Griselda Reyna, never imagined she would be fleeing a group of armed men who had just kidnapped and murdered her two sons.

She knew she would be killed if she stayed in Ciudad Juarez. And that would leave her three young daughters without a mother.

Reyna, 42, grabbed her daughters, a trash bag full of clothes, and never looked back.

She has lived in the United States since July 2013. She worries every day about being deported, separated from her children, and if she would survive a return to Mexico.

Reyna is among millions of Mexican and Central American women who’ve fled to the United States, seeking refuge from deadly violence or economic insecurity.

Some have uncertain status as political refugees, which could change at any time. More than five million did not enter the U.S. legally. Because of their status, they live in a twilight zone surrounded by harsh realities. They have little or no rights with employers. Every day, they live in fear of being assaulted or robbed. And at any time, they could be arrested and separated from their families, leaving them both economically and emotionally devastated.

Millions of women like Reyna endure the hardships of living in the U.S. because that may be better than persecution, exploitation, and even death in their home countries.

No protections

Many of the undocumented workers and refugees come from countries plagued by violence and drug trafficking. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security reported in December 2014 “of the 486,651 apprehensions nationwide, 468,407 of those apprehensions were of individuals from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.”

That includes many “family units” – individuals apprehended with a family member – and “unaccompanied alien children.” The number of family unit apprehensions along the U.S.-Mexico border increased from 14,855 in fiscal 2013 to 68,445 in fiscal 2014. Over the same time, the number of unaccompanied alien children who were apprehended rose from 38,759 to 68,541.

Among those are millions of undocumented women – some of the most vulnerable workers in U.S. society.

They receive none of the protections that the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination based on race, color religion, sex, or national origin, or the Equal Pay Act of 1963, which prohibits wage disparity based on gender.

Undocumented workers often earn less than U.S. citizens in the same jobs, but undocumented women typically earn even less than their male counterparts.

According to a Pew Hispanic Center report, only 58 percent of undocumented women work in the U.S. compared to 98 percent of undocumented men.

The demand for cheap labor in the U.S. and the desperation of undocumented women who need to support their families create the ideal environment for exploitation by U.S. employers.

Targets for abuse and low pay

Undocumented women often have no other option but to take low-end jobs. For the most part, they provide household services for families, housekeeping, and care for children and elderly dependents.

The PHC report also stated that over 392,000 of undocumented immigrants worked in private households in 2008.

Undocumented women working in the U.S. are faced with minimal wages for long hours, no access to healthcare, no paid time off, unfair treatment, sexual harassment, rape and abuse.

Employers or companies that pay undocumented employees in cash can avoid labor laws.

Employees who speak up against an abusive employer may risk being reported to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. And that could result in arrest and deportation. Most undocumented women have no practical way to enforce their rights as employees and employers know that.

Eduardo Beckett, immigration attorney in El Paso, said undocumented women are oftentimes poor and uneducated. And that makes them more likely targets for sexism and minimal pay.

“I doubt that a corporation or employer would want to pay these women a good wage – quite the opposite,” Beckett said. “They would want to exploit these women because the employers know they’re hungry, vulnerable, and are too afraid to speak up.”

Contributions to the economy

A Southern Poverty Law Center study on undocumented women concluded that legalizing undocumented workers would raise the U.S. gross domestic product by $1.5 trillion over a decade. The study also warned that if all 10.8 million undocumented immigrants living on U.S. soil were deported, the economy would decline by $2.6 trillion over a decade. That figure does not include the substantial costs of such a massive deportation.

Each year, undocumented immigrants contribute as much as $1.5 billion to the Medicare system and $7 billion to the Social Security system even though they will never be able to collect benefits upon retirement, the study reported.

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission estimated in 2009 that the cost of health services and benefits provided to undocumented immigrants was $96 million.

A U.S. General Accounting Office report found that the actual cost of educating undocumented students remains unclear because most states lack actual enrollment figures.

The National Center for Education Statistics claims there may be resistance from undocumented students who refuse to provide the information for censuses out of fear of authority or discrimination.

But U.S. Rep. Beto O’Rourke, D-El Paso, said the daily lives of many U.S. citizens are made better by immigrant labor.

But there is a price.

Ethics and economics

“At what moral cost? Is it considered a norm to accept a system where some people’s labors and lives are worth less than others?” O’Rourke asked.

