JOHNSON CITY, Tenn. — The bell rings. Science Hill High School students crowd the hallways. Among them, five international students head to English as a Second Language class, where they learn American culture, improve their reading and writing skills and get support for other courses.

Wilber, a ninth-grader with a big smile and an even bigger personality, is one of five students in the second-period class. When Wilber’s family relocated here years ago, he stayed in Mexico with his grandparents. Recently he moved to Johnson City from San Juan Cacahuatépec, México.

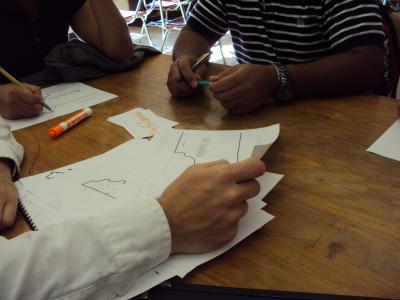

Students in Joe Hoffman's class learn about local geography. (Brittany Shope/El Nuevo Tennessean)

“School is a lot different there,” he says. “In México we have one teacher who teaches all of our classes. Here we have a different teacher for every subject. I like changing classes. I meet more people that way.”

He walks into the ESL classroom and sets his backpack on a chair. Another student follows and they begin to play-fight and banter with one another. A girl, the only female in this class, laughs at the two as she walks in, an excited look on her face. Two more students file in and everyone sits down at a square table.

There’s an excitement that doesn’t exist in most high school classrooms. A boy who recently arrived sits in the middle, the only Asian among four Hispanic students who seem to have taken him in. The four speak Spanish and laugh at one another. Wilber playfully slaps the newest arrival’s back and treats him as if he’s been with this group all year.

Teacher Joe Hoffman, arriving from his hallway duties, comes in smiling and the students start chatting with him eagerly. Today he’s teaching the five beginner students about communities in and around East Tennessee. As each student points out the cities of Johnson City, Bristol and Erwin, they laugh at one another for pronouncing their Rs awkwardly and confusing Kentucky with Virginia.

In any other classroom, making these mistakes in front of peers may be embarrassing. In the ESL classroom, there’s a cheerfulness and sense of community.

“Out there in their other classes, they’re often quiet and soft-spoken,” says Hoffman, one of two ESL teachers at Science Hill. “In here in ESL, they feel more comfortable and look forward to the one hour each day that they’re amongst peers they can relate to and identify with.”

The U.S. Department of Education projects that by 2015, some 30 percent of the children in U.S. schools will be learning English as a second language. The government estimates that 2.4 million school children who are national-origin minorities have limited English language skills that affect how they perform in school. As these students struggle with their inability to speak English fluently, they can fail many of their classes or drop out all together.

Hoffman asks his students to spell United States, and Wilber answers, “USA!” The other four students chuckle and someone else starts spelling United, “U-N-E…” They work together to get it spelled correctly and then take turns saying it out loud to practice their pronunciation.

Hoffman’s work with his students doesn’t end when they leave his classroom. He collaborates with other teachers in the school to make sure that the teachers and his ESL students are working together to help each other work through the language barrier.

“Mr. Hoffman is familiar with the subject matter and expectations I have for my students and will work with them, when time allows, in his ESL classes,” says Bryan Friddle, an algebra and psychology teacher at Science Hill. “If that is not possible, he will often come during his planning time and pull students out of my class during practice time to work with them one-on-one, to tutor them and help them be more successful.”

Some school systems have traveling ESL teachers who aren’t in each school every day, says Hoffman. Because he is in school every day, Hoffman interacts with his students and gets to know their personal needs and learning levels.

“I really get to know, interact and bond with each student individually,” says Hoffman. “I usually have them in my class for two or three years instead of just four and a half months.”

Hoffman’s students, like all ESL students in U.S. classrooms, are required to keep up with the same amount of schoolwork as their English-speaking peers while also learning the language.

While ESL students are working hard in their classes, the government is hard at work as well. Last year, President Barack Obama signed an executive order to renew and strengthen initiatives to increase academic achievement among Hispanic-American students. According to the White House, this was first signed by President George H.W. Bush and continued by Presidents Clinton and George W. Bush.

“Making sure we offer all our kids, regardless of race, a world-class education is more than a moral obligation, it’s an economic imperative if we want America to succeed in the 21st century,” Obama said in a White House press release. “But it’s not something that can fall to the Department of Education alone. It’s going to take all of us – public and private sector, teachers and principals, parents getting involved in their kids’ education, and students giving their best – because the farther they go in school, the farther they’ll go in life.”

Hoffman sees how ESL students must work even harder than their English-speaking classmates to pass their courses and meet educational requirements. During his second-period ESL class, there is no lack of enthusiasm for learning. Hoffman pulls out a map of the United States and all five students point to different states, shouting out their names. In these classes, students not only learn – they find inspiration.

“When I finish with school I want to go back to México and teach English,” says Wilber, whose brothers have lived in America for much longer and learned English at an early age.

As high school ESL classes prepare English-language learners for college and careers, they become an important key to student success.

“Without these programs, the students would be more isolated socially than they are – at school and within the community,” Hoffman says. “They would struggle more in their other classes – some would be lost. For many, their acquisition of English would be limited to language relating to work.”

The bell rings. Wilber puts his pencil in the front pocket of his backpack and follows his fellow students out into the hallway. The five students separate and head to their individual classes. Tomorrow, they’ll be reunited for the one hour of the day when they can be themselves and enjoy learning on the same level as their classmates.

_____

Editor’s note: This story was previously published on El Nuevo Tennessean