In 1901, a cook named Wong Kim Ark crossed from Juárez to El Paso with a unique distinction. He was perhaps the only person in the world who had a U.S. Supreme Court ruling declaring him by name to be a citizen of the United States.

That didn’t prevent an El Paso immigration official from arresting him and beginning deportation proceedings.

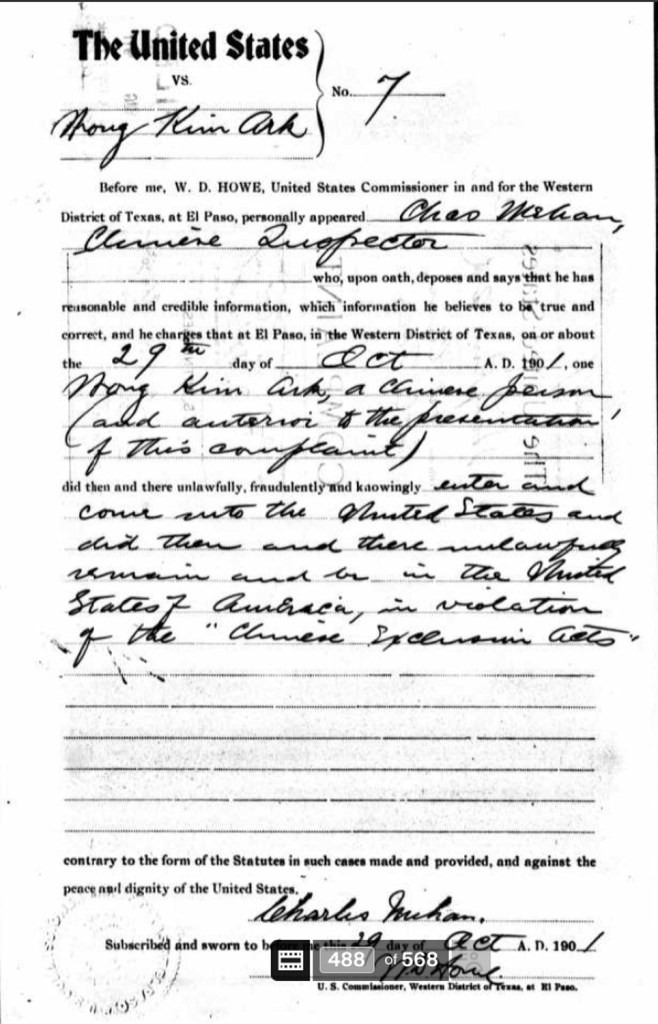

On Oct. 29, 1901, Charles Mehan, a “Chinese inspector” in El Paso, arrested Wong on the grounds that he was in the United States in violation of an 1882 law called the Chinese Exclusion Act.

It took four months for Wong to win a ruling – again – that he was a U.S. citizen and couldn’t be deported. That verdict in El Paso came almost four years after the U.S. Supreme Court, in a landmark case, had settled the issue of citizenship for Wong and other children born to immigrants in the United States.

Wong’s landmark legal case is well known among legal scholars, but his run-in with El Paso immigration authorities after the Supreme Court ruling was lost to history until scholar Amanda Frost discovered the records in the National Archives and wrote about it in 2021.

Frost, a law professor at American University in Washington, D.C., said the immigration enforcement system that targeted Wong more than 120 years ago was a precursor to what the United States has today.

“The Chinese Exclusion Act created a bureaucracy that then needed to justify itself, and that grew exponentially. Once the government started excluding people, it needed to decide who was eligible. That meant it needed to interview witnesses, review documents, etc. That required translators, officials, commissioners, etc. And in turn it required building detention facilities to hold all the immigrants waiting to enter,” she said.

“All that bureaucracy generated more paperwork, more scrutiny of immigrants, and the need for more and more officials and more government funds to pay for it all.”

In El Paso, Wong would be a target of that policy.

A historic case

The 1898 Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Wong Kim Ark established that the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted “birthright citizenship” to most people who were born in the United States. As president, Donald Trump occasionally threatened to revoke birthright citizenship, but legal scholars said the Wong ruling prevented that.

The 14th Amendment was passed after the Civil War in 1868 to clarify that the country’s formerly enslaved people were citizens and had legal protections. It said: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first significant federal law restricting immigration into the United States. The law, which remained largely in effect until 1943, barred most Chinese people from coming to the United States, and prohibited them from becoming naturalized citizens.

