Roger De Moor has presented his students with an emergency scenario many of them know well: Your 3-year-old has locked themselves in the bathroom. They’re panicking.

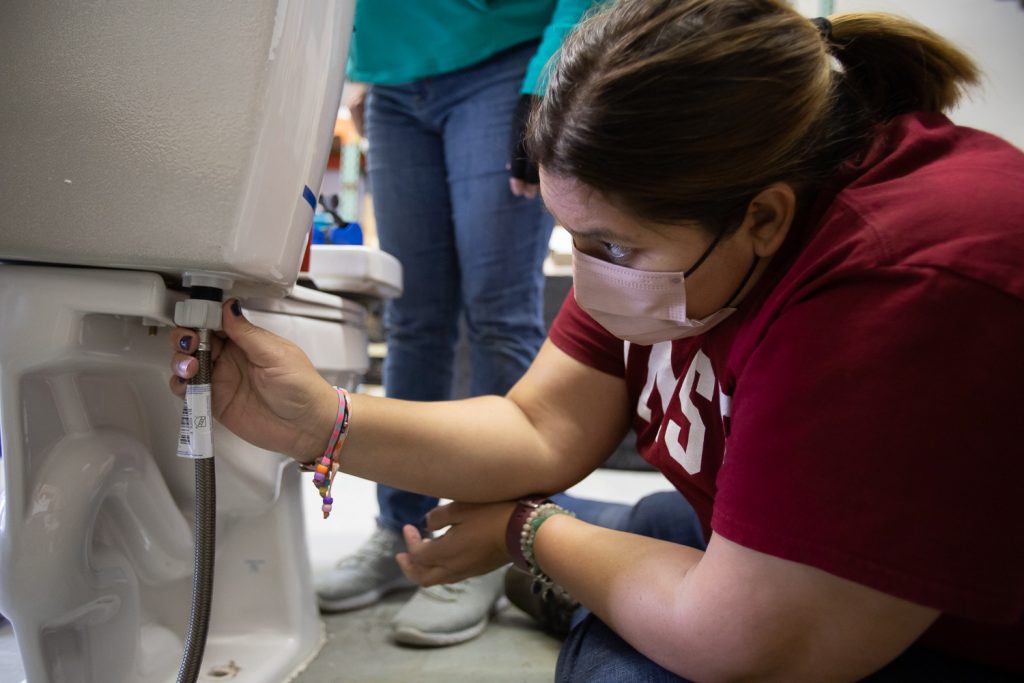

In a room that looks like a high school shop class, nine women walked up to a makeshift door and slid a small pick into the doorknob, searching for the groove that would open the lock.

“My teenager, she takes the keys,” said Kathy Chavez, whose daughter went through “the terrible teens” and used to lock the door to her room. Chavez’s cousin, Terri Garcia, held up the pick and grinned: “Not anymore.”

The cousins are single moms eager to rely less on Garcia’s aging father for help with home improvement tasks — and to save money. When Garcia walked from the model toilet, where she had just replaced a malfunctioning flapper valve to repair a leak, she shook her head. “Just to get a plumber to come out it’s a minimum of $50 to $90,” she said.

Over the course of two hours, the home-repair tasks grew more complicated. By the end, the students were stripping electrical wires and learning to fix power outlets.

These are the sorts of home problems that SHEbuilds, a national program with local affiliates, wants to help women solve. The El Paso class, along with Nailed It!, which offers similar skills training through Western Technical College, are collaborative initiatives new to El Paso that aim to boost women’s independence and help them save money on home emergencies that can be prohibitively expensive.

The classes are also meant to spark women’s interest in the construction trades, said Marisela Correa, the programs manager at Workforce Solutions Borderplex.

Entrepreneur opportunities

With women hit hardest by pandemic job losses, the organization has been searching for opportunities to help train women for new, better-paying jobs, she said. “We want to give women an opportunity to explore these fields and see if they’d be interested in going back to school and getting actually a certification.”

Correa sees ample opportunity for female entrepreneurship in the field, particularly with home improvement occupations.

“I’m a single mom. If I had to choose between a male and a female to come into my home and fix things in my house, I would 100% allow the woman to come into my home versus a man,” she said.

This is exactly what Yamel Cabello had in mind when she enrolled in SHEbuilds. As a single mother for 11 years, she’d experienced the discomfort first-hand of having an unknown man enter her home for repairs while she was alone with her children. She’s recently started to clean houses, and wants to add home repairs to the range of services she can offer — services she can charge more for than home cleaning.

“Coming from the culture that I come from, as a Mexican, we don’t expect feminine power doing these kinds of things,” she said. “But it’s more simple than everybody thinks it is. I think it’s important that women get involved in all these jobs instead of just trying to do, like, ‘lady things.’”

“We want to show what women are capable of in non-traditional sectors,” said De Moor, the executive director and program coordinator at SHEbuilds.

Infrastructure funding

President Joe Biden signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act into law in November. The law will funnel more than $1 trillion into projects involving roads, public transit, bridges, internet, and water and power systems. It promises hundreds of thousands of new construction jobs — so much so that the National Center for Construction Education and Research estimates the industry could see shortages of 1 to 2 million construction workers by 2025.

But if the current gender balance in construction trades persists, the jobs created by the infrastructure package will go almost exclusively to men.

In 2020, women held just 11% of construction jobs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics — the lowest female participation rate of any industry. In El Paso, it’s largely the same, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates.

Instead, women make up more than three-quarters of El Paso workers in the category of “health care and social assistance.” That category includes jobs like child care, where the median hourly pay is less than $9, compared to nearly $16 an hour for construction jobs. Nationally, more than nine in 10 child care workers are women.

