By Dylan Smith – TusconSentinel.com

Reporter and author Charles Bowden — he eschewed the term “journalist” — is

dead. The longtime Southern Arizonan recently moved to New Mexico and focused

his work on the dangerous turmoil of Ciudad Juarez.

Bowden was a dogged investigative reporter and brilliant storyteller with a passion

for the truth. A finalist for a 1984 Pulitzer Prize, he won numerous other awards and

the respect of reporters everywhere with his gritty yet painstaking work.

“People felt that so much of his work dwelt in the dark side and was mired in

negativity. But, he believed in his readers; he believed in people, that change could

happen,” said Mary Martha Miles, a former girlfriend who was Bowden’s companion

and editor for over a decade.

“He thought that people needed to know what was going on, and that change could take place if they did,” said Miles in an interview Monday.

“He thought that people needed to know what was going on, and that change could take place if they did,” said Miles in an interview Monday.

Bowden, born in 1945 and known as “Chuck” to reporters both local and around the world, died during an afternoon nap Saturday at his Las Cruces, N.M., home, family and friends reported.

“It’s a fitting irony that he passed away in his sleep. He took a nap and never woke

up,” said Pima County Supervisor Ray Carroll, noting that Bowden suffered from the lingering effects of a youthful bout with valley fever. “He had a lot of death threats

(because of his work). He had a lot of dangerous liaisons with people in dangerous

places. But he went peacefully.”

Bowden was found around 5:15 p.m. when his girlfriend, Molly Molloy, came home

from work.

Bowden had been ill with congestion that he brushed off as symptoms of the flu,

Molloy said, and had seen doctors twice in the previous weeks.

“I had to work yesterday noon till 5. I called him at 1:30 and he said he was going to

take a shower and lie down,” she said in an email. “I got home at 5:15 and he was in

bed and seemed to be sleeping, but I could not wake him. I called 911 and did CPR

until the police got here.”

“There was nothing we could do. They took him to Albuquerque for an autopsy,” she

said.

Word of Bowden’s death spread quickly through the ranks of reporters and authors.

“He was 69 years old and had been speaking and writing the truth as he saw it for

all of those years,” wrote Utah bookstore owner Ken Sanders. “A lone voice crying

in the wilderness, he was the first American to speak and write about the killings in

Juarez and has been relentlessly writing about the drug trade on both sides of the

border for more than 20 years now.”

“Waking up to a world without Chuck Bowden is devastating. We lost our most

powerful voice yesterday,” tweeted Robert Stieve, editor of Arizona Highways.

Early in Bowden’s career, he was a crime reporter for the Tucson Citizen. He was

one of the founders of the short-lived City Magazine, a circa-1986-89 monthly

journal of politics and civic life in Tucson. He later turned his attention to the

decades-long drug war along the U.S.-Mexico border, and the chaos and death on the

other side of the line.

‘Captured life … a great reporter’

Bowden’s colleagues from the now-closed newspaper spoke of his work Sunday.

“Chuck always kept life real,” said former photo editor P.K. Weis. “He absolutely

captured life around here. This city has never seen a better team of journalists than

Bowden and (Citizen features editor and then City Magazine partner) Dick Vonier.”

“When he got a hold of a story, he wouldn’t let it go,” said former Citizen copy editor

Judy Carlock. “He had a very generous heart and a lot of compassion … he didn’t

mince words.”

“He was compelled to work; he had to write … in vivid imagery and concrete detail,”

Carlock said. “Every Monday morning, the (Citizen) city desk would come in to find a

long, brilliant masterpiece they had to find room for in the paper.”

“He lived at full tilt, fueled on caffeine and nicotine,” said Carlock. Bowden had

stopped smoking about two years ago, Carroll said, and was ‘lifting weights, working

on that second wind in his life.”

“He was no saint, but he was true to himself,” said Carlock. “I think he secretly

relished being thought of as a rogue.”

Bowden was “the most talented storyteller I ever worked with,” said Mark Kimble, a

former Citizen editor.

