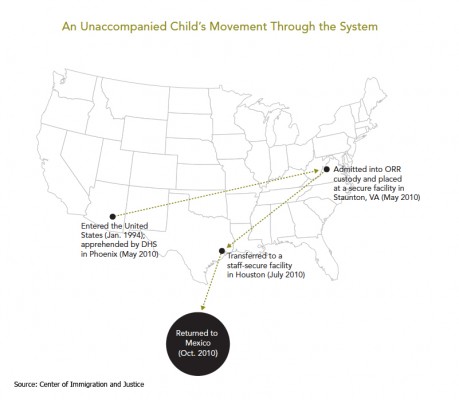

An example of the journey of one unaccompanied child through the system. (Center of Immigration and Justice)

EL PASO – Employees at a children’s shelter in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, found 12-year-old Noemi Alvarez Quillay’s lifeless body hanging from a shower-curtain rod last March. The Ecuadorian girl had been trying to cross the border to reach her parents in New York when police apprehended her.

She is only one of thousands of unaccompanied children braving exhausting heat during the day, freezing winds throughout the night, gang violence and corrupt authorities during their arduous journey north to the U.S. border.

For Alvarez, the perilous journey ended within sight of the bridge that connects the two countries, but for her that was one bridge too far. Mexican authorities ruled her death a suicide because she was in fear of being deported back to Ecuador. The human rights commission of Ciudad Juarez is still investigating the case.

“We see a lot of children who were left behind in the home country so that the parents could come to the United States to work. We have seen cases where the kids come hoping to reunite with the parents without really knowing where they are,” said Melissa M. Lopez, attorney and executive director at Diocesan Migrant & Refugee Services, Inc., which provides legal aid to low-income immigrants and refugees.

These children try to sneak their way into the United States after the long and tiring trip, often atop the open-air rooftop of a train known as “La Bestia” (the beast) that runs from the southern Mexican state of Chiapas all the way north to the border cities of Tijuana, Nogales, Ciudad Juarez, Nuevo Laredo, and Reynosa.

They usually are trying to reunify with family members in the United States or may be fleeing from problems such as poverty, war, violence, or other dangerous circumstances. Frequently on their own, they may have lost contact with an adult along the way.

“We try to find out if there’s been any type of human trafficking they have been subjected to. If they were forced to do anything against their will,” said Lopez.

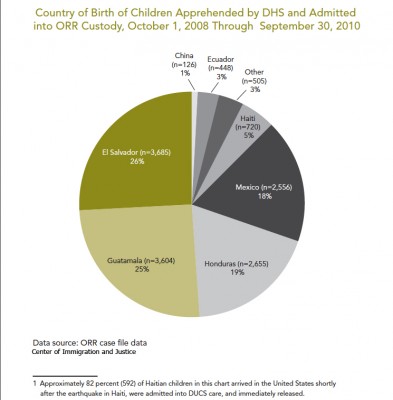

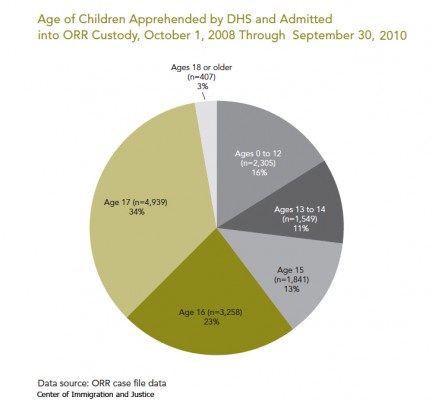

A large majority of them come from Central American countries such as Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador and they generally range in age from 14 to 17, though some like Alvarez are younger.

The Homeland Security Act of 2002 defines an “unaccompanied alien child” as a child who has no lawful immigration status in the United States, is under 18 years of age, and has no parent or legal guardian in the country present or available to provide care and physical custody.

According to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) statistics during fiscal year 2013, the U.S. Border Patrol apprehended 38,833 unaccompanied minors, 28,352 of them in the state of Texas.

Although the number of all apprehensions at the border, including both juveniles and adults, has significantly declined since 2006, the number of unaccompanied children crossing the border has been increasing in recent years. In 2008, a total of 8,041 children traveling alone were detained by CBP, a fairly manageable number compared to the total of 19,668 minors detained in 2009.

“We see a significant number of minors cases, probably a couple of hundred a month at least,” Lopez said. “We try and make the children understand the process that they’re going through, what rights they have, what rights they don’t have, what they can expect from this process.”

Once they are taken into custody by CBP, unaccompanied immigrant children who are not immediately repatriated at the border are transferred to the United States Department of Health and Human Services, specifically to the Office of Refugee Resettlement/Division of Unaccompanied Children Services (ORR)/(DCS)

Country of birth of children apprehended by DHS and admitted into ORR custody. October 1, 2008 through September 30, 2010.

As a matter of statutory obligation, all unaccompanied children who are apprehended by CBP must be turned over to the Office of Refugee Resettlement within 72 hours.

