Life in the Creole region of the Caribbean

FORT-DE-FRANCE, Martinique — Bonjour ! Sa’w fè? Please allow me to introduce myself. I am a former aid worker, journalist, musician and all-around n’er-do-well who lives in Martinique, an island with a history, people, and language most people know very little about. The booming influence in the United States of all things Hispanic dwarfs our knowledge of the Caribbean’s Creole region, even though the latter is geographically closer to our shores than most of Latin America.

The suburbs of Fort-de-France, the capital of Martinique, with the legendary Mount Pelée looming in the distance.

Photo courtesy of Stacy Marie-Luce, Tanisha Photography.

Like the other islands that form this diaspora of former slave colonies, Martinique is much more than a Club Med beach or the obligatory “…and the Caribbean” tacked on to discussions about Latin America. First, unlike, say, Saint Lucia or Trinidad and Tobago, Martinique is not a nation; its status as part of France could best be compared not to Puerto Rico’s status as a U.S. territory but rather to Hawaii’s statehood. Martinicans have full voting representation in France, but also have a limited degree of autonomy in running their affairs—a topic of controversy ever since Martinique emerged after World War II from a brutal French-run apartheid regime that had ruled since the abolition of slavery in 1848.

(See French translation below. Voir la traduction en Français ci-dessous)

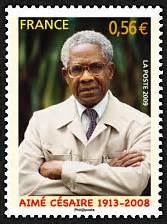

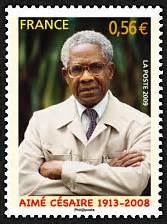

Most Americans might not have heard of Martinican leader Aimé Cesaire, but even his former adversary France today honors him with a postage stamp.

That brings us to Aimé Césaire, the pride of Martinique, and the greatest civil rights leader you’ve never heard of. An author, poet, and political leader, he was a towering figure in the Caribbean and Africa for more than half a century, but he is virtually unknown in the United States.

Césaire navigated Martinique through the troubled waters of the post-colonial period with an extraordinary combination of rage and guile. He started off as a communist and an advocate for independence, then eventually abandoned both for a more pragmatic approach, denouncing colonialism et every turn while at the same time twisting the arms of the French behind the scenes to cut the best deals he could for Martinique. He served as mayor of the capital of Fort-de-France for an astonishing 55 years, somehow keeping the peace between the island’s social divisions and power brokers, including the dominant black population, a mulatto population higher on the social scale, a small but economically formidable group of French expatriates, and what are known as the “bekés,” the white descendants of plantation owners who dominate the island’s economy even today.

Last year was the centennial of Césaire’s birth (he died in 2008 at the age of 94), and I had the privilege of performing with a musical group that accompanied readings of some of his most famous speeches. His tirades against colonialism would have made Malcom X seem moderate, and yet all the while he was making sure streets got paved and carrying out the other mundane tasks of a city administration. His efforts were not in vain: Martinique today has its problems—crippling strikes, stagnating tourism, and widespread unemployment — but it also has one of the highest per capita GDP rates in the Caribbean, functional modern infrastructure and, yes, great beaches.

Martinique also has the sad distinction of having been the site of one of the worst natural disasters in human history that, once again, almost no one knows about (including me, before I came here). The eruption of the Mount Pelée volcano in 1902 destroyed the city of Saint-Pierre and killed practically the entire population of about 30,000 people. One of the only survivors was a prisoner who had the good fortune to be held in an underground cell, and hence protected from the apocalypse over his head. Martinican legend, steeped in Catholicism, has it that he had been jailed for stealing a loaf of bread. No one is sure if that’s true, but we do know that he spent the rest of his life traveling with the Barnum-Bailey circus, billed as the sole survivor of the catastrophe.