“He was a really, really good reporter,” Kimble said. “He wrote so well, most people

forget what a great reporter he was — he was a very keen observer.”

Kimble related a story of how Bowden, happening on a group of paramedics

attending to a man who’d had a heart attack. stopped to write some notes. After the

man was taken to the hospital, Bowden picked up a discarded EKG tape that was

sitting at the side of the road. That piece of paper figured into his report the next

day, Kimble said.

“He followed that tape; when the man’s heart stopped, and when it started again,”

Kimble said. “The scene was something that most people would just pass by, and not

give a second thought to.”

“Chuck made it absolutely spell-binding reading.”

Bowden and Vonier “gave me my first real job in the publishing industry back in

1987,” said cartoonist Max Cannon. “Chuck was an intimidating presence to young

me. He was too tall, too serious, too slow and resonant in his speech, and had a kind

of overly patient, scrutinizing demeanor that was unnerving.”

“He lived on his own terms to the extreme — he was a master wordsmith, a

detective, a poet, a scholar, a gentleman rogue, and a fearless traveler into

humanity’s darkest places,” Cannon said Sunday.

“He was both filthy and a pilgrim at the same time,” Cannon said. “He scared the shit

out of me and inspired me at the same time, and I’m not a timid person at all.”

Laura Greenberg, a writer who worked with Bowden on City Magazine, said, “I

would never deify Chuck … he was a crazy motherfucker. He liked the company of

women.”

“He was such a good ‘bad boy.’ I hope people don’t saint him,” she said, describing

him as having compassion for the downtrodden. “If you had a hard-luck story, he

bought it.”

“I loved him,” she said. “He was brilliant and dark and angry.”

The 6’4″ Bowden “was like a gunslinger,” Greenberg said. “He made sure when he

would walk in the room, you would be intimidated by him.”

Always a contrarian, Bowden told Greenberg he hired her because she had “not

been corrupted by journalism school,” she said.

“Charles Bowden was the reason I wanted to be a writer,” said Tucson native Tom

Zoellner, a former Arizona Republic reporter and author of “A Safeway in Arizona”

and other books. “He was uncompromising in his work ethic and his opinions and

the care he put into his sentences. He didn’t let the views of others sway his own,

and he could also be one of the most stubborn ox-legged people I’ve ever talked

with.”

“He was easily one of the best writers working in the English language,” said Miles,

who edited Bowden’s work for 13 years, until they split up in early 2009.

“Chuck was deeply lyrical, with embedded rhythms,” she said. “He pulled people

into and through the most difficult subjects that they otherwise might not have read

about.”

Women & drink

Several friends described Bowden as a long-time heavy drinker, with a fondness for

red wine.

“There was a deep goodness and concern in him, that was completely eroded by the

alcoholism,” said Miles. “He had a deep stubbornness and a strong ego. He’d never

go into a recovery program or seek help.”

“Watching his alcoholism take him down was probably one of the most painful

experiences in the lives of all of the people who loved him,” Miles said.

Bowden was married twice, first in 1968 and then in a marriage that ended in

a 1989 divorce. He had a son, Jesse, in 1987, and a lengthy string of girlfriends,

including a 13-year relationship with Miles and living with Molloy for five years.

What the Phoenix New Times called his “prodigious philandering” two decades ago

may have slowed in pace, but “I didn’t realize the extent of his womanizing” until

after the two split up, Miles said.

“Chuck had been doing really well the last couple years, no smoking, hardly

drinking, eating healthy, exercising all the time, hiking a lot and lifting weights and

writing every day,” Molloy said Sunday.

“Around the first of August (he had been spending time writing in Patagonia, Ariz.)

he came down with what he said was flu. He came back here a few days later,” she

said. Bowden “tried to just rest until I insisted he go to the doctor.”

“His congestion just would not go away,” Molloy said. “He coughed a lot and had

some trouble breathing. The doctor did an EKG and it showed an irregular rhythm

and he was set to go to a cardiologist on Wednesday.”

