As in-person classes in El Paso schools resumed after the height of the pandemic, child protection workers say they saw a spike in abuse reports and the need for safe foster homes for children removed from dangerous situations.

“One of the number one reporters of abuse and neglect are the teachers,” said Oscar Millán, foster care program director at El Paso Children’s Center.

When schools conducted classes online, red flags teachers see with students – like bruising, students staying late or even staying home from school – were harder to observe and evaluate virtually, and abuse reports fell.

Now that students have returned to school, things have changed.

“When everybody went back to somewhat of the new normal, a lot of the teachers that were seeing the kids, now face to face, they’re seeing what’s going on. So, there was, again, a huge need for foster parents,” Millán said.

In 2021, the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) reported that 176 children were placed into foster care in the El Paso region, a 4% increase from 2020.

In the first five months of 2022, the El Paso region had 126 children in foster care placements, according to DFPS data.

Yet, last year only 34 foster homes were screened and approved through DFPS in the El Paso Region, which includes Brewster, Jeff Davis, Culberson, Presidio, Hudspeth and El Paso counties. That’s just two more foster homes than were approved in 2020.

Foster parents in Texas must meet certain requirements before having a child placed in their care. This includes completing an application, undergoing background checks, attending training sessions and agreeing to a home study where a caseworker inspects the home and conducts interviews with the potential foster parents.

Agencies like El Paso Children’s Center conduct orientations for new families interested in fostering, but Millán said the interest hasn’t been strong.

“When we have our orientations, the last Tuesday of the month, it’s kind of like, sometimes we get five people, sometimes we get three people, sometimes we get no one. So it’s pretty alarming,” he said.

Child-advocacy organizations like the non-profit El Paso Children’s Center don’t have the budget to do marketing beyond their social media accounts or website, Millán said. So they rely on word-of-mouth to find willing parents to foster.

In Texas, the state’s first goal for children in foster care is reunification with their biological families. If caseworkers determine that is not a safe option, the state may move to terminate parental rights in court.

Texas offers a foster-to-adopt program where foster parents may choose to become adoptive parents if kinship placement is not an option. A foster family becoming an adoptive family is considered less disruptive to a child’s life as they establish a relationship with their adoptive family throughout the process.

While fostering, parents are reimbursed many of the costs of taking care of a child such as buying clothing, food, transportation and more. According to the DFPS, the basic rate is $27.07 a day, though it may be higher if a child has higher needs.

Choosing to foster-adopt

Vanessa, a foster mother who asked to go by her first name to remain anonymous as she nears the end of the process of adopting her foster children, made the decision to become a foster family after six years of failed fertility treatments.

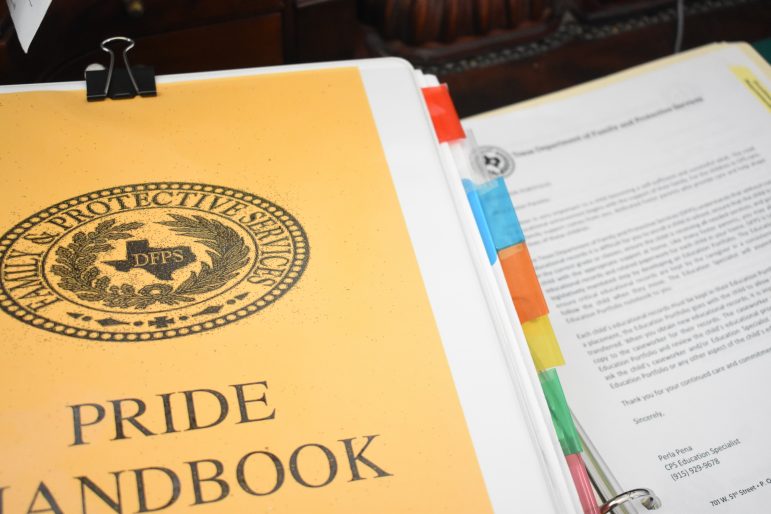

To meet the qualifications for fostering, Vanessa and her husband had to attend months of training with the Child Protective Services PRIDE program. That included watching videos about domestic abuse, neglect, violence, and drug abuse which at times, she said, was hard to sit through.

“It’s pretty — let me put it this way, it’s bad. But (fostering children), it’s a good way that you can help a child,” Vanessa said.

Vanessa said she and her husband had been looking to take care of children between the ages of 0 to 5, but after learning more about the circumstances children might have experienced before foster care, they were “open to anything.” The pair ended up with a placement of three children, all under a year old.

“They brought so much joy to my heart and to me and my husband,” Vanessa said.

Unfortunately, there are still many more children waiting for foster families, said Paul Zimmerman, a spokesperson with the Texas DFPS.

Even once a family has qualified to foster, Zimmerman said, there are a variety of reasons they may drop out of the program. Some may stop fostering after experiencing burnout. Others may stop fostering after adopting a child.

“We’re always looking for more foster homes than we need and we need them for all levels of care,” Zimmerman said.

While most applicant homes meet the basic level of care, finding placements to match higher levels of care is a challenge. This may require extra training to provide for children with developmental or mental health issues.

Vanessa started to take her foster children to counseling after the children began to experience extreme emotional distress everytime she left them at the facility for parent visits.

“How they cry, it will literally break your heart. It’s like traumatizing that child that you’re leaving there.” Vanessa said.

Children in foster care are eligible for Medicaid and therapy or any other medical needs are covered by the child’s insurance. But, sometimes children may need more intensive care and ultimately be placed in a facility out of town because El Paso doesn’t have a residential treatment center, Zimmerman said.

In Texas, the RTC program exists for DFPS to provide children intensive mental health care at an RTC while their guardian keeps legal custody of the child. The program covers the cost of an RTC for families who may not have the resources to pay for the placement.

While El Paso has treatment centers treating those with drug addiction and behavioral health issues, the nearest residential treatment center is as far as nine hours away in San Marcos, Texas.

Millán of El Paso Children’s Center said the center offers training locally to help foster parents understand the needs of children who have experienced trauma.

The training is called Trust Based Relational Intervention and done in four days, with refresher sessions after because understanding trauma is not done quickly, Millán said.

“We always use the example of the iceberg. You know, you see the tip of the iceberg but there’s a whole lot going on underneath,” he said.

To learn more about being a foster parent in El Paso, the El Paso Children’s Center holds informational orientations the last Tuesday of every month at 11 am and 6 pm. To RSVP contact (915) 259-6382 or foster@epccinc.org