Two asylum seekers from India who have been on a hunger strike at El Paso area immigration detention facilities for 75 days will be released soon, their lawyers said.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials have agreed to release Ajay Kumar, 33, and Gurjant Singh, 24, after they complete several days of refeeding at the agency’s El Paso Processing Center, lawyers Linda Corchado and Jessica Miles said.

“After he signed his release (documents), Ajay said namaste to each officer and looked at me with tears in his eyes,” Corchado said on Twitter. “’This road was long ma’am,’ he said. His is one voice in a broken system.”

Kumar and Singh were among four Indian asylum seekers who began hunger strikes on July 9 at the Otero County Processing Center, an ICE facility in southern New Mexico just outside El Paso that’s operated by a for-profit company. They had been held almost a year and were asking to be released while their cases were decided by immigration judges. They were moved to ICE’s El Paso Processing Center several days after beginning their hunger strikes.

Photo courtesy Jessica Miles

Gurjant Singh weighed 89 pounds on Wednesday, down from 126 when he started his hunger strike. Photo courtesy Jessica Miles

It was the second large hunger strike at El Paso ICE facilities this year. In January, nine Indian men began a hunger strike at Otero and were transferred to ICE’s El Paso facility, where they were force-fed for two weeks. Those men also sought to be freed while their immigration cases were decided.

Eventually, two of those men were released in April after refusing food for 74 days. Most of the other men were deported, lawyers have said.

In the latest hunger strike, ICE sought force-feeding orders from federal judges for the four men in August. The judicial force-feeding orders in El Paso this year have been shrouded in secrecy, as judges have barred public view of all but one of the case files.

The sole exception has been the case of Kumar, which U.S. District Judge Frank Montalvo partially unsealed in August at the request of the hunger striker’s lawyers. In the cases of Singh and another hunger striker who has asked not to be identified because he didn’t want his family to know he’s on a hunger strike, U.S. District Judge David Guaderrama opened an Aug. 16 court hearing to the public but has kept all records sealed. The case of the fourth recent hunger striker, who hasn’t been publicly identified, has been sealed by U.S. District Judge Philip Martinez.

Thirteen Indian asylum seekers have been force-fed this year after beginning hunger strikes at the Otero County Detention facility in southern New Mexico, just outside El Paso. Photo by Robert Moore.

Testimony in hearings last month showed that ICE obtained court orders Aug. 14 authorizing the agency to begin force-feeding the four hunger strikers. Nasogastric tubes were inserted through their noses, down their esophaguses and into their stomachs.

The United Nations has said that force-feeding detained and imprisoned hunger strikers is a form of torture. The practice is widely deemed as medically unethical, something that ICE physician Dr. Michelle Iglesias acknowledged in the two August hearings.

ICE officials have said force-feedings are justified when hunger strikes put the life of detainees at risk, and federal judges have repeatedly approved force-feeding orders.

ICE doctor’s role

Iglesias’ treatment of the hunger strikers – before, during and after their force-feeding – has been harshly criticized by the hunger strikers, their lawyers and an expert in health care for detained populations.

Her identity was masked in records filed in Kumar’s case, and in the two August court hearings she was identified only as “ICE doctor,” even when she testified. However, she was publicly identified at a February court hearing involving two of the earlier hunger strikers. She said she was a contract physician for ICE and maintained a family medical practice in El Paso.

In her testimony at the two August hearings, Iglesias described the involuntary insertion of a nasogastric tube as “uncomfortable.” Kumar, the only El Paso hunger striker allowed to testify at a public court hearing this year, had a far different description.

“The process of putting in the tubes was very painful, excruciatingly painful,” Kumar said through a Punjabi interpreter. “This was a question of my freedom, so I bore it.”

Kumar and Iglesias both testified that it took three attempts to insert the feeding tube.

On the first two attempts to place the feeding tube through his left nostril, X-rays showed that the tube coiled up in his esophagus, Iglesias testified. The tube was withdrawn each time. “When I put it in the right nostril, I was able to get it in the stomach without coiling,” Iglesias said.

