CD. JUAREZ – She remembers everything about that Thursday afternoon in 2004 at the cycling track of Ciudad Juarez. The training was going perfectly. She was confident about her speed, her movements, her pedaling. She was five-years-old and new to the cycling sport, but loved riding. The track was crowded and her parents were watching.

She is not sure what went wrong. A curve was coming. She panicked.

After her two-and-a-half hour training, Fernanda Polanco rests and rehydrates herself at the Juarez ciclopista. Fernanda came back a few weeks ago from the National Olympics bringing with her a bronze medal. (Estefanía Barrón/Journalism in July)

The crowd watched as Silvia Fernanda Polanco lost control of her bike, jumped off and grabbed on to another cyclist, then fell to the ground.

“Her calves were scrapped by the wheel,” Fernanda’s father, Gilberto Polanco, remembers. “When I got close to her to pick her up, I could smell her burned flesh.”

The accident left her unable to walk for a month, but did not stop her from cycling. Ten years later, 15-year-old Fernanda is one of the best young cyclists in Mexico, with two silver and four gold medals in the National Championship and a silver for her first year at the National Youth Olympics. She has competed nine consecutive years in the Copa Confederaciones (Confederation Cup), placing third twice, second three times and first place for four years in a row.

“I am the youngest member of the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juarez Team. Every year I have qualified for nationals. It’ll be my eleventh year in cycling.”

Fernanda, now a sophomore at Franklin High School in El Paso, learned to ride a bike when she was three. Her natural ability and potential were evident when her parents took off the training wheels that same year and started buying her bigger bikes soon after.

“She would go all around the neighborhood riding her huge bike,” Silvia Polanco, Fernanda’s mother, remembers. “She could not even reach the saddle, yet she would ride all around.”

By the time she was five, she had already joined art clubs, dance teams, and ballet classes but dropped the activities a few weeks later.

“She kept changing her mind,” said Silvia Polanco.

But the moment her parents saw her jump off her bike, her hair dirty and messy, wearing a first place medal around her neck after her first competition, they realized Fernanda’s interest in cycling was more than little girl’s curiosity. From that moment, the family decided to give Fernanda all their support no matter how difficult it would be.

“She was only five, and it was very hard at first,” Silvia Polanco said. “We would go to birthday parties and she could not eat cake, candy or drink soda. She started getting tired of it. At first I thought about letting her quit, but the season was about to start. I made her wait until July, after the championship, to drop if she wanted to.”

A year later, in July of 2004, Fernanda brought back home Juarez’s first gold medal from the National Championship.

“She did not really know what it meant for the rest of the people, but she really liked her medal. She wouldn’t let go of it. For her it was just something different. What could a six-year-old know about that?” said Silvia Polanco.

Fernanda’s mom is a housewife and her dad is a mechanic, but despite her achievements and her long cycling trajectory, she and her family had received little support from the government.

“I get many congratulatory messages, but I’ve never gotten a ‘hey how can we help you?’ or ‘do you need help with the flight tickets or something?’” Fernanda said.

The federal government sends an economic reward to each state when one of their competitors gets a medal in a national event, such as the Mexico National Championship, in which Fernanda has competed many times, always bringing home medal.

