Zeke Peña, an illustrator and cartoonist has spent most of his work as an artist living on “la frontera,” the border, reflecting the reality and issues faced by Chicano and Mexican-American generations.

“I think about how the border identity is binary. It isn’t about this side or that side, it’s way more complicated. But that’s the beauty of it,” he says.

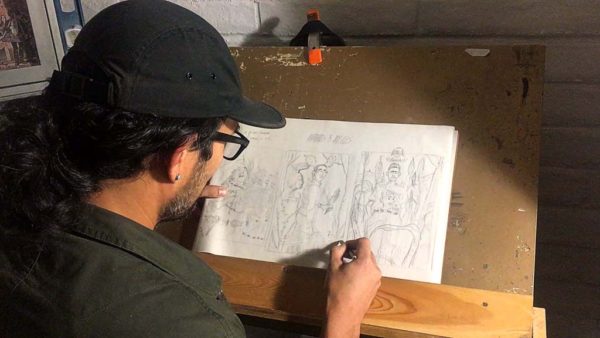

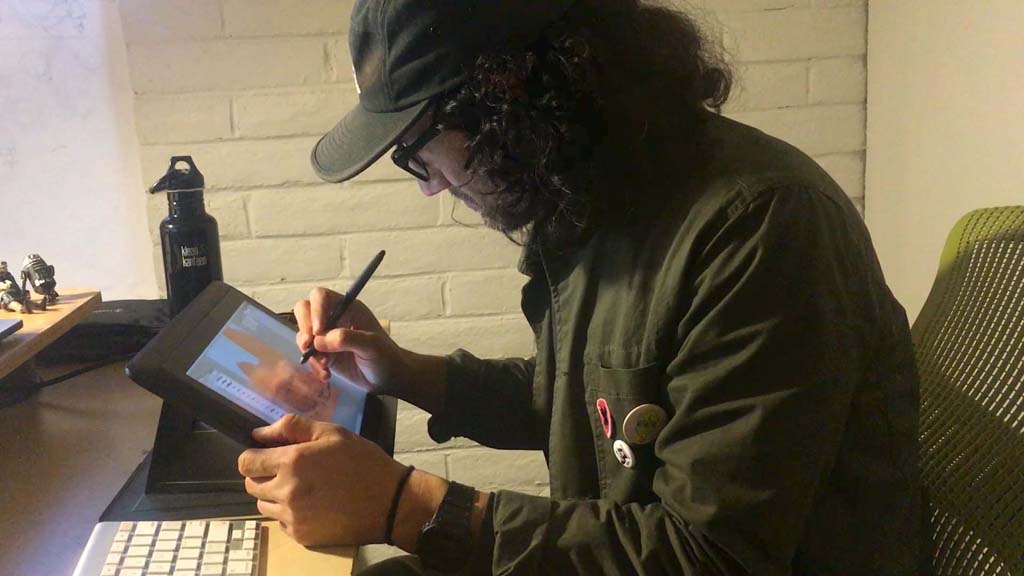

Illustrator/Cartoonist Zeke Peña in his studio. Photo credit: Jacqueline Aguirre

Sitting in battered, squeaky wood chair in front of a drafting table that displays his work in his studio, the 35-year-old Peña looks the part of a committed artist with his black-rimmed glasses and his shoulder-length dark curly hair and black ball cap. He has several buttons pinned to the pocket of his olive green shirt jacket displaying his sense of activism.

The Las Cruces native currently lives in neighboring city of El Paso. His nomadic cultural identity stems from his family roots asof farm workers from Mexico who immigrated to various farming communities on the U.S. side of the border, Peña proudly claims the title of border child with a strong U.S.-Chicano heritage.

He claims that although the experience of other border residents may be different from his life as a fronterizo who crosses often between Juarez and El Paso, they all share the same nomadic identity.

