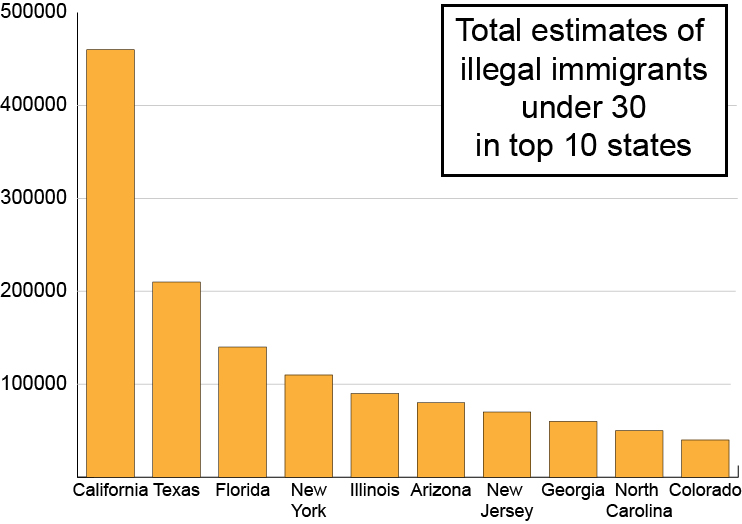

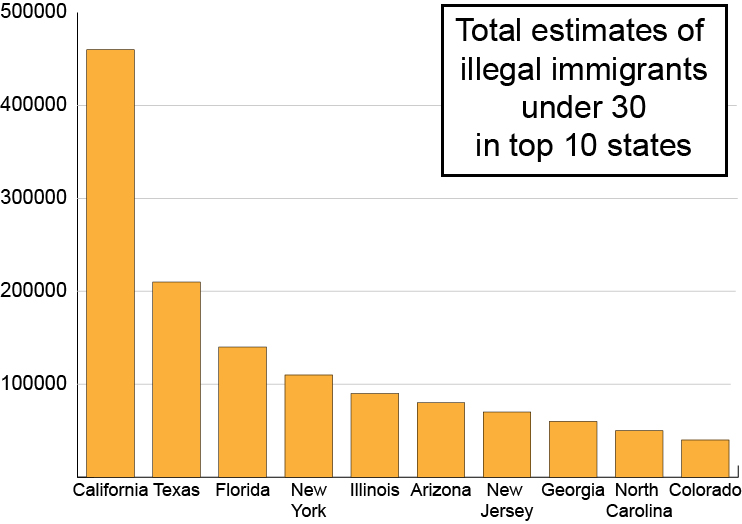

Migration Policy Institute analysis of 2006-08 and 2008-10 census data. Graphic by Matt Wettengel

The bus to the University of California at Los Angeles campus took two hours to travel a distance that would take 20 minutes by car.

Sofia Campos took this bus ride twice a day during her first two years of college. As an illegal immigrant born in Lima, Peru, and brought to the U.S. when she was 6 years old, Campos can’t legally obtain a driver’s license.

That’s just one of many inconveniences these students face when choosing to attend college.

“We pretend when we see a cop pass by that we don’t get scared,” Campos said. “Youth are having to grow up a lot faster. … Many of my fellow peers had to study through finals while their siblings or parents were going through deportation.”

It’s been a long journey for Campos, now 22, a recent UCLA graduate with a focus in international development studies and political science. She took three quarters off from school to work so she could pay tuition.

After five years, Campos accepted her degree on the same day President Barack Obama announced his plan to postpone deportation of young undocumented immigrants for at least two years and to allow them a work visa. Campos plans to pursue a master’s degree in urban planning this fall and will submit her application for the deferral program.

UCLA Labor Center Director Kent Wong said it’s a step in the right direction.

“This will result in a huge opportunity for over one million immigrant youth living in the United States,” Wong said. “The unfortunate reality has been that these students have grown up in this country, graduate from high school, many are attending and graduating from college and yet they cannot legally work in this country. Many of my students who get degrees are relegated to the life of underground economy.”

Undocumented students are offered in-state tuition in 12 states and only three of those – California, New Mexico and Texas – allow the students to apply for state financial aid.

Blanca Gamez, a recent graduate of the University of Nevada at Las Vegas, said the biggest obstacle she encountered was paying for school.

“Just for that reason, many undocumented individuals are deterred from applying,” Gamez, 23, said.

Her younger sister was born in the U.S., is a psychology major at UNLV and doesn’t face the same challenges Gamez does. At 7 months old, Gamez came to the United States from Alamos, Sonora, Mexico, with her aunt and uncle – legal U.S. residents – under the guise of being their child. An earlier attempt to cross the border with her mother failed.

State and university scholarships that don’t require students to submit a Social Security number are what helped Gamez graduate with a bachelor’s degree in political science and minor in English. She, too, is hoping to pursue a post-graduate degree.

Campos, co-chair of United We Dream, a national group of youth-led immigrant organizations, hopes to educate people about applying for the deferred action program. Many are fearful to apply because they have a lot to lose, so they need to know they have a support group vying for them, Campos said.

“We are more than willing to be a family together. We’re going to be pushing for larger immigration reform,” she said. “We are going to be pushing for more sustainable reform, not just for youth.”

_____

Editor’s note: This story was previously published on Scripps Howard Foundation Wire.