“The Chinese Exclusion Act was really the birth of our modern-day immigration system,” said Frost, the author of a 2021 book, “You Are Not American: Citizenship Stripping from Dred Scott to the Dreamers.”

Wong Kim Ark was born in San Francisco around 1870 to parents who had emigrated from China. Like many children of immigrants, he maintained contact with his ancestral land while trying to make a life in the United States, a country that was often hostile to his existence. During his working life, he sent part of his earnings back to relatives in China.

Wong traveled several times to China during his life. Biographers have found that his parents took him back to China when he was about 8, and they never returned. He came back to the United States with an uncle around age 11 and immediately went to work as a cook in California.

U.S. laws and customs forbid Wong from marrying women not of Chinese descent. He returned to his parents’ village of Ong Sing in 1889 and married a woman named Yee Shee and they conceived their first child. He returned to San Francisco in July 1890, leaving his family behind in China.

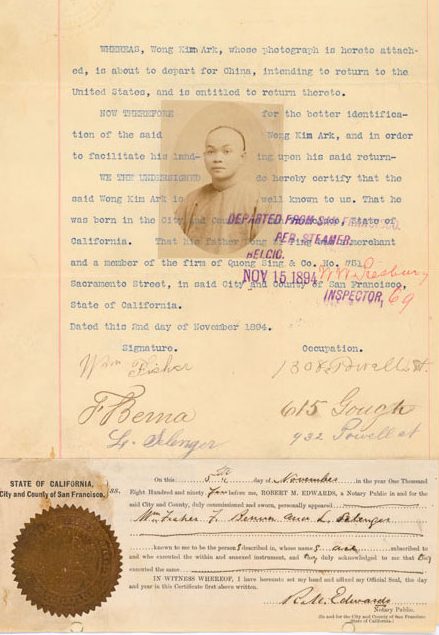

Wong also returned to San Francisco from a nine-month trip to China in August 1895, again leaving his family behind. Although he had been allowed to return to the United States twice previously, this time he was detained by U.S. immigration agents looking for a court test of whether the 14th Amendment granted birthright citizenship.

The case made its way to the Supreme Court, which ruled 6-2 in March 1898 that Wong and other children born to immigrant parents in the United States were citizens. It is one of the most impactful Supreme Court opinions in history.

Wong Kim Ark in El Paso

In October 1901, three years after having his citizenship confirmed by the Supreme Court, Wong Kim Ark came to the El Paso border through Juárez. It’s not clear why he went to Mexico, but both sides of the border relied on Chinese labor and merchants as former frontier communities grew rapidly after the arrival of railroads in the late 19th century.

The 1900 census listed 336 people of Chinese descent among El Paso’s population of 24,886. Almost all were men, mostly in service occupations such as laundry and restaurant work, though some were listed as physicians. Most of the people of Chinese descent in the 1900 census in El Paso listed their date of arrival in the United States before the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.

El Paso had begun to boom after the arrival of railroads in 1881, when the city had about 2,000 residents. Frost said Chinese laborers performed jobs such as cooking and laundry that were traditionally done by women, who were often rare in frontier towns.

Northern Mexico also had a sizable Chinese immigrant population at the turn of the 20th century. Wong’s plans to cross from Juárez to El Paso – and his role in a historic Supreme Court case – were noted by the El Paso Times on Oct. 29, 1901.

“Wong Kim Ark, the Celestial who the United States supreme court decreed was a citizen of the United States and not a subject of the Boxer land, and who has been temporarily residing in Juárez awaiting an opportunity to enter the country again legally, will doubtless have his case adjusted in a few days,” the paper said in a story on Page 3. (The Celestial Empire and Boxers were terms used by American media to refer to China and its people in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.)

Wong was initially rejected in his efforts to return from Mexico, the Times report said. “Evidence has arrived, however, to show that the Celestial in Juárez and Wong Kim Ark whose citizenship was passed upon in (1898) are one and the same. In that event, and the federal decision being still in force, his admittance will be beyond question.”

The same day the Times story was published, Wong was arrested by Charles Mehan, the man responsible for enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Act in El Paso.

Winning his freedom – again

The Times story indicates that Wong’s status as a U.S. citizen was known in El Paso at the time of his arrest by Mehan. But the charging document doesn’t mention the Supreme Court case, and refers to Wong as “a Chinese person.”

Many people arrested by Chinese inspectors were locked up until being deported. Records in the National Archive show that Wong was freed on a $300 bond – the equivalent of more than $10,000 today.