A test for hantavirus was negative — “… there are a lot of rodents in the place he

was staying in Arizona,” Molloy said.

“Yesterday morning he did seem tired and weak,” she said. When Molloy returned

from an afternoon at work, she found Bowden unresponsive, lying in bed.

“I can picture him up in heaven holding one of those smelly Lucky cigarettes, telling

God how He might run a more just universe and to perhaps add a few more plants.

Down here, his words will continue to resonate and he will be remembered as one

of the most searing and memorable writers of prose ever to come from Arizona,”

said Zoellner.

‘I’m a reporter. I go out and report.’

Bowden moved to Las Cruces about five years ago, where he made a home with

Molloy, a New Mexico State University librarian with whom he collaborated on

border reporting. Molloy established the Frontera List to track the hundreds of

murders each year in Juarez.

“I got messages, threats, delivered two or three times. You never take those

seriously,” he said to I Wanna Know What I Wanna Know in 2012. “The people who

are going to kill you don’t send messages, they send bullets. Those were just efforts

to stop me and scare me.”

While he was living in Tucson with Miles, “we had guns in every single room – he

was careful to never let anyone know where he was,” she said. “The DEA told us

there were three contracts on his life. There was a gun under his desk, even one in

the bathroom.”

Critically acclaimed for his hard-boiled narrative style, Bowden was awarded the

Sidney Hillman Prize in 1996 for the article “While You Were Sleeping,” published in

Harper’s Magazine, and received the PEN First Amendment Award in 2011.

He was a Pulitzer finalist in 1984, while reporting for the Citizen, for his “stories on

illegal immigrants, sexual abuse of children and the deaths of two men.”

Bowden didn’t like to be called a journalist.

“I hate the word,” he told the Arizona Republic in 2010. “It’s a (expletive) gutless

lying word for candy asses. I’m a reporter. I go out and report. I don’t keep a

(expletive) journal … (I) state the truth and give evidence.”

“There are only two kinds of writing, true and false. If writing is true it endures,

even if it’s badly written,” he said.

Bowden spoke of his writing in a 2010 interview with the New Yorker.

“I wrote of murders, tortures, and rapes in a spare manner because a flat tone

conveys agony better than a herd of adjectives,” he said of his book “Murder City,”

about the violence in Juarez.

“The way I was trained up, reporters went toward the story, just as firemen rush

toward the fire. It is a duty. As it happens, I am a coward and would rather write

about a bird or a tree. But, I don’t know how to be aware of such a slaughter and not

report it,” he said.

“I believe that all American writing begins with Lincoln’s second inaugural. The

brevity of adjectives, the direct sparse language, is what modern writing is. It’s

a startling piece of writing,” he told I Wanna Know What I Wanna Know. “And, I

think he helped invent modern writing, as opposed to British writing which will

apparently be paralyzed until the end of time by a love of semi-colons.”

Bowden began his career behind the keyboard as an academic with a University

of Wisconsin-Madison Ph.D. in history. Although he published several books, and

received a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship in 1979, it was his work after a jump

to a newsroom in his mid-30s that left a lasting mark.

“I’ve been struck over the years by how people have attempted to make sense of

me,” said Bowden in a 1993 profile by the Phoenix New Times. “I never thought it

would be very hard to do. I’m pretty plodding and obvious.”

Critics had other takes: The New York Times Book Review called him a “thrillingly

good writer whose grandness of vision is only heightened by the bleak originality

of his voice.” “As a writer seeking justice in his words, he is like a man clearing the

brush, trying to break through, to get enough light and oxygen to see his trees and

sky again before he goes back under,” said the Los Angeles Times.

“He did the most in-depth research that I’ve ever seen. Every paragraph had a book

behind it that he’d read,” Miles said. “He’d go out and report, and then he’d come

home and ruminate.”

“He’d start working around 3:30 or 4 o’clock in the morning,” Miles said. “He said

he would wake up and could see the computer in his mind, see the words that he

should start writing. And then he’d brew the strongest damn coffee you’d ever seen

in your life” and begin typing.

