened a decade ago.

Hardaway walked the gauntlet of fans then, out of Springfield’s Symphony Hall, posing for final photos. As he got closer to me, I didn’t think about how I’d been lucky to be there his entire college career. Or how we were pretty close to the same age when I recruited him to the University of Texas at El Paso in 1985.

Instead, for some reason I thought 221-2340. That’s the phone number I’d called hundreds of times when Hardaway was a high school senior and I was a UTEP assistant coach. He shook my hand as he passed and quietly invited me to his after-party celebration. I went briefly, but it was too loud for me — and besides, I wasn’t in the mood for a party.

I was thinking about El Paso, Texas, and how perfect things turned out for him.

While this is Tim Hardaway’s tale, and how he finally got inducted into the Hall of Fame over the weekend of Sept. 9, it’s also a story about El Paso and its role in how America changed.

Hardaway’s off-handed comments on a radio talk show in 2007 badly delayed his once seemingly certain induction into the Hall of Fame. That’s the first of a couple conclusions that I’ve come to, although nobody ever really spelled it out.

Four years after retiring as a player, he said this on a Miami sports call-in show, “Well, you know I hate gay people, so I let it be known. I don’t like gay people and I don’t like to be around gay people. I am homophobic. I don’t like it. It shouldn’t be in the world or in the United States.”

His comments were in response to questions about the publication of former NBA player John Amaechi’s book “Man in the Middle,” where Amaechi revealed he is gay.

The NBA removed Hardaway from his scheduled guest appearance at the NBA All Star Game a few days later. He was ostracized in print and on television. This spring, however, 15 years later, the Hall of Fame announced that he had finally been chosen for induction.

Although Hardaway is pure Chicago, the long road to his induction — and the detour those comments took him on — begins and ends in El Paso.

His surprising sharp turn in 2007 put him squarely at odds with his own place in history. Today, it’s worth tracing his tracks to understand how things unfolded, the power of sports as an agent for social change — and the role of the city with the largest population center on an international border in the Western Hemisphere.

The city councilman

The story begins in 1926, the year a man named Bert Williams was born. Williams was raised by a struggling single mom in the Segundo Barrio, a virtually all-Hispanic area in South El Paso that sits right on the international line and has been called “The Ellis Island for Mexican immigrants.”

To this day it remains one of America’s poorest neighborhoods, although like all of El Paso, today it’s remarkably safe.

Before long, Bert Williams grew fluent in Spanish, although his childhood pals misunderstood him when he said his name — he was forever known in the barrio as Pájaro, Spanish for “Bird.”

Williams came home after serving in World War II and the invasion of Okinawa. He enrolled at Texas Western College (now UTEP), where he starred on their struggling basketball team.

Later, after law school, he returned again to El Paso and was elected to a spot on the five-person City Council. But he never was far from sports.

A world-class softball player, he convinced Texas Western’s African American baseball and basketball star Nolan Richardson to play as a ringer on his summer league softball team. Like Williams, Richardson grew up in Segundo Barrio, a fluent Spanish speaker.

This was in 1962, and El Paso, part of Texas and the old Confederacy, was still a Jim Crow town. Richardson, just 21, had been one of two African American players for first-year college coach Don Haskins the previous season. (Richardson was one of two Black players already on the team the day Don Haskins arrived to the border in his pickup truck, one of the many historical errors in the film “Glory Road.”)

One night, Richardson’s home run sparked a dramatic come-from-behind win for Williams’ softball team. It was a meaningless summer league game, but what happened after was profound. Williams insisted that he treat the young star to a meal at the Oasis restaurant.

Richardson knew what the story was there, even if a member of El Paso’s City Council did not. Sure enough, the waitress came over empty-handed. No water, no menus. “I can’t serve him in this restaurant,” she said, although she wouldn’t look at Richardson.

“I’ll be back,” Williams said.

Fueled by his own anger, the city councilman went home that evening to write El Paso’s anti-segregation law, the first of its kind in a city that was once part of the old Confederacy.

Both local newspapers, the El Paso Times and the Herald-Post, ran editorials condemning the proposal. The mayor vetoed the legislation, but Williams ignored that, and the death threats, and the onslaught of angry phone calls. He elbowed his way ahead by convincing his colleagues to override the veto unanimously.

The moment often is overlooked in the history of the civil rights movement. But El Paso changed well before the national Civil Rights Act of 1964, and before any other major city in the old South.