O’Rourke said that paying undocumented workers less than minimum wage – for jobs that people in the U.S. don’t want to work – raises ethical questions. Employers, he said, benefit from sharply reduced labor costs and consumers enjoy the benefit of reduced savings.

“It is seen in the restaurants that we eat at, the supermarkets that we shop at, and even the houses that we live in,” he said.

The Southern Poverty Law Center report stated that undocumented women play a vital role in the economy, “bringing a wealth of fruits, vegetables, meats, grains, nuts and processed food to our markets and restaurants like clockwork.”

The report noted that farmers depend on undocumented immigrants, which federal officials estimate make up 60 percent of the nation’s agricultural workers. Almost a quarter of the workers who butcher and process meat, poultry and fish are undocumented. About one out of five cooks are undocumented, and more than a quarter of the dishwashers are undocumented.

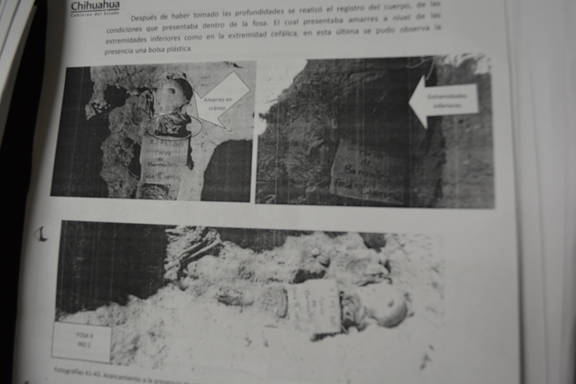

Forensic file of where Reyna’s sons’ bodies were found.

Living in fear

Still grieving over the loss of her sons, Reyna now wakes up everyday worried that she might lose her daughters as well.

For now, she is a political refugee. But that will change in August. At that time, Reyna expects to join the ranks of undocumented workers in the U.S. She believes she doesn’t have a choice.

“I came to the U.S. because I was afraid of the people who killed my sons,” Reyna said. “I’m afraid I’ll be killed if sent back because the people who took my sons know who I am and will kill me.”

In January, her sons were discovered in clandestine graves in the Juarez Valley, one of the deadliest places in Mexico.

Rogelio, 19, was a college student. His brother 16, was still in high school.

If deported, her daughters would be left alone in the U.S. And she worries that she wouldn’t survive a return to Mexico.

“I’m going to live with the pain of losing them for the rest of my life,” Reyna said. “But I have to keep moving forward for my daughters.”

Reyna has been outspoken about her story on TV and in print, talking to media and newspaper outlets in El Paso, Texas, and worries this has also angered whoever killed her sons.

“I know the Mexican government was involved because they haven’t done anything in regards to the pressure that I’ve put on them to find those that murdered my sons,” Reyna said.

Seeking asylum

She arrived at the Paso del Norte Bridge between El Paso and Juarez seeking political asylum in July 2013. She was required to make a statement and answer a series of questions before she was allowed to temporarily stay in the country.

Among the interview questions, she was required to prove credible fear, under the Sustaining Burden Clause in the Immigration and Nationality Act, Section 208 (b)(ii).

“Sustaining burden” means what the applicants says is credible, persuasive and demonstrates that they do, in fact, qualify as refugees.

“Credible fear” indicates that applicants have a genuine and reasonable fear of persecution inflicted by their governments or by a group their governments cannot or will not control.

The Credibility Determination Clause (Sec. 208 (b)(iii)) states that the immigration judge may decide that applicants qualify based on their demeanor, candor, or responsiveness, as well as the “inherent plausibility and consistency” between their written and oral statements.

Reyna initially was denied political asylum because she could not identify exactly who killed her sons and who was threatening her soon afterwards.

“People think that the drug cartels and Mexican government are two different entities that go against each other, but oftentimes they’re working together,” Reyna said. “Or people on the streets take advantage of the violence that goes on knowing they can get away with it. It could be anyone, I just don’t know who did it.”

Critical moments

Beckett, the immigration attorney, said that many people who apply for political asylum do not understand the importance of their initial statements.

“U.S. Customs and Border Protection will base their evaluations on what was said the very instant you apply for political asylum, so it is very important to know what to say and how to articulate it clearly,” Beckett said.

Language barriers and cultural differences make it difficult to communicate messages effectively and many women are turned away, Beckett said.