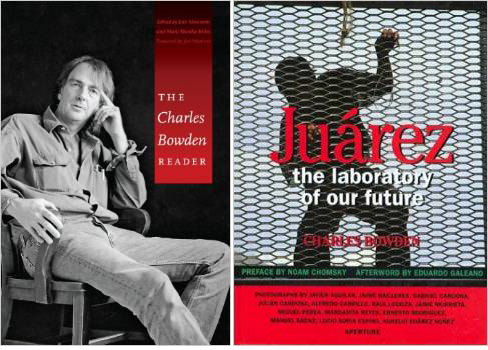

Among Bowden’s two-dozen-odd books were “Murder City: Ciudad Juarez and the

Global Economy’s New Killing Fields” (2010); Dreamland: The Way Out of Juarez”

(2010); “Down by the River: Drugs, Money, Murder, and Family” (2004); “Some

of the Dead Are Still Breathing: Living in the Future” (2009); and “Juarez: The

Laboratory of Our Future” (1998), with an introduction by Noam Chomsky and

Eduardo Galean.

“Dead When I Got Here” is a forthcoming documentary about Juarez inspired by

Bowden’s work.

In addition to his 26 books, Bowden wrote “hundreds and hundreds of magazine

articles,” Miles said, and was a contributing editor for GQ, Harpers, Esquire, and

Mother Jones.

Bowden would attend dinners thrown by GQ and other magazines in New York City,

Miles said.

“When all of the other editors would be getting into their Town Cars afterward,

outside the fancy restaurant, he’d be wearing his jeans and his vest, and one of those

canvas shirts with all of the pockets,” she said. “Even if if was raining, he’d just start

walking down the street back to his hotel.”

“I took a job at a newspaper because I needed money to buy a new racing bicycle.

I walked in and lied, I had no credentials. I thought, if I work here for two or three

months I can buy a bike and get back on the road,” he said in 2012. “I wasn’t there

very long until I had to go write about child murders, and it changed me. I didn’t

leave. I spent three years there because I was learning so much.”

“I got trapped in it because most people won’t cover sex crimes, most people can’t

get people to talk. I was hired to be a fluff writer and I discovered that almost

anyone would tell me anything,” Bowden said.

“He was a kind, warm-hearted man. Not only was he my favorite writer, he was a

close friend,” Carroll said. “We were both kids from Chicago’s South Side, with roots

in the same neighborhood — although he emigrated to Tucson decades before I

did.” (Bowden’s family moved to Tucson in 1957, and he graduated from Tucson

High School.)

“He always tried to aid the Sonoran Desert … he supported many conservation

projects,” said the Republican supervisor.

“He brought stories into the mainstream that otherwise would not have been,” Miles

said. “The women being killed in Juarez, stories of major figures in the cartels, the

fact that there isn’t any water here — he was bringing that up in the ’70s. So often

he was so far out in front of people.”

Bowden, whose early books touched on the S&L scandals and Charles Keating, along

with desert sprawl, was friends with the late author Ed Abbey and often expressed

his appreciation for the desert and those working to preserve it.

“The Center for Biological Diversity has saved more ground than Jesus. I often don’t

agree with them, but their record is better than mine. When I’m dead, and when

everybody reading this is dead, the only thing that matters is ground,” he said in a

2009 interview with the Tucson Weekly.

“You’ve got the desert and the mountains constantly telling you that you have failed

this place—but there’s still time to save yourself,” he said. “Landmarks are an error.

The real landmark is the ground beneath your feet. If you don’t take care of it, it will

kill you.”

Bowden is survived by his girlfriend, Molly Molloy; his son, Jesse Bowden Niwa 26;

sister Margaret “Peg” Bowden; and brother George.

This report was originally published in the Tucson Sentinel Aug. 31, 2014, 11:15 a.m.

His writing brought fear and admiration to me and for him when I thought about what it took to get the story and then have the “ganas” to write it up. I hope many other “reporters” emulate his grit for the story and for life. He was not a journalist who wrote merely to meet the word count.