You can’t blame the media for the oversight. But you can blame the hero of the story, because Williams was exceedingly modest, not a self-promoter in any way. He handed out credit for the seismic change the way Tim Hardaway would hand out assists at UTEP three decades later.

In Williams’ telling, he was one of many, and his heroism was quickly forgotten, even in El Paso. Sixty years later, there’s only a bus depot named after him. He should have gotten a Cabinet position with President Lyndon B. Johnson, a statue, and one of the massive murals that El Paso is known for.

And, as you’ll see, Williams also should have been honored with a 1966 NCAA championship ring, but like an over-enthusiastic freshman point guard, I’m going too fast, getting out ahead of things.

The coach

Don Haskins, the new Texas Western coach, certainly noticed the end of Jim Crow in El Paso, though. And he made damn certain that an African American junior college kid named Jim “Bad News” Barnes noticed.

Haskins never had a Black teammate when he played at Oklahoma State in the early 1950s, but what did that matter? He had a soft spot for the downtrodden and the underdog. He also had the heart of a riverboat gambler. Although he refrained from making enemies needlessly, privately he had little regard for what the hell anyone else thought.

Haskins recognized that his junior guard, Richardson, was not only the best athlete in any sport on campus, but that he was among the best in the nation. And he sensed that the mostly Hispanic El Paso was a tolerant place, even before Williams’ groundbreaking legislation. It wasn’t the Mexican-American citizens who first set up El Paso’s Jim Crow laws, after all.

And with brown people at the heart of the college’s fan base, nobody on the border was going to complain about having too many players of color. (El Paso, like so many places, had its own complicated racial history. The Klan was a major influence in the 1920s, for instance, and it wasn’t easy for any person of color. But maybe it was a bit easier to be Black than in the rest of the South.)

Haskins had already been pursuing Bad News Barnes, his top recruit, intensely. The coach figured if Richardson had made himself into a local hero, other minority players might follow suit and push the Miner basketball team to national prominence.

But Barnes had had enough of both poverty and segregation. Anyone who can score 60 points in a high school game without shoes — in just his socks — as Barnes once did, instinctively senses he deserves a better life. Barnes made it clear to Haskins: he wouldn’t choose a college in a town where he couldn’t, for instance, sit wherever he wanted at a movie theater.

When Williams changed El Paso and ended its Jim Crow laws, Haskins suddenly had an advantage, and the coach ran with it by fully integrating his team. Barnes signed on, and he soon obliterated Texas Western’s scoring records, pouring in 29 points per game his final year.

The team finished 25-3. In 1964, he was the number one pick in the entire NBA draft.

The fact that the top college player in America flourished at an obscure school on the border got the attention of other Black athletes. Haskins now had a wide, convenient, and downhill entrance ramp onto Glory Road.

Texas Western shocked the world in 1966 — a year after Tim Hardaway was born — when it won the NCAA basketball championship with five Black starters. (In one of the worst-timed marketing moves ever, the school changed its name from Texas Western to UTEP the next year.)

Haskins remained an outlier, geographically and philosophically. Coaches in the 1960s still adhered to a quota on how many players of color a team or starting lineup might have, even after Haskins had shredded the unofficial rulebook. Soon after losing to Texas Western in the 1966 title game, for example, Kentucky signed one single African American player, their first ever.

Haskins rarely spoke of what had happened in 1966, partly because of the backlash and accusations that followed his historic win. Sports Illustrated attacked him, as did James Michener in his book “Sports in America,” for “exploiting” kids. But most rational observers and the UTEP players understood what the real criticism was: there was now going to be a flood of Black players all over America.

Haskins, like Williams, didn’t talk about his groundbreaking accomplishment, which was part of the reason that until 20 years after the historic 1966 title, his Texas Western team had never been honored with championship rings by the school. (Hardaway watched that ring ceremony from the sidelines as a UTEP freshman with his teammates.)

And El Paso remains isolated. And 80% Hispanic. Maybe that’s why it took Haskins so long to get inducted into the Hall of Fame himself. Lesser coaches like Lou Carnesecca and Marv Harshman (with three total NCAA tournament appearances, where he won two games) went in much sooner.

The only sign of the championship on the UTEP campus until the 1986 ring ceremony was the two-foot-tall standard-issue wooden plaque in the Student Union and a banner hanging in the Special Events Center. It wasn’t until the 2006 feature film “Glory Road,” which got so much incorrect, that UTEP realized the commercial appeal of the story. Soon after, they renamed the street the arena sat on “Glory Road,” and made serious moves to memorialize the team on campus.

