Borderland Man – ebook conveys the hope that teens damaged by violence and desperation can heal

|

EL PASO – Ector Joel Acosta studies biochemistry and physics at the University of Texas at El Paso and plans to apply to medical school to become a dermatologist, but for now he has adopted a new identity – Borderland Man. In this new role, Acosta, 21, is now a published Latino writer and his first book Rise of the Borderland Man is for sale online. Acosta began writing the fictional account of a young man living in the borderland along the divide between El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico a year ago. Frustrated by the long and tedious process of finding a publisher, he published the novel as an e-book this year. “I was always keeping my mind on something – chess, writing, and art,” said Acosta who is a junior at UTEP.

Author sees new hope for Ciudad Juarez, ground zero for violence in the drug war

|

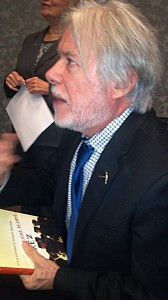

EL PASO – Ciudad Juarez has been “ground zero” for the violence raging in Mexico over the past half decade according to Ricardo Ainsle, a psychologist-psychoanalyst and author of the book The Fight to Save Juarez: Life in the Heart of Mexico’s Drug War. “Close to 60,000 lives have been claimed by this brutal drug war in Juarez and the future of Mexico’s drug war has gone global,” Ainsle said at a lecture at the University of Texas at El Paso October 22. To combat the drug cartels, the Mexican government sent 12,500 federal army police to the city, which represented 20 percent of all troops nationwide, he said. Ainsle added that the number of drug war-related causalities in Ciudad Juarez during the same period of time was 60,000 and represented 20 percent of the national casualties. “Nearly 20 percent of the country’s drug-related executions have taken place in Juarez, a city that can be as unforgiving as the hardest place on earth,” said Ainsle, who is known for using documentary films to depict subjects of cultural interest.

Juárez violence down 74 percent from 2010 peak

|

EL PASO – The word “partnership” was frequently used at the round table discussion of “Security Along the U.S.-Mexico Border” to explain what it takes to counter terrorism. This event was one of the many sessions of the 9th annual International Association For Intelligence Education (IAFIE) conference at the University of Texas at El Paso Wednesday. Five government officials of various agencies, such as the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) spoke in the panel. UTEP’s Vice-Provost Michael Smith began the session as the moderator. “This is a topic of keen interest obviously in El Paso and along the border region,” Smith said.

The Sun City’s nightlife rocks with the electronic-dance music that left Juarez

|

EL PASO – This city on the U.S.- Mexico border known for the strong Mexican-American culture experienced a dramatic growth spurt in music and entertainment in the past two years as nightlife fizzled in violence-plagued Cd. Juarez. “Many people expected the Juarez violence to spill over the border, but the only thing that spilled over that border was the real electro nightlife,” said Silver IsReal, head of Estylow Junktion clothing design. Juarez’s nightclubs such as Hardpop and Morocos concert halls were host to many shows that attracted well-known DJ’s. When the violence in Juarez began to increase, many El Pasoans stopped crossing the border to see those shows and the nightlife followed them north.

Businesses that migrated to El Paso still maintain their Juarez roots

|

EL PASO – The violence in Ciudad Juarez has had a huge impact in the cross-border area economy in recent years as businesses relocated here to become successful enterprises. The emigrating business owners, however, did not sever all ties to Juarez. The drug war and the climate of criminality it spawned took a huge toll on the Mexican economy, closing down businesses, chasing away clientele and most importantly stemming cash flow. This caused a large number of establishments to slash prices, cut jobs and eventually just close down. Many Mexican investors took a leap of faith and transferred their assets across the border to find a safe environment where their business would flourish.