After that point, the children are detained in federal custody in detention centers or shelters contracted by ORR/DCS where they are provided a safe and appropriate environment, as well as care, while their cases are reviewed. ORR/DCS retains them until they are released to a relative or other guardian, repatriated or granted lawful, documented residence in the United States.

The report also states that in fiscal 2009 the Department of Homeland Security admitted a total of 6,092 unaccompanied children to ORR custody after referral. In 2010, this number was 8,207 children, or a 35 percent increase. Between 2008 and 2010, only 1,299 children were released to sponsors in Texas.

According to ORR data, the government projects that 60,000 unaccompanied children will be referred by October 2014 — more than double the 24,668 referrals of 2013.

ORR data also shows a budget increase from $376 million during fiscal year 2013 to $868 million in fiscal year 2014 for the unaccompanied minors program. About $707 million are allocated for shelter expenditures, $45 million for medical expenditures, $90 million for support services and $26 million for administrative expenditures.

ORR says that the average length of stay in the program is currently near 35 days. Of the total number of children served, about 85 percent are reunified with their families.

“Back then INS (Immigration & Naturalization Service, today Homeland Security) had a contract with us. We housed minors 10 to 17 years of age, male and female. I’m thinking they just didn’t know what to do with that particular group (undocumented minors) of people,” said Luis Terrazas, a former shelter employee.

Terrazas worked for a runaway shelter in Dallas, Texas from 2000 through 2002 where he witnessed some of the first efforts by the federal government to find a solution to the growing problem of what to do with unaccompanied minors.

“They weren’t putting children in the same deportation proceeding as the ones that would apply to adults because of other circumstances for them being here, some of them were victims of human trafficking, but we weren’t given all that information. It was very confidential,” said Terrazas.

A large majority of refugee immigrant children have already endured, physical and mental abuse in their home countries and while en route to the United States.

“We were a housing facility providing them with basic necessities, shelter, food, counseling until INS could contact the next-of-kin, which could have been back in the home country or a relative in-country, meaning anywhere in the United States, but that information and those investigations were conducted by INS officials,” said Terrazas.

The massive influx of undocumented children has created a larger need for detention centers and immigrant youth shelters all over the country.

“Our mission is to teach these children as much of the United States as possible, acculturate them if you will,” said a youth-care worker at Casita, a Southwest Key shelter located in Clint, Texas. The youth care worker declined to be identified.

Southwest Key is a national non-profit organization contracted by the federal government to care for and provide services to unaccompanied immigrant minors. As the largest contract facility for unaccompanied minors in the U.S., it operates 17 shelter programs in California, Arizona and Texas.

According to Southwest Key’s website, children are accepted at the shelters anytime of the day or night and trained staff is available 24 hours a day to support them throughout their stay. They receive counseling, medical services, and attend an on-site school while awaiting the resolution of their legal case.

“They stay for about three to four months usually and we try to find their families or sponsors in the United States as quickly as we can,” said the youth care worker. “These kids are workers, they know how to survive. They have a todo o nada mindset, a ‘do or die’ mindset.”

The Office of Refugee Resettlement, which oversees the shelters for unaccompanied minors, did not respond to several requests for permission to interview one of Southwest Key’s directors in El Paso.

Age of children apprehended by DHS and admitted into ORR custody. October 1, 2008 through September 30, 2010. (Center of Immigration and Justice)

Unaccompanied children placed in immigration proceedings in the United States are likely to encounter a complex web of policies and practices, numerous government agencies—each acting in accordance with a different mission and objective—and a legal process that often takes years to resolve.

As these minors cannot be expected to legally fend for themselves, various local legal service organizations provide free or low-cost immigration legal assistance and representation for non-detained children in immigration proceedings.

Lopez’s agency, Diocesan Migrant & Refugee Services, Inc. (DMRS) is the only full-service immigration legal aid clinic to serve low-income immigrants and refugees in the southwestern United States.

DMRS provides free or low-cost direct representation for asylum cases, victims of human trafficking cases (T-visa), victims of crimes (U-visa), for immigrants that are 17 years of age or younger.

“In the cases that we do, the end goal is always that we get the person their residency. Especially with children, we try and stick with the case until the point of ensuring they get residency,” said Lopez.

Great efforts have been made by various agencies and organizations at the local and national level to help reunify immigrant children with their families while providing them with basic services in a positive environment. However, those involved in their care say there is still much more work left to do.

“Our success rate is pretty good overall, probably in the 90 percent to 95 percent range, but that’s not indicative of the whole picture,” Lopez said. “The number of cases that we find where kids are eligible for something versus the number of cases where we don’t find any relief and the child ends up getting deported or returned voluntarily to their country, that number is far larger than the number of kids that we’re able to help.”

We have homeless and starving children in the United States, what are we doing taking in thousands of alien children….send them back to their own countries where they should be taken care of. I am sick and tired of using my tax dollars on illegal aliens, children or adults! I have a 21 year old grandson who can’t get a job because he isn’t bilingual. They don’t tell him that , but we know that is why he isn’t hired. We do not need any more illegals in our country!