While the 1966 NCAA title game wasn’t the “One Shining Moment” spectacle it is today, the game was nationally televised, and a generation of young Black men found inspiration in the El Paso college’s win. One wide-eyed viewer was named Bob Walters.

The mentor

Walters earned a fine reputation in the 1980s as a successful basketball coach at Chicago’s George Washington Carver High School. His best teams featured Tim Hardaway at point guard.

But back in 1950s Arkansas, where he grew up, Walters was a cult hero in the African American community. He was the state’s unofficial leader in career touchdowns in high school, including a staggering 32 touchdowns in 1959, his final season.

His totals, though, are “unofficial” — not because they weren’t keeping records, but because Walters, who ranked No. 3 in his class academically, played for a Negro “training school,” and therefore couldn’t compete against white teams. And back then, the University of Arkansas was a decade away from accepting its first Black football player.

Walters signed a scholarship at Northwestern University on the edge of Chicago, but he wound up starring instead at nearby North Central College, until a serious knee injury ended his playing days. He stayed in Chicago, though, and a couple years after graduating, he watched with rapt attention as Texas Western dismantled the all-white powerhouse Kentucky to win the 1966 championship.

Like most Americans, he’d never heard of Haskins until that evening in 1966. It must have been impossible for Walters to watch that game and not wonder what might have been different if he had been born a decade later.

But let’s not kid ourselves. Ending Jim Crow two years before Congress acted is commendable, but hardly cause for celebration. El Pasoan Thelma White sued when she was denied admission to Texas Western College in 1955, a full year after the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision. That eventually opened the doors for Black students in Texas, but by then White had already enrolled up the road at New Mexico State.

And Haskins wasn’t in charge of hiring at the university — at the time of the epic win in 1966, Texas Western still had never hired an African American professor. In the 50-something years since then, UTEP has hired 12 head football coaches. None of those coaches have won a bowl game. And none have been African American.

In any case, it would have been a different story — a different history — if Williams and El Paso hadn’t ended the city’s Jim Crow laws and opened the door for Haskins to recruit any player regardless of skin tone. And it would have been different if Haskins’ school had not been set in a mostly Hispanic city that was far more progressive than the rest of the South.

What if Haskins had instead been coaching in a stronghold of the old Confederacy in the 1960s?

The protege

That’s where Nolan Richardson found himself when he landed in 1985 at the University of Arkansas as the Razorbacks’ head coach. He had plenty of emotional scars due to the tribulations in dealing with racism, and those never left him. (One of many examples was that before Haskins arrived, the prior Texas Western coach had left him behind because the Shreveport tournament the Miners were scheduled to play in had a “no Negroes” rule.)

Richardson was hired at Arkansas by Frank Broyles, the powerful athletics director who had coached great all-white football teams there in the 1960s. Broyles was also the football coach who had declined to recruit Bob Walters in 1959. (No black football player would take the field for his Arkansas football teams until Jon Richardson — no relation to Nolan — in 1970. Ten other colleges in Arkansas desegregated before the big state university.)

Richardson had begun his coaching career when there was not a single Black head coach in major college basketball — his only model was Don Haskins. But he’d heard of two overlooked African American coaches from smaller schools who would become practically gods to aspiring minority coaches: John McLendon and Clarence “Big House” Gaines.

Still, Richardson gleaned what he could, and he came up through the coaching ranks the hard way — first a decade of high school success in El Paso, then on to junior college, where his NJCAA championship vaulted him to Tulsa University and then Arkansas.

Richardson was sometimes viewed as a troublemaker because he caused a ruckus wherever he saw injustice. He called out schools in their hiring practices, stood up for Black kids on his campus, and rejected the subtly racist coding by TV analysts: He was often tagged as a “great recruiter,” which ignored his Star Wars-paced wrench-in-the-lawnmower “40 minutes of hell” strategy that influenced countless coaches.

Richardson never lost his edge, or his anger at being overlooked. “He seems to make a system out of anger,” Alexander Wolff wrote in Sports Illustrated. Even after he won the NCAA title in 1994, Richardson never kept quiet about racism or injustice. This was perplexing to the media — how can a man making a million dollars a year call the system racist?

But Richardson wasn’t usually talking about himself. Rather, it was the plight of all Black coaches that irked him.