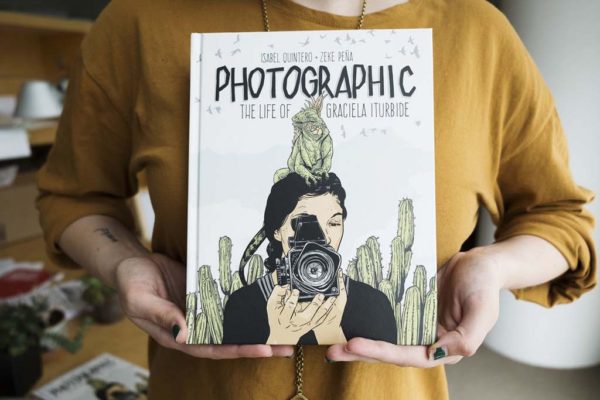

Zeke Peña’s previous work- a personal graphic biography of photographer Graciela Iturbide.

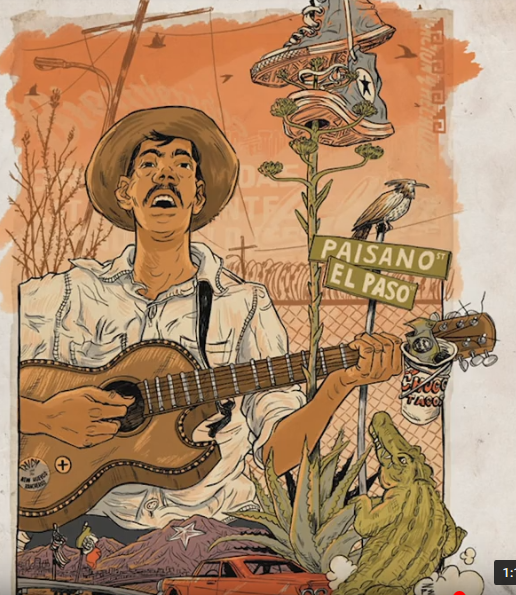

Peña’s illustrations focus on historical narratives about politics, social justice, national and cultural identities along the border.

His early stories were inspired by cartoons and comics and later matured into refined concepts inspired by ordinary border residents, activists, poets and theorists such as the Rio Grande Valley’s acclaimed Chicana writer Gloria Anzaldúa.

Peña says in his work he reflects on his personal border identity and how it relates to his community to produce resistencia (resistance) one cartoon at a time.

Peña sketching in his studio in Central El Paso. Photo credit: Jacqueline Aguirre

While Peña didn’t initially consider his work “border art,” he feels a responsibility to represent his community on the frontera. As a natural and organic response, Peña illustrates stories to shed light on issues of immigration, family separation, and the environment showing the faces of Mexican-American men, women and children of the borderland.

“I have to be sensitive to people’s stories and representing them to be sure that images of people in tent cities and people crossing rivers is with consent and care to who they are,” Peña says.

Image courtesy Zeke Pena

He says his storytelling focus is changing because of heightened civic engagement and activism on the border and nationally about Latino or Hispanic issues.

In January, Peña begins work on a new exhibit at his favorite space, which he refers to “el punto final,” the culmination point for his art – The Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts based at UT El Paso.

Working with UT El Paso art students, Peña will “create a bridge” between art and the community by installing a didactic exhibit to show through photos and illustrations how border residents think about air, water and land.

Kerry Doyle, director of the Rubin Center, says her mission over the past five years has been to bring art and concepts about the border to the gallery for an international conversation on contemporary art that includes working artists from all over the world.

“I think the reason that art is so important right now is because art is more about asking a question rather than making a statement,” she said.

Doyle has lived on both sides of the border for the past several years and has seen the growing militarization of the border in real-time. She views the border as a “physical manifestation of political polarization,” and attempts to blend local with international artist voices to keep the conversation about local and international borders flowing.

“It’s always a privilege to immerse (artists) in a border community one way or another. We give them information and they make art in response,” Doyle says.

Peña says his work has been inspired by “the thousands of people that have come before me in my community” as well as from outside artists that are creating art around border subjects.

“It’s self sustaining,” he says, “like a community.”