Finally, Martinique is part of a linguistic phenomenon that, again, you’ve probably never heard of. Most Martinicans only spoke Creole when Césaire took office in the 1940s, but he taught himself the language of the oppressors and proceeded to condemn them in a French so erudite that it would have made Voltaire proud. Inspired by their leader and finally given access to education by the French, the entire Martinican population became bilingual within a generation. Creole lives on, of course, and residents are quick to point out that their version is quite different from that of other islands. In Haiti, for example, “How are you?” is “Sa’k pasé?”, whereas in Martinique it is “Sa’w fé?”— the greeting with which I started today’s blog post. In future blog posts I’ll cover the topics I touched on today and much more, from language to race to what it’s like being an American—there are very few of us — living here.

In closing, though, I’ll share the answer to the question above. You’ll need it if you come here. It’s “Sa ka maché!” – “I’m doing fine!”

David Einhorn has worked as a journalist for Knight-Ridder newspapers and as an international development worker with the U.S. Peace Corps., Inter-American Development Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He has worked and lived overseas in such countries as Paraguay and Haiti. He is also a jazz bassist and today works with Caribbean jazz artists such as Reginald Policard of Haiti and Luther Francois of Saint Lucia. He currently lives with his family in Martinique.

La vie dans la Caraïbe Créole

(Translated by Pascale Marie-Luce)

FORT-DE-FRANCE, Martinique – Bonjour ! Sa’w fè ? Permettez-moi de me présenter. Ancien travailleur humanitaire, journaliste, musicien, bon à rien, je vis aujourd’hui en Martinique, une île qui possède une histoire, un peuple, une langue dont la plupart des gens savent très peu de choses. Aux Etats-Unis, l’influence croissante de tout ce qui est hispanique éclipse notre connaissance de la Caraïbe créole, même si cette dernière est géographiquement plus près de nos côtes que la majeure partie de l’Amérique Latine.

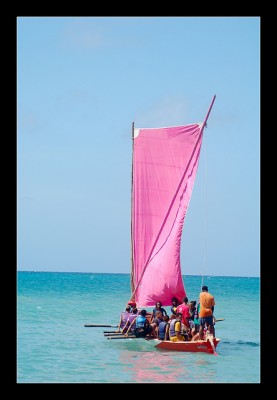

Sailing class for local high school students in Martinique.

Photo courtesy Rudy Glili, RRPG Photography.

Comme la plupart de ces autres îles qui constituent cette diaspora d’anciennes colonies esclavagistes, la Martinique c’est bien plus qu’une plage du Club Med ou que le fameux « …et la Caraïbe » que l’on se sent obligé d’ajouter aux discussions sur l’Amérique Latine. Premièrement, contrairement à Sainte-Lucie par exemple, ou à Trinidad et Tobago, la Martinique n’est pas une nation. Son statut de département français serait davantage comparable, non pas au statut de territoire des Etats-Unis de Porto-Rico, mais plutôt à celui de l’état d’Hawaii. Les Martiniquais ont les pleins droits de vote en France, mais ont également un degré d’autonomie limité dans la gestion de leurs affaires. C’est d’ailleurs un sujet de controverse depuis que la Martinique a émergé, après la seconde guerre mondiale, d’un régime d’apartheid brutal qui avait été instauré par les Français depuis l’abolition de l’esclavage en 1848.

Voilà qui nous amène à Aimé Césaire : la fierté de la Martinique et le plus grand leader des droits civiques dont vous n’ayez jamais entendu parler. Ecrivain, poète et dirigeant politique, il fut une figure imposante de la Caraïbe et d’Afrique pendant plus d’un demi-siècle, mais est pratiquement inconnu aux Etats-Unis.

Most Americans might not have heard of Martinican leader Aimé Cesaire, but even his former adversary France today honors him with a postage stamp.

Césaire a conduit la Martinique sur les eaux troubles de la période post-coloniale avec une extraordinaire combinaison de rage et de ruse. Il a commencé en tant que communiste et défenseur de l’indépendance, pour finalement abandonner les deux en faveur d’une approche plus pragmatique, dénonçant à la moindre occasion le colonialisme, tout en forçant subtilement la main aux Français afin d’obtenir les meilleurs accords possibles pour la Martinique.