When he was dumped by Arkansas after going ballistic at a press conference in 2002, virtually every major media source said it was his own fault. (Richardson railed about slave ships and double standards, and even seemed to dare the university to fire him. “If they go ahead and pay me my money they can take my job tomorrow” was one quote. The few people who knew his history understood his outburst. Nobody else did.)

Later, Richardson stumbled in the WNBA, but he had an impressive-but-brief run as the Mexican national coach, where his fluency in Spanish and charismatic style quickly endeared him to the players. Richardson kept his rustic ranch on the edge of Fayetteville where he lives to this day.

History has proven Richardson — like Bert Williams and Don Haskins — right about nearly everything. Strictly from a basketball-is-a-business sense, in the decade after Richardson was fired, Arkansas would win a single NCAA tournament game. And Richardson seems to have been a man out of time — he was dismissed for pointing out decades ago what America has finally gotten around to debating today.

Tim Hardaway chooses El Paso

It’s not a straight line from Bert Williams to Nolan Richardson to Don Haskins to Bob Walters to Tim Hardaway. The dots connect more like an asymmetrical web, but they’re indeed interconnected.

All of Hardaway’s basketball forefathers listed above were supporters of the subjugated, their stances honest and uncontrived. Hardaway was from a different generation, and he’s the only one who actually starred on the court at the professional level.

Before he accidentally became part of the sport-for-social change tradition that sprouted in El Paso, Hardaway was just the latest in another tradition of Chicago point guards: Rickey Green and Quinn Buckner. Maurice Cheeks and Kevin Porter. Isiah Thomas and Doc Rivers. Even the ones who weren’t NBA All Stars, or league assist leaders or All Defensive team picks — like Randy Brown and Jim Les — were known for being unselfish, tough, and team-first.

This is the part where I stumble into the story, a Division III benchwarmer from Chicago, and, at age 24, an unlikely major college coaching candidate.

In 1983, I was accepted a graduate assistantship on the UTEP staff, where my duties were mostly to help one of the other assistant coaches, Tim Floyd, with recruiting. My first year, Floyd came back from a tournament with a name scrawled on the edge of an envelope: Tim Hardaway. Floyd had not seen him play, but he had been tipped off that the kid might be worth checking out.

I was already making some calls to Chicago that spring when Don Haskins promoted me and I had to trade my graduate assistantship for a yearly salary of $10,000. The first thing I did that September of 1984 was, like a homing pigeon, fly to Chicago to check out Hardaway. I learned that his father loomed large — even after he started to shine at UTEP, he was still known as “Donald Hardaway’s son” on Chicago’s south side.

Donald Hardaway Sr. was a local playground basketball star, although he hadn’t played college ball. Stories of fathers teaching their sons to swim by tossing them into the deep end are legion, and Donald did something similar. From the time Tim could walk, Donald would bring his dribbling-obsessed son with to get him to pickup games.

Before he was a teen, he was getting chosen to play. “I rarely played with kids my age unless it was at school,” Hardaway recalls. “I was playing with the men in the neighborhood.” That’s where he received his old-school education. Team play, unselfishness, passing, and ball-handling were the subject matter at hand. And winning. Little else mattered.

At our initial meeting at his home in South Shore, Hardaway carried himself with humility. Even his nickname then — “Tim Bug” — seemed pretty modest. Yet, just as I was leaving, the last thing he said veered wildly away into the stratosphere. “Some people say I play like Isiah Thomas,” Hardaway said with a straight face.

I didn’t know how to respond, as Thomas was then the best small player in the world. And at this point, in an odd cart-before-the-horse situation, I still hadn’t seen Hardaway play. It was September, so pickup ball the next day was the only option.

“Watch for how hard he plays,” head coach Don Haskins had reminded me before I left El Paso.

If I’d used Haskins’ crucial evaluation test, I’d have walked away in the middle of the three-on-three game at South Shore Park. Hardaway stood straight up when he didn’t have the ball, and he hardly broke a sweat. But he had the most underrated ability a player can have: perfect balance. Most importantly, he possessed a sort of oracular imagination for plays developing, a vision that video game designers can only dream of.

That vision, according to his elementary school coach and longtime friend Don Pittman, is what set Hardaway apart even by the sixth grade. “He could create something out of nothing,” Pittman told me at the induction ceremony.

Just to be certain I hadn’t been hallucinating at the outdoor park, I watched Hardaway a few days later playing at the South Shore YMCA. That’s where a young star named Ben Wilson told me, “Whoever signs Tim Hardaway will be very, very lucky.”