Beckett appealed Reyna’s case and a judge granted her limited political asylum. She is required to return to Mexico in August.

For now, Reyna is stuck in a legal limbo for the next two months with no permanent right to remain in the country. She’s a single mother in a foreign country, with no one to turn to.

Her case is just one of the thousands of asylum requests made by Mexican citizens and Central Americans in recent years.

More than 35,000 people applied for asylum based on credible fear in 2013, according to the American Immigration Council. But only about 10,000 were granted asylum.

As a single mother and because of her uncertain status, Reyna faces difficulty finding work, unfair employment conditions, sexual harassment, language barriers, discrimination, and limited access to healthcare.

Exchanging comfort for safety

But it’s a struggle she would rather endure. It’s better, she said, than fearing for her life in Mexico.

Reyna said she went from living comfortably in a three-bedroom house in Mexico, “where everyone had a bed,” to “living in a small trailer and sleeping in one room on a full size mattress in the U.S.”

“But at least here we actually sleep at night,” she said.

She currently works as a housekeeper to provide for her three daughters. They live in San Elizario, a rural Texas town along the Rio Grande, just southeast of El Paso, where the girls attend local schools.

Beckett is trying to reopen Reyna’s case. In the meantime, Reyna and her girls hope they can stay in the U.S.

“I have to keep moving forward and living,” Reyna said. “I have to try to give my daughters a better future.”

Crossing over

For many Mexican women, crossing the border is part of a daily routine.

More than 6.5 million pedestrians crossed the three bridges that link the two cities of El Paso and Juarez in 2014, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation. El Paso is ranked as the second-busiest port of entry into the country by passenger volume. Many of those pedestrians cross the border to work jobs in the U.S., buy groceries, or go to school.

Crossing the Paso del Norte International Bridge was routine for Patricia Moreno. She never imagined that one day she would be handcuffed and forced to submit to a body search. Agents with U.S. Customs and Border Protection even accessed information on her cell phone. The 56-year-old woman was accused of working illegally in El Paso.

For Moreno, it was an experience she would never forget.

“They called people from my contacts,” said Moreno, who, fearing retaliation, asked that she not be identified by her real name. “They came back and told me they had supposedly spoken to my employer, who had apparently spoken highly of me.”

It is generally unlawful for the government to confiscate personal property, unless there is probable cause in a criminal case or if officials have obtained a search warrant. However, both U.S. and foreign citizens report that CBP agents routinely confiscate their property, including electronics, without any explanation.

Beckett claims that CBP agents violate the privacy of pedestrians and motorists when they examine personal photos and files on their electronics.

The legality of the practice is being challenged, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. Generally, law enforcement officers can search through files on laptops and phones, and make copies.

Foreign citizens crossing the border do have some rights. They are protected by the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which protects against “unreasonable” searches and seizures by the government. A person cannot be singled out based solely on their race, national origin, religion, sex, or ethnicity.

Border exception to Constitution

But there is a “border search exception” to the Fourth Amendment that allows CBP agents and immigration officials more authority to conduct “reasonable” searches and seizures of property without a warrant or probable cause along the border.

“They have a right to inspect and make a determination if a person is admissible or not, and deport people on right on the spot,” Beckett said.

Moreno was kept in an interrogation room for over eight hours. She was told that if she admitted guilt, she would be released sooner and her visa status would not be taken away.

“I knew they were lying to me …” Moreno said. “It was very intimidating, but I didn’t admit to their false accusations.”

Beckett states that it is a common practice for CBP agents to use trickery, intimidation, and pressure to compel non-U.S. citizens to admit to their accusations under oath.

“Sometimes people are so vulnerable that they admit to these charges in order to get out of there as quickly as possible,” Beckett said. “At that point they’re deported based on wrongful determination.”

Depending on the agent’s determination, a person can be deported and refused entry into the U.S. from up to one to five years.

If a foreign citizen is detained, they also have rights under the Fifth Amendment. They have a right to remain silent and not answer questions. But according to the ACLU, exercising that right may make agents more suspicious, which could lead to further questioning and a prolonged detention. How long an officer may detain an individual is unclear.

“The system is broken”

CBP agents also have discretion to interrogate and pressure individuals to answer any questions.

During Moreno’s eight hours of questioning, she was stripped of her belongings, and subjected to an invasive body search.