Il fut maire de la capitale, Fort-de-France, pendant une période extraordinaire de 55 ans, réussissant d’une façon ou d’une autre, à maintenir la paix au sein des différentes couches sociales et des différentes forces au pouvoir de l’île : la population noire majoritaire, une population mulâtre, plus élevée sur l’échelle sociale, un groupe d’expatriés Français, minoritaire mais économiquement puissant, et ceux qui sont connus sous le nom de « békés » : les descendants blancs des anciens propriétaires de plantations qui, aujourd’hui encore, dominent l’économie de l’île.

L’année dernière la Martinique fêtait le centenaire de la naissance d’Aimé Césaire (il est mort en 2008 à l’âge de 94 ans) et j’ai eu le privilège de jouer avec un groupe de musiciens qui accompagnaient des lectures de certains de ses discours les plus connus. Ses tirades contre le colonialisme auraient fait passer Malcom X pour quelqu’un de modéré. Pourtant, dans le même temps, il s’assurait que les rues étaient pavées et menait à bien toutes les autres tâches ordinaires qu’engendre la gestion d’une ville. Ces efforts n’ont pas été vains : aujourd’hui, la Martinique a certes ses problèmes (des grèves qui paralysent le pays, un tourisme qui peine à décoller et un chômage étendu à toutes les couches de la population), mais elle possède également l’un des PIB par habitant les plus élevés de la Caraïbe, des infrastructures fonctionnelles et modernes et…en effet, de magnifiques plages.

La Martinique se distingue également tristement pour avoir été le site de l’une des pires catastrophes naturelles de l’histoire de l’humanité que là encore, personne ne connaît (y compris moi avant que je ne vienne y vivre). L’éruption de la montagne pelée en 1902 a détruit la ville de Saint-Pierre et tué pratiquement toute la population d’environ 30 000 personnes. L’un des uniques survivants était un prisonnier qui avait eu la bonne fortune d’être détenu dans un cachot souterrain, ce qui l’a protégé de l’apocalypse qui se déroulait au-dessus de sa tête. La légende martiniquaise, fortement ancrée dans la religion catholique, veut qu’il ait été emprisonné pour avoir volé un morceau de pain. Personne ne sait avec certitude si cette histoire est vraie, mais ce que l’on sait c’est qu’il a passé le reste de sa vie à voyager avec le cirque Barnum-Bailey, exhibé comme l’unique survivant de la catastrophe.

Enfin, la Martinique fait partie d’un phénomène linguistique dont, là encore, vous n’avez probablement jamais entendu parler. La plupart des Martiniquais ne parlaient que le créole quand Aimé Césaire fut élu en 1940, mais lui, il apprit la langue de l’oppresseur, puis s’attacha à le condamner dans un français tellement érudit qu’il aurait fait la fierté de Voltaire. Inspirés par leur leader et obtenant finalement des Français l’accès à l’éducation, les Martiniquais devinrent bilingues en une génération. Le créole continue d’exister, bien sûr, et les habitants sont prompts à signaler que leur version de cette langue est différente de celle des autres îles. En Haïti par exemple, « Comment allez-vous ? » se dit « Sa’k pasé ? », alors qu’en Martinique, cela se dit « Sa’w fè ? » (C’est la salutation avec laquelle j’ai commencé le billet d’aujourd’hui.) Dans les prochains billets, je couvrirai les sujets que j’ai effleurés aujourd’hui et bien d’autres encore, allant de la question des langues à la question raciale en passant par ce que cela fait d’être un Américain – nous sommes très peu ici – vivant en Martinique.

Pour finir, je partage avec vous la réponse à la question posée en introduction. Vous en aurez besoin si vous venez ici : Sa ka maché ! (Je vais bien).