The bond was guaranteed by Mar Chew, who is listed as a restaurant owner in city directories, and R.F. Campbell, El Paso’s mayor from 1895-97 who was then serving as the city’s postmaster, a powerful political position, records show. The connection of the two men to Wong isn’t stated in the records maintained in the National Archives.

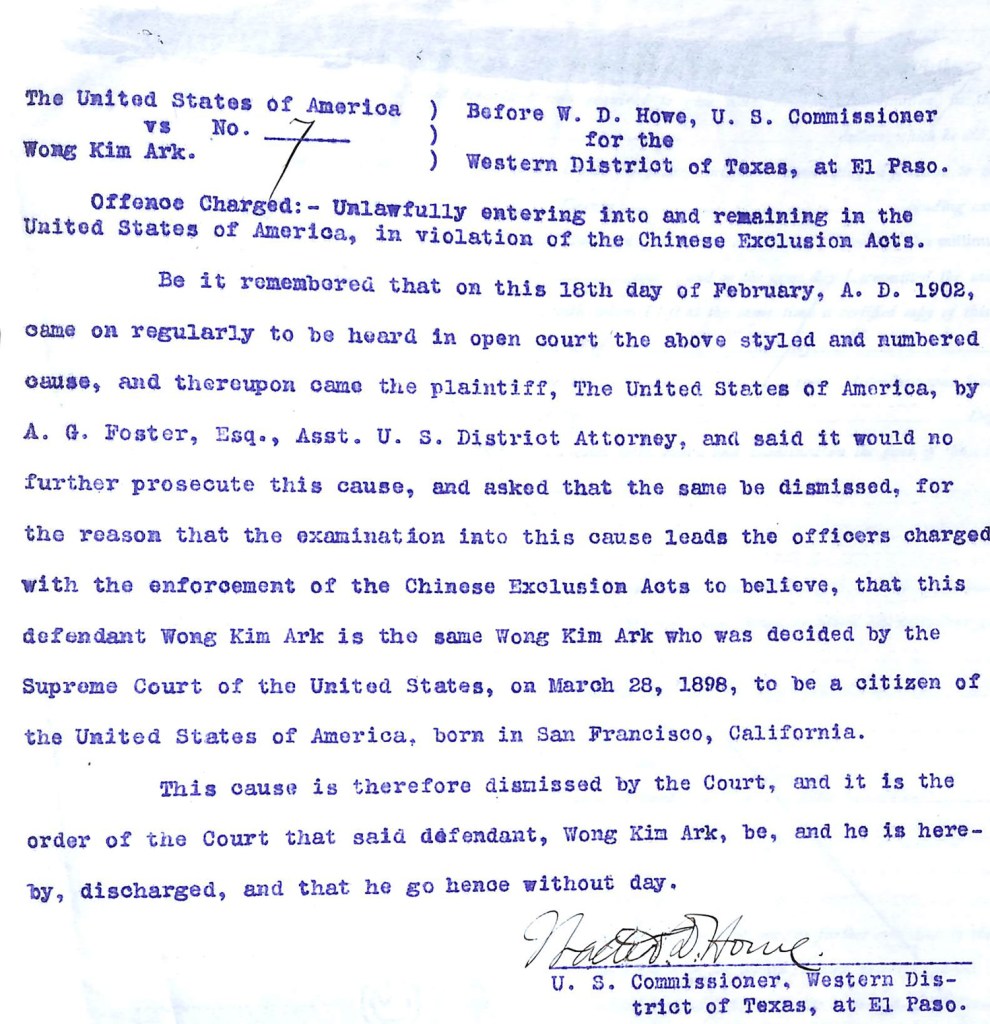

On Feb. 18, 1902, Wong’s potential deportation was dismissed by W.D. Howe, a federal commissioner for the Western District of Texas, at the request of federal prosecutors.

Howe wrote that “examination into this cause leads the officers charged with the enforcement of the Chinese Exclusion Acts to believe that this defendant Wong Kim Ark is the same Wong Kim Ark who was decided by the Supreme Court of the United States, on March 28, 1898, to be a citizen of the United States of America, born in San Francisco, California.”

Life after El Paso

It’s unknown how long Wong stayed in El Paso. A person named Wong Kim Ark is listed in a 1903 city directory living in a boarding house at 225 S. Oregon St. His occupation is given as a cook, the same occupation for Wong in the Supreme Court ruling and other documents.

South Oregon Street at the turn of the 20th century was the heart of El Paso’s small Chinatown, full of boarding houses, restaurants and other businesses catering primarily to Chinese immigrant workers.

In October 1905, Wong returned to San Francisco from another trip to China, his first since the Supreme Court case seven years earlier, records show.