Examples of courageous journalism are not so far from home

|

WASHINGTON – I strongly believe in the common phrase “everything happens for a reason,” and entering the fall internship at the Scripps Howard Foundation Wire fits the expression perfectly. Not only did I arrive here during Hispanic Heritage Month, making the transition from El Paso to Washington a little easier, but I also got the opportunity to witness two brave female reporters from El Diario de Juarez receive the Knight International Journalism Award from the International Center for Journalists. Rocío Idalia Gallegos Rodríguez and Sandra Rodríguez Nieto earned master’s degrees in journalism at the University of Texas at El Paso, my hometown university where I am majoring in multimedia journalism. We also happen to share a mentor, Zita Arocha, senior lecturer and director of the university’s online magazine, Borderzine.com. Gallegos and Nieto’s passion for journalism has led them to risk their lives every day, living and reporting in Juarez, a city ruled by corruption and impunity.

Surviving Juárez: Besieged residents and businesses devise strategies to stay safe in the violence-plagued city

|

Lea esta historia en español

CIUDAD JUÁREZ – María, a mother of four children and business owner, says her family has had to adopt “survival” measures to protect itself from the crushing daily violence plaguing her city. “We had to install a system of cameras that we monitor from home through the Internet,” said María, 54, who requested that her last name, details of her family and name of her businesses not be disclosed. This was after her family had to pay a “quota” when several of its businesses were targets of extortion, one family member was victim of an “express kidnapping,” and they realized their businesses were under constant surveillance by criminals. Subsequently, the family has contracted a security guard and installed alarms. By early afternoon, they lock the doors of their businesses and, as soon it starts to get dark, open the door only for known customers. They also removed business ads from the telephone directory and switched business and private telephone numbers to unlisted numbers.

Juarez coach now trains long-distance runners at UTEP

|

EL PASO – The violence that overwhelms daily life in Ciudad Juarez didn’t stop Pedro Lopez from helping others pursue the dream of becoming world-class runners. But now he dreams of the American dream. “The violence in Juarez is crazy. It became a crazy city. I remember when I was young and I could go out at whatever time and come back home late and not have any problem.

Juarez violence pushes a pastor and his flock across the border

|

EL PASO – Because of a lawless environment in Juarez in which churches are forced to pay protection money to gangsters or else suffer terrible consequences, the congregation of the Centro Cristiano Familiar Vencedores church felt threatened. Gunshots would regularly disturb services and Pastor Ramiro Macias’ church didn’t know what to expect when strangers appeared at the church door. Macias recalled recently that family dinners would be interrupted by the sound of gunfire in the neighborhood and the doorbell of his house rang at 3 a.m. on a regular basis. Not knowing what they wanted or why, he wouldn’t open the door and his family endured the sleepless nights in fear. The murder of a church member was the dreadful, final act of violence that motivated him to move his family and his church to El Paso.

A young man struggles to rebuild his life after Juarez gunmen murder his father

|

EL PASO — Norberto Lee’s tranquil life was abruptly struck with tragedy when his father was shot and killed by masked gunmen in front of their place of business in Juarez after he refused to pay protection money to gangsters. For months his father had been receiving phone calls demanding payoffs. “The calls began after my dad arrived from a trip, but he only told one of my brothers who then told my mom and then she told me. I told the rest of my siblings and we thought it was best for him to come to El Paso,” said Lee. His father came to stay in El Paso for 10 days but felt uneasy and was unable to stay any longer.

Pickets and hunger strikers demand a kidnapped family’s safe return

|

EL PASO — The Spanish words on white poster-board picket signs carried by Nancy Gonzalez cry out for “Justice and peace for Cd. Juarez.”

To the left of Gonzalez, on a busy downtown sidewalk Selfa Chew holds up a poster with a blood-red handprint overlapping a peaceful white dove. Person after person walk by, some hesitant and others curious as they scan through the words of rage on the posters. Then they continue on with their day. Every Friday from 2p.m. to 3 p.m., a group of individuals gathers in front of the Mexican Consulate building in downtown El Paso to remind the community of the assassinations and kidnappings of innocent people taking place right across the bridge in Cd.