Workforce Solutions has also listed a number of construction-related fields — among them, civil engineers, plumbers, electricians and construction equipment operators — as “hot jobs” in the region for 2022.

Given the small proportion of women working in construction, it might come as a surprise to learn it’s one of just two fields where El Paso women’s earnings outpace that of men’s, with a male-female pay gap of 162%.

That’s likely because a few high earners have dragged up the pay average for women, said Leila Melendez, CEO of Workforce Solutions Borderplex — most likely female business owners and engineers, rather than physical laborers.

So while this number probably doesn’t reflect the reality for most women working construction, it does hint at what women stand to gain if they enter it.

Karen Edmonston is the president of El Paso Chapter #248 of the National Association for Women in Construction, and has been working in the steel trade since 1973. In 1990, she started her own company, Area Iron & Steel Works. Today, the company brings in $3.4 million in sales each year.

“After 31 years in business, one of my competitors still says I belong in the kitchen,” Edmonston said. “If I had listened to those guys, I wouldn’t be where I am today.”

Of her 22-person staff, five are women, all of whom work in office positions. “I had a shop foreman who was a lady and the guys just ran all over her,” she said. “And then I had another time when I had a lady welder out there, and they just creamed her too.”

“I think sometimes it’s the mentality of the lady, if she’s not as tough as (the men) are.”

The toughness required in those jobs can be extreme. Patricia Carillo, also a member of NAWIC Chapter #248, remembers a time when she walked back to her truck from a work site. A coworker had smeared a crude pair of breasts in the dust of her drivers-side window.

Many of her male co-workers were embarrassed by the drawing, Carillo recalled, and offered to clean the window for her. She wouldn’t let them. “I wanted to prove the point that nothing was going to intimidate me,” she said. She drove her truck that way for a week.

“We could have done so much more”

In the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Meg Vasey saw an enormous opportunity to diversify the construction field. Vasey is the executive director of the California-based group Tradeswomen Inc., which aims to increase the number of women in construction trades.

As the bill made its way through Congress, Vasey was especially excited by language that would set requirements for the number of apprenticeships on construction projects funded through the infrastructure bill, which are meant to help women enter an industry notorious for its nepotism, she said.

She and other advocates had also pushed for “respectful workplace provisions” to encourage more inclusive worksite cultures for women, men of color and LGBTQ workers.

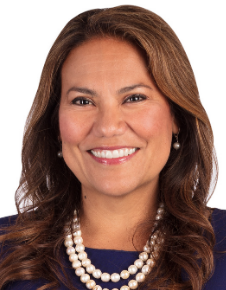

“We had a bill that was historic, and we were all very proud of it on the House side,” said U.S. Rep. Veronica Escobar, D-El Paso. “It really was very thoughtful in its approach to equity, not just for communities like ours — economically disadvantaged communities — but in terms of gender equity.”

The Senate, however, did not use the House’s version of the bill. “It was a huge disappointment,” said Escobar, who said that she and other Democrats nevertheless voted to pass the bill into law because it had bipartisan support.

None of the provisions that had excited Vasey made it into law, either. “We failed,” Vasey said simply. “The need for infrastructure funding is critical. So on that level, I’m very pleased. But in terms of the equity provisions inside of it, I really feel we could have done so much more.”

Gender equity in construction can still be improved, she said, if the Department of Labor’s Office of Federal Contract Compliance and its Office of Apprenticeships improve their enforcement of existing regulations governing workplace diversity.

Economists project the two pieces of legislation that make up Biden’s Build Back Better agenda will add an average 1.5 million jobs annually over the next decade. As it stands, just one of the two bills has passed. The Build Back Better Act, which in its current version promises major changes to the country’s social infrastructure, faces an uncertain path in the U.S. Senate.

Its provisions would create “care economy” jobs in fields like education, child care and elder care — all female-dominated industries. Vasey said many of the bill’s current components could also help more women enter construction — especially when it comes to increasing access to child care, which involves boosting pay for childcare workers.

“It creates an environment where women can go back to work,” Vasey said.

In its current version, the social infrastructure package also provides $2.8 billion to support apprenticeship programs, including about $850 million targeted to groups that are underrepresented in construction trades, according to an analysis by the group Chicago Women in Trades.

“Those of us who have been very strong proponents for the Build Back Better Act have been in part saying we want to build back better—with women,” Escobar said.

“Construction is a very hard nut to crack,” said Vasey, who worked as an electrician for decades, until her knees gave out and she decided to go to law school. “You’re asking contractors who work on very thin profit margins to change their idea of what a worker looks like.”

But other physically demanding and dangerous fields, such as law enforcement and fire fighting, still see more women than construction, she noted. “After 40 years … I expected to be in better company by now,” she said.

The construction industry can be hostile to women, but on that front, she said, it’s far from alone. “Clearly, the #MeToo movement exposed hostile work environments in the upper echelons of white collar work in America. It’s brutal on the construction site, but it’s brutal in a lot of places.”

And construction pays better than most, said Vasey, who after raising three sons on her electrician’s salary had enough money left over to enroll in law school. And, she noted, “there’s a sense of accomplishment. You’re building the bridges and the roads, and the refineries and the industrial complexes that run America.”

Despite the harassment she has experienced, Carillo is equally enthralled with the industry. Now an operations manager at El Paso’s PC Automated Controls, she is still just one of 11 women in a 68-person company — and the only woman that works out in the field.

“I love the smell of concrete,” she said. “I love the drywall.” Even when she’s in an office, she asks: “Sit me by the window so I can see the building grow.”

This article first appeared on El Paso Matters and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

![]()