On the first two attempts to place the feeding tube through his left nostril, X-rays showed that the tube coiled up in his esophagus, Iglesias testified. The tube was withdrawn each time. “When I put it in the right nostril, I was able to get it in the stomach without coiling,” Iglesias said.

She said she hadn’t seen tubes coil in previous force-feedings.

In his testimony, Kumar said he had bleeding in his nose and mouth during the three attempted insertions and had trouble breathing. After the two failed attempts, he said a nurse asked him to voluntarily drink a protein shake. “If you don’t drink this, we will put in this tube again,” Kumar recalled the nurse saying. He refused and the third insertion attempt was made.

Iglesias and Kumar also testified that the other three hunger strikers were in the room when Kumar underwent the procedure. Iglesias said the small medical facilities at ICE’s El Paso Processing Center left her no other choice.

Kumar said he bled during the insertion process and he believed ICE was trying to intimidate the other hunger strikers. Two hunger strikers from earlier this year said the nine Indian men were present at each insertion proceeding, which was often bloody.

Kumar testified that he witnessed the nasogastric tube insertion of his three fellow hunger strikers. One of the men, who hasn’t been publicly identified, stopped breathing during his procedure and had to be revived, Kumar testified. Lawyers said that man ended his hunger strike after that.

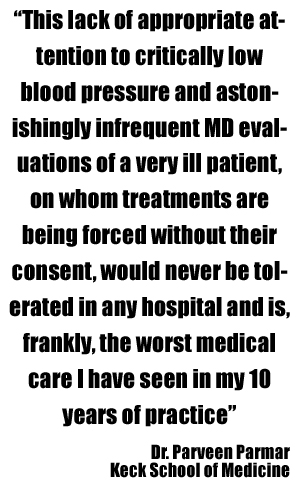

Dr. Parveen Parmar, a professor at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California who has experience providing health care in jails, reviewed Kumar’s medical records for his lawyers and wrote a scathing critique of his care that was submitted to the court.

“This lack of appropriate attention to critically low blood pressure and astonishingly infrequent MD evaluations of a very ill patient, on whom treatments are being forced without their consent, would never be tolerated in any hospital and is, frankly, the worst medical care I have seen in my 10 years of practice,” Parmar wrote.

Montalvo cited Parmar’s findings – which ICE didn’t dispute in its filings with the court – in a Sept. 12 opinion that was critical of the care afforded Kumar.

“It is troubling that Respondent (Kumar) was not brought to an independent doctor for immediate evaluation upon initiation of his hunger strike,” Montalvo wrote.

Montalvo criticized Iglesias, though not by name, for failing to follow up on the reason the nasogastric tube coiled in the first two insertion attempts. He also highlighted several other examples of poor care identified by Parma.

“It is the duty of the Government to provide adequate medical care, not just to keep Respondent (Kumar) alive,” Montalvo wrote.

Despite his criticism, Montalvo’s Sept. 12 order said ICE could legally force-feed Kumar and other hunger strikers after obtaining court orders. He suggested, but did not order, ICE to obtain independent medical evaluations of future hunger strikers before seeking court permission for force-feeding.

Differing fates for hunger strikers

The force-feedings for Kumar, Singh and the third hunger striker who has asked not to be identified ended on Sept. 5, 22 days after they began, according to court records and information from attorneys. All three men continued refusing to eat, their attorneys said.

During their hunger strikes, the men received support from a number of nonprofit groups, including the American Civil Liberties Union, the Detained Migrant Solidarity Committee, and Advocate Visitors with Immigrants in Detention in the Chihuahuan Desert.

Earlier this month, two of the four hunger strikers were deported to India, lawyers said. One man was in the 66th day of his hunger strike at the time, his lawyer Corchado said.

Iglesias “cleared him basically straight from her medical facility to the plane for India. He had not even had one meal,” Corchado testified.

In her testimony at the two hearings in August, Iglesias said a condition known as “refeeding syndrome” was a potentially lethal threat for people who resume eating after long periods of starvation. Such people require close medical attention as they resume eating, she said.

ICE officials didn’t immediately respond to questions of why one man was deported while nine weeks into a hunger strike and at risk of refeeding syndrome.