In November of 1984, when the early signing date rolled around, Hardaway had a choice: he could sign at UTEP, where a 24-year-old assistant had been calling him virtually every evening. Or he could take his chances at Western Illinois University, a school that still has never earned a bid to the NCAA Division I tournament.

Easy decision, right?

But there was a third choice.

And that choice was one that most high school coaches might have advised their star players to choose: wait. Wait for April’s signing date when there’d surely be more choices. It made little sense to sign in November when only two schools offered full rides.

But Bob Walters was among a sort of lost generation of athletes whose own careers were curtailed by Jim Crow. He understood both Haskins’ impact on college sports and history. And while Walters is the only person in this story who never lived in El Paso, he must have wanted his protégé to be part of that history.

Nobody in Chicago knew Walters’ story, the staggering 32 touchdowns as a high school senior, the top-flight grades, his being ignored by major schools in the south. Coach Haskins didn’t know, nor did I. Because Walters, like Bert Williams and Don Haskins, didn’t talk about himself.

Walters never told me exactly why Hardaway signed early, and like anyone who gets lucky, I assumed I deserved the good fortune, and all the accolades that his El Paso stardom meant for my reputation. For years I accepted the praise for my “eye” in uncovering Hardaway.

Walters died of cancer at age 43, at the start of Hardaway’s sophomore season, and true to form, the coach hadn’t told anyone of his struggles. Even if I’d begun to question my own good fortune associated with Hardaway’s joining UTEP — I hadn’t, not yet — it wouldn’t have been the kind of thing I could have pressed Walters about, and when I spoke to him by phone the day before he passed away, it was too late.

Even if I had asked him, I doubt Walters would have said, “I was still struggling to come to terms with American history and the civil rights movement and my own past disappointments, and Tim going to play for Don Haskins would be poetic justice and provide me with a sense of peace.” But that’s the only explanation that makes sense. And while nobody has ever suggested that to me, I believe it to be true.

“Mister Walters never told me that,” Hardaway said. “Looking back, he wanted me out of Chicago, to get away and experience another culture and grow up as a man. And he knew that it was best to get away from friends, even family, and any outside influence.”

Walters did, however, detail for his young star what it was like growing up in the Jim Crow South. He also shared his experiences playing football briefly at Northwestern, where a coach told Walters he wasn’t to be talking to white college girls. They were off limits.

“He thought it was going to be different in the North,” Hardaway says, “and he learned that Chicago could be just like the South.”

Still, nearly 30 years later, I’ve come to believe that I’m correct about why Walters wanted Hardaway to sign early at UTEP — even if Hardaway sees it another way. You can decide for yourself.

A star player emerges

Hardaway returned from Walters’ funeral determined to keep improving. He already knew when to stomp on the gas pedal, and he sensed when to put on the brakes. Under Haskins, he also learned when to penetrate, how to set up a half-court offense, as well as the subtleties of team defense.

Hardaway also had a rare grasp about what not to do: over-dribble, keep the ball too long on fast breaks, or toss up ill-advised shots. Most importantly for any UTEP player, he also learned when to tune out Haskins and ignore him — or, more precisely, to not take criticism personally. Unforced mistakes were a sin. So was talking back or saying anything disrespectful.

Everyone believed Hardaway couldn’t shoot, and they were mostly correct — initially. He sank just three 3-point shots as a sophomore, the first year the new line was in effect. But he gradually got up to 35.2% as a senior, a respectable number, sinking a total of 48 that year. (Through sheer repetition, he was able to continue his improvement despite his shot having no backspin. In the NBA, with the three-point line considerably deeper and the defenders far bigger and more intense, he still made 35.5% of his long-distance attempts over his career. To put that in perspective, Larry Bird — who won a trio of NBA 3-point contests–made 37.6%.)