Frost, the American University law professor, found records that Wong later attempted to bring several of his sons from China to the United States.

His eldest son, Wong Yook Fun, arrived in San Francisco in 1910, but was soon departed when immigration officials ruled that they hadn’t proved they were related. Frost said the records indicate they actually were father and son. The eldest son never returned to the United States.

Wong Yook Sue arrived in the United States in 1924, stating that he was the third son of Wong Kim Ark, a U.S. citizen, and entitled to admission. He was initially denied entry but successfully appealed and was allowed to stay. Two other sons were admitted to the United States in the next two years.

In her research, Frost discovered that Wong Yook Sue admitted in 1960 that he had falsely claimed to be the son of Wong Kim Ark so he could enter the United States. He was among the thousands of “paper sons,” Chinese immigrants who falsely claimed to be the child of U.S. citizens in order to enter the country.

Wong Yook Sue made the admission through the Chinese Confession Program, which the United States conducted in the 1950s and ’60s to normalize the immigration status of Chinese people who entered the country fraudulently. The program was created from a fear that China’s Communist government might try to plant spies in the United States.

The “paper sons” program was an example of fraud that has long plagued a racist and often corrupt U.S. immigration system, Frost said.

“Our immigration system seems to be its own worst enemy because it creates this enormous bureaucracy that is self-defeating,” she said.

Lessons for today

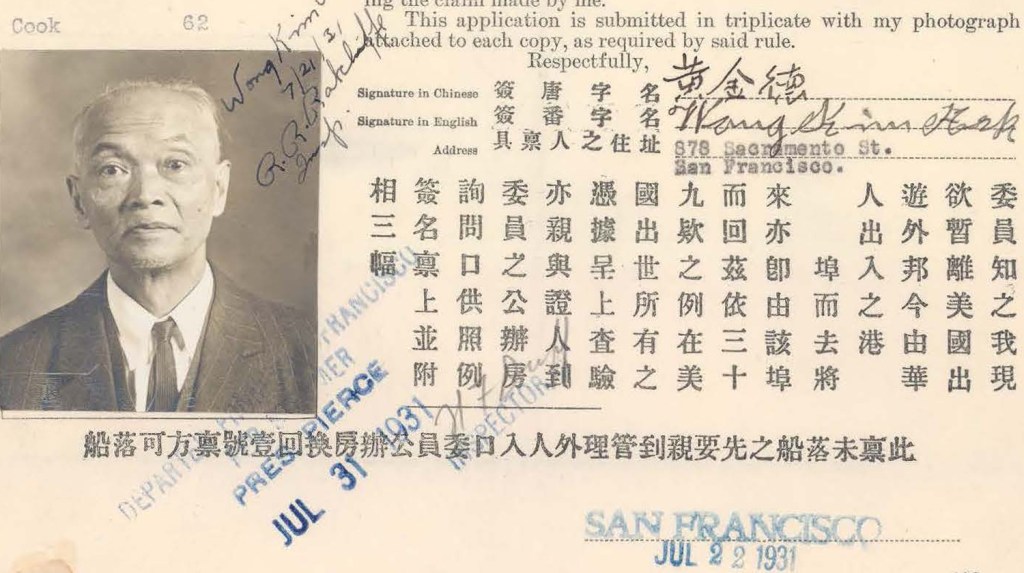

Wong Kim Ark returned to China in 1931, filing a document indicating that he would come back to the United States. He never did. It’s not clear when he died.

His legacy lives on. Wong Kim Ark’s legal battle ensured that all children born in the United States to immigrants would be citizens. That birthright citizenship protection has paved the future for tens of millions of people born to immigrant parents.

But attempts continue to reverse more than 120 years of settled law.

The Texas Republican Party 2022 platform approved June 16 calls for a constitutional amendment to “support a change to the 14th Amendment to eliminate ‘birth tourism’ or anchor babies by granting citizenship only to those with at least one biological parent who is a US citizen.”

Frost said the alarmist and racist language used to describe Chinese immigrants in the 19th and 20th centuries is similar to language used today concerning immigrants from Latin America, Africa and other areas. She said the impact of Chinese immigrants and their descendants should give pause to denunciations of those seeking to immigrate today.

“Does the U.S. regret the presence of Chinese immigrants today, even the fraudulent ‘paper sons?’ Of course not – they are the ‘model minority’ who worked hard and succeeded,” she said. “And in doing so helped build the United States. We should view would-be immigrants today as an asset for our country, not people to be feared and barred.”

This