Iglesias told Singh and Kumar this week that she would sign release orders if they agreed to resume eating, lawyers Corchado and Miles said. The men asked for the commitment in writing from ICE. Kumar got that commitment on Friday, and Singh got it on Saturday, their lawyers said.

They have resumed eating and are being monitored for refeeding syndrome at the ICE’s El Paso Processing Center, Corchado and Miles said. They should be released within a week.

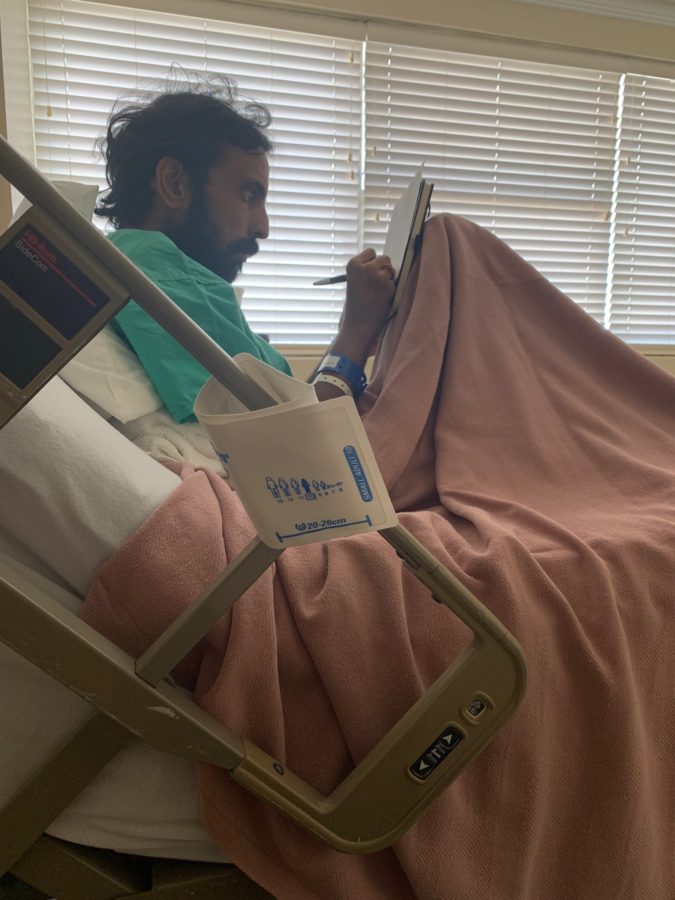

Ajay Kumar writing. Photo courtesy Linda Corchado.

Both men said they fled India to seek asylum in the United States because they were political activists and feared persecution or death if they stayed in their home country. Neither had lawyers during their immigration cases and their asylum claims were denied by judges. Both men now have lawyers and are appealing their asylum denials.

ICE has discretion to release or detain single adult asylum seekers while their cases are pending. Indians have said repeatedly that they feel that El Paso area ICE officials discriminate against them in detention decisions, an accusation ICE officials have denied.

Kumar and Singh both lost significant weight in their hunger strikes, but Singh’s condition seemed the most precarious. He weighed 89 pounds on Wednesday, down from 126 when he started his hunger strike, Miles said.

“I hope this is the last time that we have to do this. I hope that El Paso ICE will stop the harmful practice of force feeding,” she said. “I also hope that the injustices that led these men to stop eating will be addressed, that there will be an investigation into the across-the-board bond and asylum denials to Indian asylum seekers at Otero County Processing Center. Without access to justice, these men have to go to extremes to save their own lives. I never want to see another emaciated man begging for his freedom again.”

On Wednesday, Corchado made public a letter Kumar had written to the El Paso community, asking for help in his efforts to be free. He mentioned the Aug. 3 mass shooting in El Paso that killed 22 people. Police have said the gunman was targeting Hispanics and Mexican immigrants.

“I am a good citizen, and I am not a danger to people. I have no criminal record in India or in the United States. If saving/protecting one’s life and demanding freedom is a crime, then I have done it,” Kumar wrote. “I pray for the people who were killed in El Paso and pray that they rest in peace. I trust the people of El Paso and believe that they will help me gain my freedom. Thank you! El Paso Strong. I am strong.”