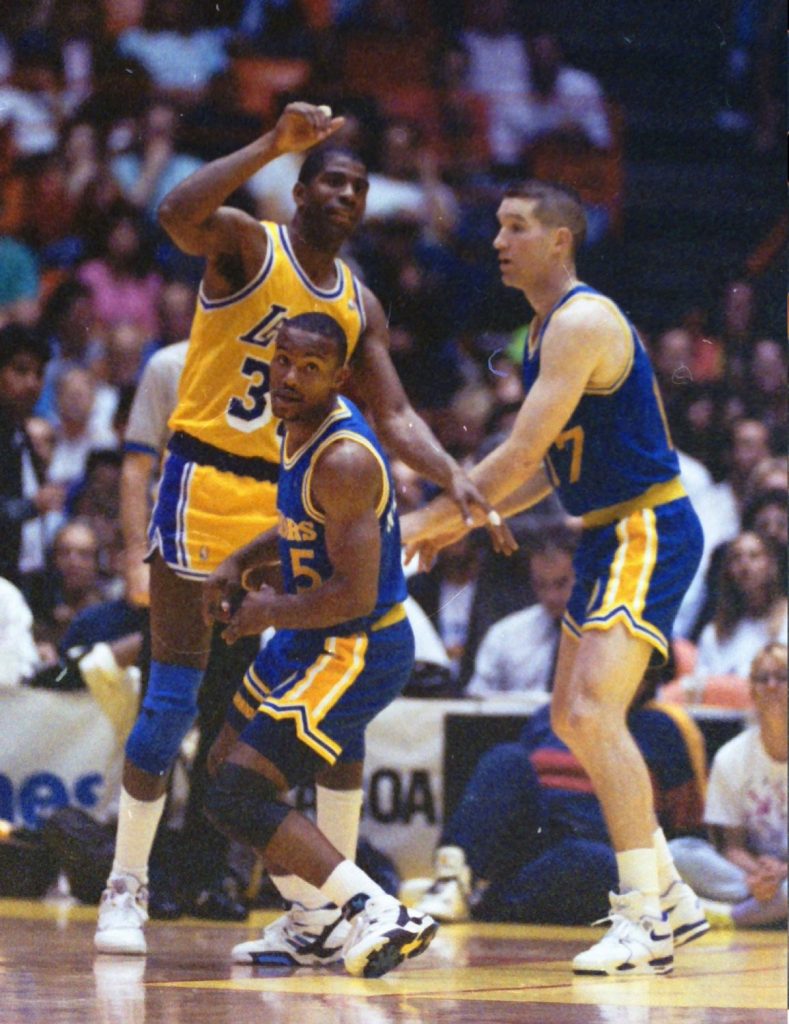

And Hardaway kept polishing his signature move, the crossover dribble that would paralyze defenders and became known as the “UTEP two-step.”

Haskins was noted nearly as much for his longevity — 38 years at one single school — as for his win total (719) or his historic barrier-breaking 1966 team. Hardaway had a similar mindset — he never dreamed of switching high schools, even when Don Pittman, his talented grade school coach who assisted Bob Walters briefly, left Carver High School for a head coaching job.

When Hardaway’s backcourt mate at UTEP, Jeep Jackson, died in 1987, he stayed put in El Paso. His first-and-only NBA agent, Henry Thomas, was a longtime family friend. Hardaway even married his high school sweetheart, Lady. They’re still together.

“I’m loyal,” Hardaway says. “Loyal to the people that have been loyal to me. If you steer me wrong I don’t mess with you.”

“I’ve always said about Tim,” Pittman says, “he’s intensely loyal, and he listened to people he felt were supportive of him.”

Hardaway adds, “I know how to weed people out.” He says that filter comes from growing up on Chicago’s south side. “On the streets, you have to know who to trust and you have to figure that out quickly and make a decision.” That instinctive quick decision making became another of his tools on the court.

Like an Old Testament prophet, Hardaway begot other UTEP stars from Chicago: Marlon Maxey, Johnny Melvin, Ralph Davis, Antoine Gillespie. None were quite as great as Hardaway, but they were damn good, good enough to secure successive NCAA bids for UTEP and carry the Miners to the Sweet 16 in 1992. In essence, the Chicago kids who followed Hardaway comprised the second-best team in UTEP history.

My reputation spread as some sort of guru of the Windy City high school scene, and as a shrewd judge of talent — I’d “discovered” Tim Hardaway in a stroke of genius, and I sometimes even got credit for teaching him his breathtaking dribbling skills. Some UTEP fans acted as though I’d invented him. Almost none of it was true.

Nobody should quickly summarize Hardaway’s accomplishments after UTEP and in the NBA, but I’m going to do it here:

He was named College Player of the Year Under 6’0”. He was MVP of the Western Athletic Conference and UTEP’s career scoring leader when he finished. He was chosen in the NBA drafts’ first round and was an NBA All Star selection five times. He won an Olympic gold medal in 2000. He’s one of only seven players to average 20 points and 10 assists in a single season. He was named All NBA First Team in 1998, when he finished fourth in the MVP voting — the experts deemed only three players in the league were better than Tim Hardaway.