“The female CBP agent put her hands down my bra,” Moreno said. “It was disturbing and made me very uncomfortable.”

Beckett said there needs to be more oversight of CBP agents.

“The system is broken,” Beckett said.

A risky commute

Moreno is a widow and single mother. She is struggling to put her two daughters through college.

“I want them to have an education, a better life,” Moreno said.

Working as a housekeeper in El Paso, where the pay is better, is the only way she can afford their tuition. In Juarez, it would take her a week to earn what she makes in one day in El Paso.

But commuting to work in El Paso has its costs.

Moreno has been robbed twice while riding a bus from her house to the international bridge. The first time, she was hit on the back of the head with a pistol.

“They took my purse and all of my belongings,” Moreno said. “They were probably just gangsters who knew they could get away with it.”

For the time being, Moreno lives and works in the shadows of U.S. culture. She exists in a world filed with insecurity, abuse, and exploitation.

But that world also offers her children more opportunities for an education and a brighter future.

So Moreno remains in the shadows.

Slipping Through the Gaps

The uncertainty is over for Carmen Salas.

She’s one of the lucky few. She can stay permanently in the U.S.

Salas, 47, married her husband after working in the U.S. without documentation for four years. When they got married, she had no idea that he was born in El Paso and a U.S. citizen.

She was able to become a legal resident. And life quickly changed.

Her weekly salary as a housekeeper nearly doubled after she became a legal resident. Today, she can earn up to $70 a day. She and her husband worked hard but have enjoyed a good life. They raised three sons who are now adults with families of their own.

That’s a world apart from the life she was willing to risk everything to leave behind in Mexico.

Limited options

Salas embarked on the most dangerous journey of her life, at 15, with an older sister. She said she knew that walking the 300-mile trip across the arid Chihuahuan Desert was her only option.

“We didn’t have clothes,” Salas said. “We were 13 brothers and sisters and my parents could barely afford to feed us, let alone clothe us.”

She risked being robbed or raped along the way. Almost anyone could have been a threat: the “coyotes” who guided other migrants through the treacherous terrain, robbers, government officials – and even other migrants.

She had no security. She left behind her father, brothers, and the community that had always protected her. She and her sister relied on each other for support and protection.

In the face of danger, the girls knew they had only two options: to run or hide.

“We would have never survived an assault by a man,” Salas recalled. “We knew that we were good at running and hiding, so I think that’s why we were able to survive the trip as two young girls.”

The Rio Grande was both the last obstacle to overcome and a place of peril. Stories of what happened to women there were well-known. Men would gather at the river’s crossing to wait for women who were weak and tired. They would then offer to help them cross the river for $50. Oftentimes, sex was requested as a form of payment. Sometimes, women were just assaulted.

But, in 1982, Salas and her sister made it across safely.

Exploitation may come at an even higher cost today, said Yesenia Leon, a U.S. Border Patrol agent.

“Oftentimes, a smuggler will have a set price of $3,000 but once they’ve crossed the border they’ll ask for more money and hold the person ransom until they get it,” Leon said.

In the field, Leon has seen more men than women making the trip. She said she understands why.

“It is very difficult as a woman to make that trip due to the amount of rapes and kidnappings that occur,” Leon said.

An Amnesty International report estimated that six out of every 10 migrant women from Central America are sexually assaulted during their journey to the United States. Other reports suggest that figure may be even higher, and that some women take birth control pills so they won’t get pregnant if they’re raped.

Marcela Benson, another border patrol agent who works with Leon, suggested another reason why many women may not make the trek.

“What probably deters a woman from crossing over is leaving her children behind,” Benson said. “Then there’s enduring three to five days in the desert until finding an actual road or highway.”

Exploited in the new land

When Salas made it across the Rio Grande, she faced a new set of problems.

She no longer feared for her life. But she needed to find a job in a country where she didn’t speak the language.

Salas eventually found a job working as a housekeeper. Her employers, she said, took advantage of her status as an undocumented worker.

“They would at times prohibit me from opening the fridge. I don’t know how they expected me to work if I wasn’t allowed to eat,” Salas said.

Other bosses were much the same.

“Every household that I worked for treated me like I was worthless or beneath them,” Salas said.

Constantly scrutinized, yelled at, and blamed for things she did not do, Salas said she felt like she had no value.

“I just wanted to find a job where they would be able to treat me like an actual person,” she recalled.

That day came – after she became a legal resident.