Kent Rinehart laughs as he and his classmates tackle the challenges of learning a new language. (Todd Brison/El Nuevo Tennessean)

By Todd Brison

JOHNSTON CITY, Tenn. – It is difficult for a parent to explain birth control to a child. That topic gets even more complicated when things are the other way around.

This is exactly the situation Spanish teacher Holly Melendez found herself in when she accompanied a Spanish-speaking friend to the doctor’s office.

“Even as poorly as I was interpreting, the other doctors asked me to come down and help them out with someone else,” Melendez said. “When I got there, a 6-year-old girl was trying to describe birth control to her mother. That sort of thing is not okay with me.”

Getting health care is complicated. There’s insurance, prescriptions, diagnosis and following the doctor’s orders, and even after all that, there’s no guarantee that sicknesses will be resolved.

It is very difficult, not only for the patient, but also for the physician attempting to help people who come looking for help. Trying to explain something like cancer treatments can be hard enough in a native language.

One attempt by East Tennessee State University to bridge the language gap is a class called “Spanish for Health Care Providers” that is taught by Melendez (pictured below). The trip that she took to the doctor that day is a big reason she is involved in this class.

“There is a barrier there with the language difference,” Melendez said. “It can be torn down if the physician makes an effort.”

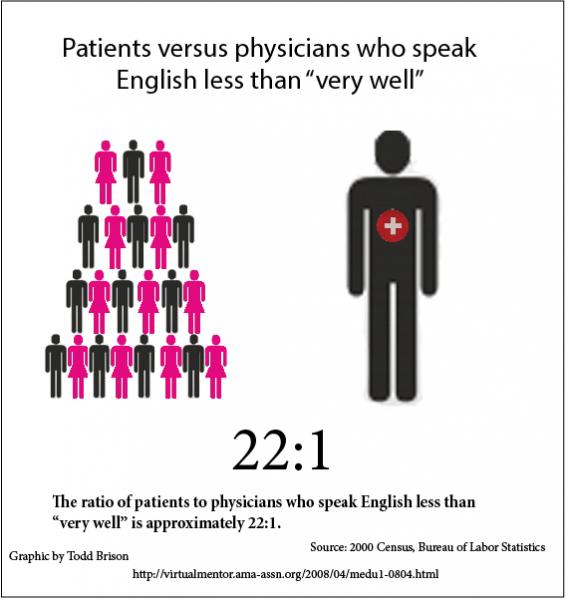

Source: 2000 Census Bureau of Labor Statistics.

English-speaking physicians in general have a difficult time communicating with Spanish-speaking people, especially if an interpreter is not available. It can be difficult for the doctor to even understand a patient’s symptoms, much less diagnose and attempt to treat them.

John Barrowclough, a doctor who works in the emergency room at a hospital in Morristown, quickly learned he was going to have to speak some basic Spanish. According to Barrowclough, if a physician doesn’t know the basic questions and answers, that slows the process down too much.

“We used to have an interpreter in Morristown available to us, but we’ve had to cut back,” Barrowclough said. “But even with an interpreter, it can be difficult.”

Barrowclough has been in Morristown for 20 years and says he has seen the Hispanic population grow substantially. According to him, it is important that a doctor do all he or she can to avoid having to go through an outside source. The privacy of a patient is important.

“Very often you just have to resort to the best you can do,” Barrowclough said. “And sometimes that involves a family or friend, which can be awkward.”

Most of the students in Melendez’s class plan to be doctors one day. They already have experience with language differences in the medical field and have gone through the difficulty of attempting to communicate in two languages. Although some clinics have phone lines with interpreters, those don’t always work.

“I had to interpret once when our phones [at work] went out,” said Emma Isarg, a student in one of the classes. “I tried to tell a woman that her baby was… facing the wrong way in the womb, so I definitely want to continue to learn the language.”

Kent Starkweather is another student taking the class so he can make a difference. As an undergraduate student at Centre College, Starkweather studied abroad in Central America. In that time, he spent his days with three Spanish-speaking families and worked at an orphanage in San Pedro Sula, Honduras. There, he learned the reality of living in a third-world country. Once he returned to Nashville to work, Starkweather was not as happy as he had been overseas.

“I realized that while I could make a good living, I was not helping people the way that I thought I could,” Starkweather said. “So I went back to school, [and] got my pre-reqs for medical school.”

Starkweather says his time in another country influenced him to dream of opening a clinic in Central America to give people the opportunity for heath care.

The class is what’s known as an “elective enrichment class,” meaning that while students don’t get any credit hours for showing up, they may put the class on their transcripts and resumes in the future.

The two levels of the class meet for 45 minutes each. Level one is for students with little to no Spanish experience. In this class, students laugh as they translate or interpret things incorrectly, but are quickly learning the language. They take notes on common medical words. Melendez believes the practice of speaking the language out loud will begin to ingrain the words in their memory.

Holly Melendez teaching the class “Spanish for Health Care Providers." (Todd Brison/El Nuevo Tennessean)

The level two class focuses mostly on conversations. These students are already comfortable with the basics of the language, so they mostly practice the back-and-forth of a formal conversation. This can enable them to dig deeper into the symptoms of a patient and try to get to the root of them.

Students who show up for classes are generally laid-back and participate constantly. Even though they get no closer to a degree with this class, they all have reasons for being there.

“I want to have a better relationship with all my patients in all lifestyles,” said Kent Rinehart, a level-one student.

According to the students, even if an interpreter is present, some of the information can still be lost. Melendez says that even if the physician is not fluent, his or her attempt to speak Spanish can put the patient more at ease.

Although the language barrier is difficult to get around, sometimes there are other issues as well. Hispanic and Latino people occasionally have cultural differences that are harder to explain. Some Spanish-speaking people believe that sickness is caused by sins in a family’s ancestry, as opposed to any actual virus, Melendez said.

“In some bigger Hispanic communities in America, there are even witch doctors that have come into practice that people will go to instead,” Melendez said. “The cultural differences can be so extreme.”

Along with that come the misgivings about going to the doctor that all people have. Many will not go to the doctor in hopes that the symptoms will go away by themselves, thinking if the disease is not acknowledged, it will not exist.

Though this issue is nationwide, the program at ETSU seems to be making progress.

“Sometimes we would only have one or two students as things got busy,” Melendez said. “But this group has been bigger and better about all showing up…they really are interested in being here.”