Hardaway’s success — and his astonishing ball-handling skills and just-plain-fun Nike commercials — made Hardaway into a cultural icon. Kids all over the world have tried to imitate his killer crossover. And the simple truth is that fans gravitate toward smaller players. Nearly everybody sympathizes with the underdog; nobody cheers for Goliath. Little guys even get more lucrative shoe contracts. Few players were as popular as Hardaway.

Besides, Chicago point guards are emblematic of guts, fearlessness, courage. They’re also the epitome of unselfishness and generosity–that’s what an “assist” indicates, a generous sharing. (When a former player named Shawn Harrington saved his daughter’s life in a mistaken-identity shooting in Chicago in 2014 — but paid the price and was paralyzed for his heroics –there was plenty of talk about it being the ultimate unselfish point guard decision.)

A hateful comment

Maybe that’s why we were all so stunned when Hardaway said what he did on the radio about gay people. He’d never done or said a mean thing in his adult life. Sure, he had shown plenty of mental and physical toughness over the years, but that was on the court. And it never veered toward cruelty. Unless you thought that breaking defenders’ ankles with the UTEP two-step was cruelty.

Can you imagine the courage it would have taken for John Amaechi to admit he was gay at that time? Tim Hardaway, at the time, apparently could not.

As Hardaway’s comments proliferated across the internet, there were discussions in the basketball community that he was merely saying aloud what many players still thought. Maybe, the thinking went, this would lead to open discussions, communication — and change.

Change. The world of sport has long been the leader in America for profound social change. Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers 1947 — two years before the U.S. military desegregated. Muhammad Ali’s “I got no quarrel with them Viet Cong” stance was just as dramatic. And David Meggyesy, at the height of his NFL career, quit to join the anti-war movement.

Bill Russell, Billie Jean King, Jim Brown — all were politically outspoken and active. There were, of course, pioneering coaches like Don Haskins and Nolan Richardson, both Hall of Famers themselves now.

The most lasting image of 1960s sports might be John Carlos and Tommie Smith at the 1968 Olympics with their raised gloved fists. They paid dearly for their political stances.

And so did Hardaway, who was instantly a persona non grata after 2007. He was floating in the abyss — among the smartest players ever to play, with a wealth of knowledge to share, but nowhere to share it, except with his NBA-bound son, Tim Hardaway Jr.

In the immediate aftermath of the radio show fallout, rather than hosting a press conference to undercut, deny, spin, and save face, Hardaway stepped back, allowed things to develop slowly, and read the situation — the way he’d always done on the court.

He attended all-day seminars at Miami’s YES Institute, which offers support for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender teenagers. He learned about the struggles gay teens had dealing with their own parents, their high suicide rates. He discovered that more than a few of his closest friends had sons and daughters who identified as gay. And the two women he saw at lunch every week that he counted as friends? And his goddaughter? And that childhood pal from elementary school? Gay.

In the meantime, three of his Golden State Warrior teammates with similar — but not greater — resumes got selected for the Hall of Fame. But no Hardaway. Those sports radio comments were like a screen set by Shaquille O’Neal: impossible to get past.

The irony of the situation was obvious. Consider the astronomical odds against a Black kid from the South Side of Chicago even being a college player. And what about the chances of a 5–foot-11 guy making the NBA? His life was a million-to-one shot. What must that have felt like for Hardaway?

I certainly felt it. The one time I talked to him about his NBA chances, back in 1988, I told him, “Maybe you’d better have something to fall back on in case the league doesn’t work out for you.”

Hardaway didn’t like that suggestion — I’m sure he thought I was doubting his ability — but I believed I was doing him a favor. I meant that it would be worth it for him to finish his degree. While few people were closer to his situation than I was, I couldn’t have guessed he’d be a Hall of Fame player whose crossover dribble and astonishing skills would have a huge impact on basketball culture all over the world.

Things changed slowly and organically for Hardaway, and it happened in perhaps the least glamorous and most isolated city in America: El Paso, Texas.

El Paso and the path to redemption

In 2011, four years after his radio comments, Hardaway was back to the border for a golf outing when he learned of the controversy brewing. City Council members Susie Byrd, Steve Ortega and Beto O’Rourke had pushed through equal employment benefit rights for all domestic partners of El Paso city employees — even gay partners.

