The following article by Shang Wang was published on NiemenLab.org on Aug. 20, 2015. It is reprinted here under a Creative Commons license.

31-year-old Rubén García Villalpando was shot twice in the chest this past March, after a traffic stop that police reports claimed turned into an altercation. Villalpando was unarmed at the time. According to news reports, he was also an undocumented immigrant who’d been living in the U.S. for the past 15 years.

This particular shooting was covered in English-language media. But what do we know about deaths during encounters with law enforcement that don’t make it into mainstream American news?

Encuentros Mortales, a Spanish-language open-source reporting project, is collecting public records and media reports of undocumented immigrants killed during interactions with law enforcement, starting from the year 2000, with a focus on the southern border of the U.S. It will also rely on crowdsourced submissions to fill in the gaps, mining Spanish-language news outlets along the border and promoting itself widely within Spanish-speaking communities. The site aims to be a “comprehensive, searchable, and impartial national database” that journalists, academics, and others can use to get a “better picture of the [U.S.] government’s activities.”

“I’ve seen reports about undocumented immigrants being killed,” the site’s creator, D. Brian Burghart, said. “And I’ve seen that the federal government basically refuses to answer questions on the topic. Major publications like The New York Times and others have done public records requests from all those federal agencies that have police powers on the border, and they’re not getting anywhere.”

At the moment, the site is a tiny team effort. To kickstart the database, Burghart — who is also the full-time editor of Reno News and Review — made 67 Freedom of Information Act requests to federal agencies, and over 200 other public records requests to all the counties along the U.S.-Mexico border in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. He’s assisted by a few college students as semi-regular researchers and a third researcher trained in combing through records request responses, who can also help with data entry if the number of records returned becomes overwhelming.

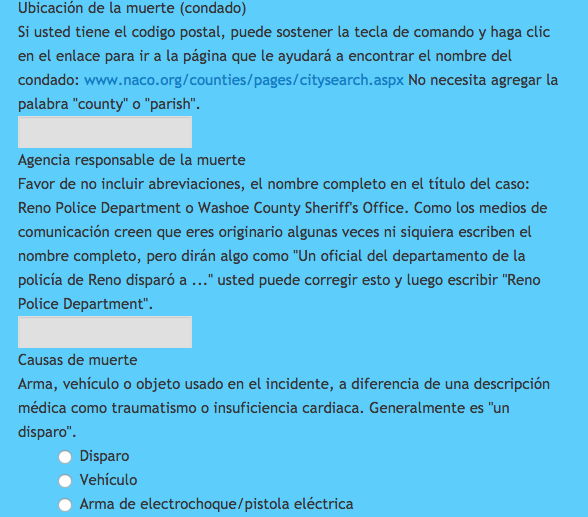

Right now, Encuentros Mortales has a placeholder site that will be revamped in the coming months to handle crowdsourcing. The new site will let anybody submit a record for inclusion in the database. Details on the circumstances surrounding each reported death will be collected in or translated into Spanish. The reporting tool will also be GPS-enabled, so submitters can enter coordinates for fatalities that occur at locations without official addresses.

All submissions will be individually fact-checked against police reports and/or reputable media reports whenever possible, said Burghart — though he suspects that, given the spotty nature of reporting on undocumented immigrants, some deaths will have to be marked as unverified.

Fact-checked records will live in a Google spreadsheet that anyone can download. Whenever possible, that spreadsheet will include not just information on the circumstances of the death, but also details such as whether charges were filed or whether the deceased had a known history of mental illness.

Encuentros Mortales is funded through a Masters Mediapreneurs Initiative “$12,000 geezer grant” from J-Lab. Some of the money has gone toward translations and paying a developer to build an improved website.

Encuentros Mortales has an English-language counterpart, Fatal Encounters, which Burghart created in response to what he saw as a lack of rigorous data on police killings. The FBI provides data on “justifiable homicides” via its Uniform Crime Report, but it relies on voluntary self-reporting from local and state agencies across the U.S. and has been criticized for inconsistency and undercounting. The Justice Department also released numbers in 2013, based on a nationwide survey of police departments, but its own review of the data found it to be a “significant underestimation.”

“Once I realized the federal government wasn’t keeping adequate statistics on people killed by police, I was offended,” Burghart said. “I thought it would be as simple as writing some 50 public records requests and then I would have the information I thought people deserved. It didn’t take me long to realize how naive I was.”

The Fatal Encounters database now includes fact-checked data on more than 8,000 killings, but Burghart estimates it is still only about 40 percent of its eventual size, as more public records from more states roll in or volunteers stumble across a missed incident. Verified deaths in the Fatal Encounters database that involve undocumented immigrants will be added to Encuentros Mortales.

Fatal Encounters is just one of many DIY efforts that aim to better document the consequences of police force in lieu of reliable official data (other frequently cited databases include Killed By Police and the Wikipedia page listing “killings by law enforcement officers in the United States“). Major news organizations have leaned heavily on Burghart’s data, as well as data from Killed by Police, for their own investigations and, in some cases, their own crowdsourced counting projects.

“Encuentros Mortales was an immediate favorite of our panel of judges, in large part because of Brian’s incredible track record with FatalEncounters.org,” Jan Schaffer, director of J-Lab, told me via email. “He built [Fatal Encounters] from scratch, using a lot of crowdsourced labor and contributions, and he’s perfectly okay with his data being scraped by the likes of the New York Times, The Guardian, and The Washington Post, which have all used it to build their police-involved homicide databases.”

The use of Spanish-language contributors to surface incidents along the Mexico-U.S. border, Schaffer added, “is likely right on the money.”

Still, Burghart is aware of the editorial and financial challenges of trying to build an impartial database. Fatal Encounters is funded entirely by donations, but with several other similar efforts out there now, such as The Guardian’s The Counted project, funding may be more difficult to come by.

While Burghart is hopeful that the crowdsourcing component of Encuentros Mortales will be fruitful and fast-moving, he isn’t sure how big or small the database will ultimately become, and he’s always wary of inflating the count. (Recently, for instance, he received some records on incidents involving people killed who fell just over the border, on the Mexico side.) Down the line, Burghart said, countries like Mexico could adopt some practices from Encuentros Mortales to build their own databases.