Tales of kindness, trust and courage give voice to civic pride in Juarez

|

EL PASO — A passer-by helping out an elderly woman transit a busy avenue, a young man treating a homeless man to lunch, and organizations assisting those in need, are some stories that are told everyday in Crónicas de Héroes. In a city where residents are used to hearing bad news from local media every day about the violence-torn city of Ciudad Juarez, a new project is bringing out untold stories of unsung heroes. Crónicas de Héroes, or Hero Chronicles, reports the stories of Juarenses helping fellow Juarenses in everyday life at www.juarez.heroreports.org, and these examples of human kindness are reported by the citizens themselves. As local media focuses on the unfortunate situation Juarez is suffering through, its residents now have a website where they may report any valiant, or noble act of kindness they may witness. “The campaign attempts to inject positive energy and change from the citizens, and finally recover the civic pride, give rise to optimism and bring back the spirit of courage that has characterized the inhabitants of this city,” said Yesica Guerra, Manager of Crónicas de Héroes.

Juárez business finds new life across the border

|

EL PASO – Drug-war violence has crippled the economy of Cd. Juárez sending many business owners packing along with their customers, to the safer sister city across the border. El Paso has become the beneficiary of that middle-class migration since the criminal activity began to escalate in 2008. Ke’ Flauta, for example, a restaurant in west El Paso, is one of many businesses that has fled from its original location in Juárez. “Unfortunately, Juárez has gotten hit very badly with the violence. The economy is greatly affected and there are scary threats from extortionists against businesses all the time,” said Raul Aguilar, owner of Ke’ Flauta.

Juarez/Warez: Why quibble?

|

EL PASO – It had been a year since I’d last visited Juarez, considered the most dangerous city in the world because of unrelenting drug violence. After crossing the international bridge from EL Paso, I drove into a city under siege, past armed Mexican soldiers and army trucks lining the principal avenue leading to Juarez’s once-bustling central business district. Later at lunch, at Barrigas restaurant, a friend very much in the know shrugged and put down his fork as he explained, “The city government thought a strong military presence in this area would bring the businesses back,” he said, matter-of-factly. “And?” I asked. “It hasn’t worked,” he said, flashing an ironic smile and returning to his shrimp and steak. While he and the other friends my husband and I had lunch with last week seemed unfazed by this in-your-face show of military force on Juarez streets, the sight of so many soldiers with BIG guns left me feeling uneasy, queasy and anxious about the future of a once booming border city and important gateway to the U.S.

When I saw the soldiers strolling along with their M-16’s, a sign I’d seen on a wall in El Paso flashed across my mind like a news ticker on a TV screen: “Warez,” said the block-letter sign, a reference to Mexico’s ongoing drug war, a battle many politicians insist is not a war or even an insurgency, as Secretary of State Hilary Clinton has called it in public.

Businesses abandon a troubled Juárez as they follow customers to El Paso

|

Editor’s Note – This is another in a continuing series of Borderzine articles on the migration to the U.S. of Mexican middle-class professionals and business owners as a result of the drug-war violence along the border. We call this transfer of people and resources, the largest since the Mexican Revolution, the Mexodus. EL PASO — With a black apron around his waist and a headset on his head, the expatriated Mexican teenager places the payment for a lunch meal in the cash-register just as the drive-through starts beeping to place the next order. “When my dad came here we didn’t had any money, no money at all,” said Jose Antonio Argueta, Jr., 19. “Me and my sister had to pay everything, the house, the cars everything we had.” With a serious tone, Argueta tells how his family struggled to establish their restaurant Burritos Tony here. “My dad started working at minimum wage earning maybe like two hundred a week.”

Argueta has been working at Burritos Tony for more than a year.

Women in need find a haven at the Frontera Women’s Foundation

|

EL PASO, Texas – A few basics of daily life like laundry detergent, toiletries and some medical essentials such as new dentures help 11 families with 30 children stay on track at a lower valley non-profit homeless shelter. The Reynolds house shelters families –mostly women and their children– who have fled from domestic violence in Juarez and who need some help getting back on their feet. This low-key shelter opened its doors 20 years ago when Director Dorothy Truax’s mother inherited her parent’s house. “The time she inherited it I had a brother who was working with homeless families and individuals and he used to bring them home to mom when he couldn’t find enough space. When she got this home she thought it would be a perfect place for the families.”

Throughout the last year-and-a-half the Reynolds house has housed an increase in families fleeing economic problems and the violence in Juarez. The majority of the residents, however, are there because of domestic violence.