A pastor-led backlash followed and voters overturned the policy in a 2010 election. The City Council voted to reinstate domestic partner benefits, and opponents then began circulating petitions to recall Byrd, Ortega and Mayor John Cook. (O’Rourke had left the City Council by then.)

The recall effort, by chance, was underway just as Hardaway would be back in town for a golf benefit outing. When Hardaway got wind of the situation, he had a long meeting with Byrd, then offered to explain to El Paso voters his own change of heart. There might have been 20 people at the outdoor press conference — nothing like the overflow crowds and media blitz for his Hall of Fame induction last week.

But it felt authentic, genuine, fresh — not a spin or denial or damage control operation at all. Hardaway spoke from the heart. “It’s not right to not let lesbian and gays have equal rights here,” he began. “Just like El Paso came together in 1966 when Don Haskins started those five guys, I know this city will grow and understand that gays and lesbians need equal rights.”

It should have been a national story, just as Bert Williams ending Jim Crow should have been 50 years earlier.

But that wasn’t Hardaway’s point, not his aim. “We shouldn’t ridicule and bash them,” he went on, “but understand what they stand for and what they’re doing.” He encouraged everyone to support the endangered City Council members. Near the end of the event, he said, “I wanted to put my opinion out there, and try to help El Pasoans grow up and catch up with the times and understand this is the right thing to do, to give gay and lesbian partners equal rights and go forward.”

Courts eventually ruled the recall efforts were improper. El Paso voters in 2013 narrowly approved placing domestic partner benefits in the City Charter, basically the constitution for the municipal government.

The practical influence of Tim Hardaway — the most popular sports figure in a city of 800,000 with no pro team — admitting he was wrong is impossible to measure. Exactly how many people changed their minds because Hardaway did? Who knows.

While El Paso was behind other progressive cities on the issue, for a town with a Catholic majority to make that move was profound. El Paso, of course, means, “The Pass” — a place where people cross over. That seems fitting for Hardaway, the crossover king, whose legit and honest change of heart was another kind of crossing.

A Hall of Famer

Like anyone honored for their life’s work, Tim Hardaway was in a pensive mood in the days after the Hall of Fame induction. He talked about his parents, his grandmother, his kid brother, Donald Jr.

“It all began with people teaching me right and wrong, what you need to do, and just as important, who not to follow. And I was lucky because I had great coaches.” He names them constantly: Don Pittman in elementary school, Bob Walters, Don Haskins, then two of the NBA’s best, Pat Riley and Don Nelson.

Hardaway was the first person to speak at the 2022 Hall of Fame ceremony, and that was fitting: he’d been waiting the longest and should have been inducted a decade ago. He was entitled to go first. And in most ways he had already bounced back, even before his induction. After serving as a Detroit Pistons assistant coach for a few years, he recently signed on with the New York Knicks as a scout. He’s moved on.

I can’t seem to move on, though. I still think about Bert Williams and Nolan Richardson trying to order hamburgers that night at the Oasis in 1962. What if Richardson hadn’t opted to go along for the meal? And how could Don Haskins not have known the implications of what he was doing versus Kentucky in 1966? And why didn’t he get Williams an honorary championship ring 20 years later when the team finally did? Why didn’t Bob Walters convince Hardaway to wait until the spring to sign, when bigger schools would have been flocking to Carver High School? And how did Hardaway glean the wisdom to wait for just the right time — and place — to publicly stand up for gay people?

“Everyone has a path,” Hardaway says, “and I did too.”

Still, I wonder. I’ll probably never be certain. But I know this: Hardaway’s evolution was another move in a long line of important ones made by somebody with ties to El Paso, Texas — a gutsy reckoning that brought him squarely back to the rightful historical place he’s inherited.

Not just the Hall of Fame, it’s far bigger than that: Hardaway used sports as a platform to make El Paso better, and to change the world. His rightful place is with Bert Williams, Nolan Richardson, Don Haskins and Bob Walters. That’s quite a starting five.

This article first appeared Sept. 25, 2022 on El Paso Matters and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Rus Bradburd is the author of four books, including “Forty Minutes of Hell: the Extraordinary Life of Nolan Richardson.” He worked as a college coach for 14 seasons, and his eight years at UTEP helped the team to seven NCAA tournament bids.

Along with former UTEP player Steve Yellen, he has directed “Basketball in the Barrio” for 30 years. He lives in Las Cruces and Chicago. Learn more at rusbradburd.com.