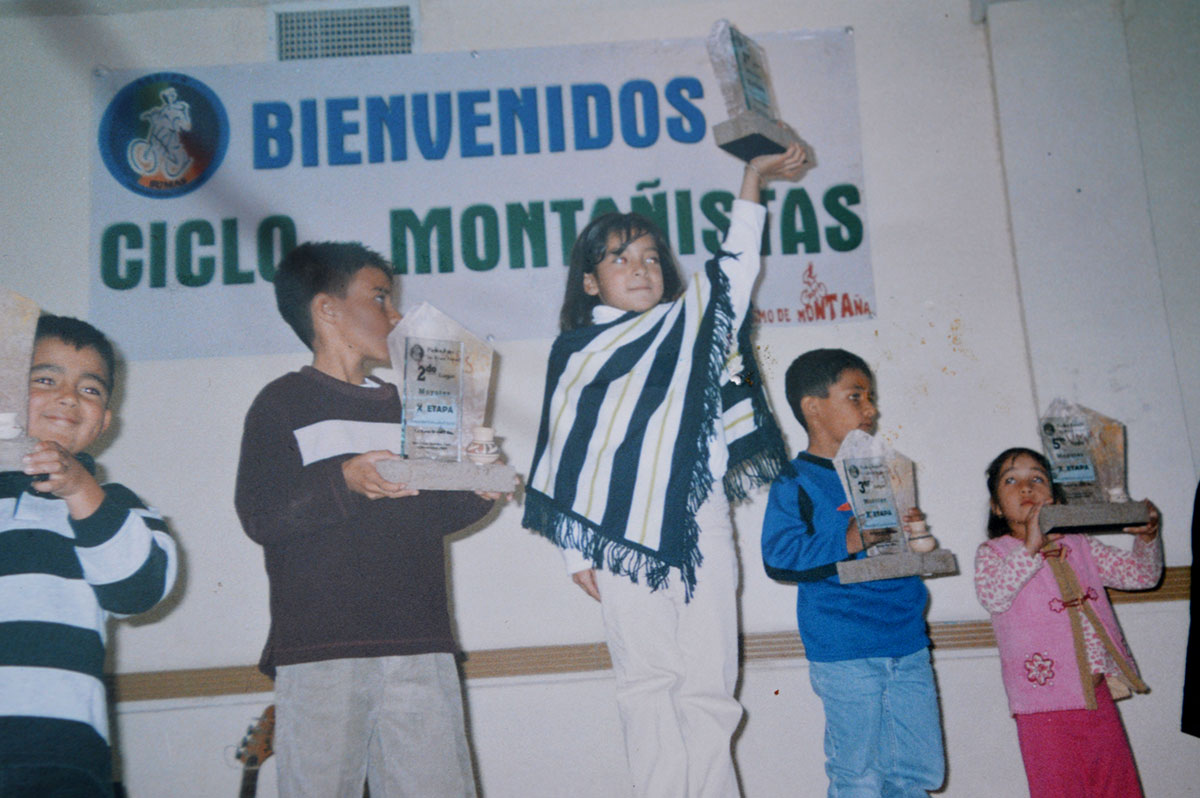

Fernanda Polanco proudly holds her fist place plaque in the 2005 Mountain Race State Championship. “She had to drop the mountain cycling team because the boys would bother her for being the only girl,” her mother said. (Courtesy of Fernanda Polanco)

“Fernanda barely got a scholarship for her athletic achievements last year. She has been winning for years. Where did all that money go?” asks Silvia Polanco explaining that her daughter received 2400 pesos, about $240 (U.S. dollars), every three months.

Fernanda, who was born in the U.S., crosses daily from her home here to attend Franklin High School in El Paso, were she earns A’s, belongs to the National Junior Honor Society, and was in the wrestling team until she was injured. She is not sure what she wants for her future, but she is interested in criminology.

Although keeping up with Fernanda’s career has not been easy, family unity has kept them together through good and bad times, stretching money as much as they can to attend tournaments in the state of Chihuahua and to pay for their daughter’s vitamins and sport’s beverages. Victoria, her 12-year-old sister, cheers at every competition and carries water for her.

This love motivates Fernanda to win every time she gets on her Specialized bike.

“We are all on this together. We had to learn together,” said Gilberto Polanco, who leaves work every day at 6 p.m. to go see Fernanda training at the Juarez Cyclopista. Silvia says she always waits for her daughter at the finish line.

“We want to experience each stage of her life, meet her boyfriends, watch her getting school achievements. All of that we want to enjoy it with her,” her father added.

__________

Editor’s note: This article was previously published by Writing the Fence.